The Annotated Nightstand: What Sabrina Orah Mark Is Reading Now and Next

Featuring Daisy Hildyard, Maxine Hong Kingston, Nina McLaughlin and More

As I mentioned in the earlier December post, during the often-dread-inducing/dreadful time of year when publications are putting out there “best of the year” lists, I’m glad to shine a light on a book I loved and think deserves more attention than it seemed to receive. This is always a hard task.

So, aside from this post’s guest, I would have loved to see the to-read piles of these authors and written about their books: Camille Dungy’s Soil: The Story of a Black Mother’s Garden, Etaf Rum’s Evil Eye, Rita Chang-Eppig’s Deep as the Sky, Red as the Sea, Julia Fine’s Maddalena and the Dark, Yume Kitasei’s The Deep Sky, J. Michael Martinez’s Tarta Americana.

The author whose to-read pile we do get to peruse is poet and writer Sabrina Orah Mark. In her book Happily: A Personal History—with Fairy Tales, Mark quotes the folklore scholar Maria Tatar: “Magic happens on the threshold of the forbidden.” This seems to be a guiding principle of the brief essays in the book, which began as a series in the Paris Review of the same title.

In “Happily,” as in the book, Mark attends to motherhood and fairy tales (those two seemingly often-entangled experiences), as well as what Maggie Nelson calls the “unsolvable ethical mess of autobiographical writing.” In Happily’s pages, Mark meditates on the stickiness of writing about family and friends who are potentially hurt by it. About her stepdaughters, her husband’s two ex-wives. When she tells him she’s writing about Bluebeard, his response: “Oh fuck.” The connections between life’s confusions and those of fairy tales seems more and more apt as the book goes on.

In response to reading a fairy tale about a spider and a flea and brewing beer in an egg shell that culminates in scalding, terror, weeping, a flood, Mark writes, “I can’t figure out if this is good news or bad news, and then I remember I am reading a fairy tale, not a will or lab results.” One might say the same thing of a pebble living for months in a child’s ear and, upon its extraction, his saying, “Oh, there you are. I was looking for you all over.”

But the purpose of fairy tales, other than exposing the dark underbelly of how humans think and express what we’re afraid most of is to, ideally, entertain children (but also maybe to terrify them and/or teach them a lesson). Regarding the involvement of her children in this whole enterprise, Mark explains in her interview with David Naimon: “I found myself raising my kids in a place far away from where I came from and suddenly, there’s one school shooting after the next and my kids are Black, and Jewish and I thought, ‘How are we going to all be okay?’ That was the impulse behind the essays, was to remember and to protect…the idea inside of a fairy tale is that the danger comes later, so what happens when you begin in the dangerous place? Can a book protect my kids? Can I turn the essay inside out and wrap it around my kids like some kind of wool, overcoat, bubble, cocoon-type garment?”

She goes on to say that, “If we better understand the world we live in, the things that came before us, and the things that came before that, then before that, will we have better tools to navigate? I think so. Or at least, we’ll have a little bit more light when it gets really, really dark.”

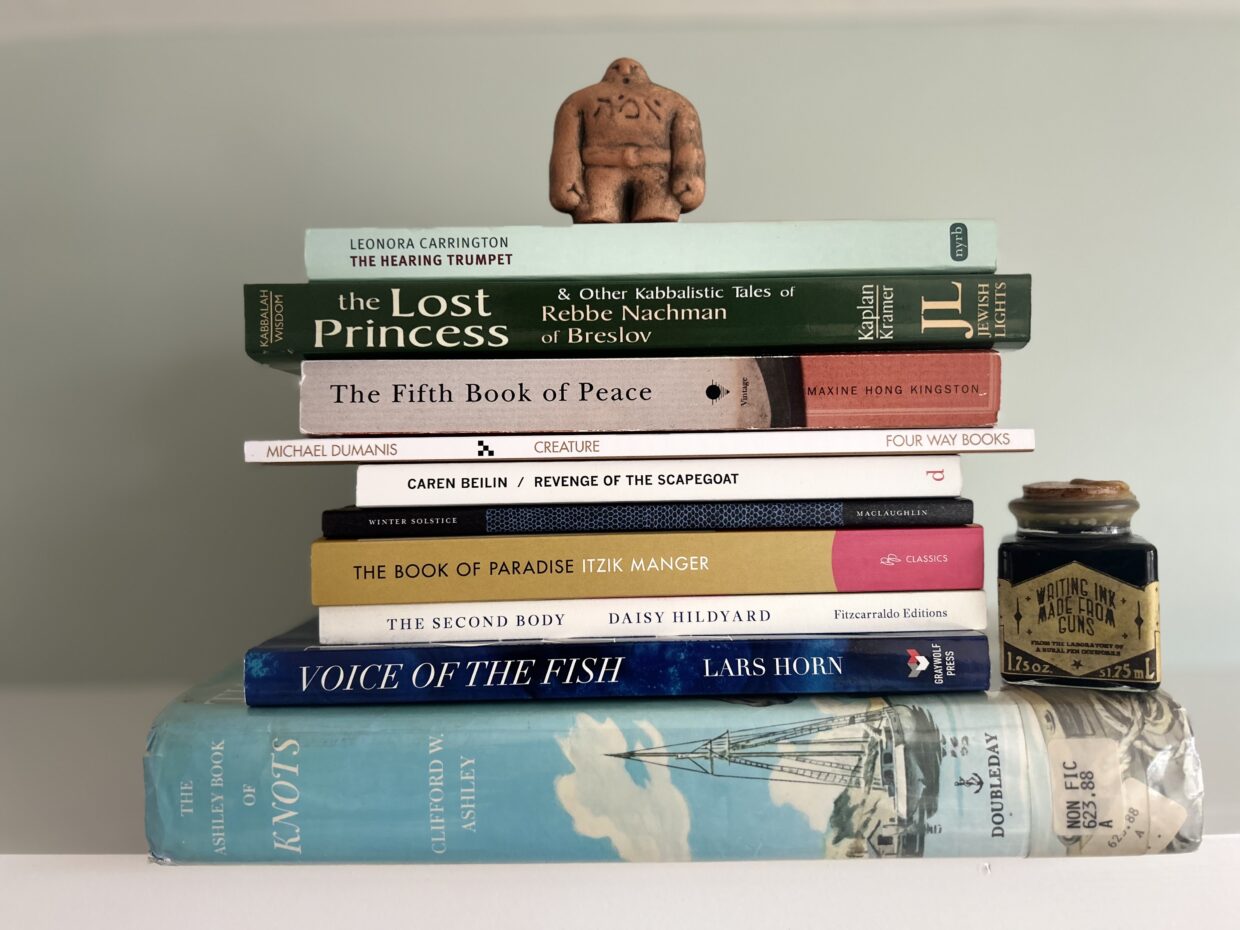

Regarding her to-read pile (note the amazing Writing Ink Made from Guns!), Mark tells us, “My nightstand stack is often more tower than stack, but here is a good representation. Leonora Carrington’s THE HEARING TRUMPET (I’ve read it 100 times) is always at the top to protect the others, and a Golem is always at the tippy top to protect Leonora. My two mystical guards. I have been writing a new book about my house burning down (two winters ago), which is slowly becoming a book about possession and knots and fairy tales and spells and the body and exile and Jewishness. Many of the books on this pile are giving me new ways of thinking about ruin and repair. As Daisy Hildyard writes, ‘What does all this have to do with you? Everything.’”

Leonora Carrington, The Hearing Trumpet

If you do not know of the British-born Mexican creator Leonora Carrington’s art, writing, or tarot cards, may this be an invitation to scope out any (all) of the above. To give a sense of her as a figure, this is how Merve Emre opens her profile of Carrington in the New Yorker: “When asked to describe the circumstances of her birth, the Surrealist painter and writer Leonora Carrington liked to tell people that she had not been born; she had been made. One melancholy day, her mother, bloated by chocolate truffles, oyster purée, and cold pheasant, feeling fat and listless and undesirable, had lain on top of a machine. The machine was a marvellous contraption, designed to extract hundreds of gallons of semen from animals—pigs, cockerels, stallions, urchins, bats, ducks—and, one can imagine, bring its user to the most spectacular orgasm, turning her whole sad, sick being inside out and upside down. From this communion of human, animal, and machine, Leonora was conceived. When she emerged, on April 6, 1917, England shook.”

Rebbe Nachman of Breslov (translated by Aryeh Kaplan), The Lost Princess & Other Kabbalistic Tales of Rebbe Nachman of Breslov

Nachman, an 18th/early 19th-century man born in modern-day Ukraine, was meant to follow the Hasidic tradition and become a leader within the movement (the movement is a hereditary dynastic one, and his grandfather was an important Hasidic figure). Nachman refused—but years later founded the Breslov sect of Hasidic Judaism.

His teachings stated anyone could become a holy person (it wasn’t only delineated by lineage), as well as suggested people sing, clap, and dance while praying. Nachman wrote a series of parables, as in this collected text, many of which are influenced by Eastern European tales. These were to impart stories that connect culture of the area and culture of religion. He died at the age of only 38 from tuberculosis and was buried in Poland. His followers began an annual ritual of visiting his grave on Rosh Hashana, which people did in the thousands. The Russian Revolution made that nearly impossible, and very few attempted to do so while Poland was in the USSR. Only some 70 years later were people able to continue the practice. Roughly 25,000 people went in 2008.

Maxine Hong Kingston, The Fifth Book of Peace

Considering what Mark states about her own work-in-progress regarding losing her home in a fire, it makes sense this book is in her pile. Also, as a writer, can anyone not relate to Kingston’s impulse here? From Publishers Weekly: “In September 1991, Kingston (The Woman Warrior; China Men; etc.) drove toward her Oakland, Calif., home after attending her father’s funeral. The hills were burning; she unwittingly risked her life attempting to rescue her novel-in-progress, The Fourth Book of Peace. Nothing remained of the novel except a block of ash; all that remained of her possessions were intricate twinings of molten glass, blackened jade jewelry and the chimney of what was once home to her and her husband. This work retells the novel-in-progress (an autobiographical tale of Wittman Ah Sing, a poet who flees to Hawaii to evade the Vietnam draft with his white wife and young son); details Kingston’s harrowing trek to find her house amid the ruins; accompanies the author on her quest to discern myths regarding the Chinese Three Lost Books of Peace and, finally, submits Kingston’s remarkable call to veterans of all wars (though Vietnam plays the largest role) to help her convey a literature of peace through their and her writings.”

Michael Dumanis, Creature

Dorothea Lasky says about this collection: “Michael Dumanis’s Creature is the poetry book this year you have to read. Steeped in issues of morality, mortality, plasticity, and existence itself, Dumanis paints a picture of life that is as breathtakingly beautiful as it is terrifying. Just as Dumanis writes, ‘There’s more beyond / but not too much,’ the book asks us over and over again what it means to be a living thing and the answer we are given is not simple or easy to swallow. Each poem’s landscape of perfectly chosen and placed language is a land to wish upon. For just as ‘Everything will be taken away before it’s handed back,’ Creature tells us there is hope after loss, even if it is fractured. There is hope in this book, too, as it speaks: ‘I forget my life, but then I remember my life.’ After all, there is poetry still to write which replaces the silence of death: ‘When I grow up, I do not want to be a headstone./ When I grow up, I want to be a book.’ There’s no doubt that Creature contains the real poetry we have been waiting for for a very long time. Read it and feel your spirit cleansed with the truth of our present and our future—‘we, who are about/ to steer our dinghy/ into the open sea.’”

Caren Beilin, Revenge of the Scapegoat

I know I’ve brought up this podcast already in this post, but in her interview on Between the Covers, Beilin talks about the fact that her estranged father sent her painful letters he had written her in childhood. She explains her rage in response, and how she thought, “‘I will never burn these letters. I will burn them into a novel. This is my revenge.’ I felt full of anger and an incredible tenderness, and all these things, but then my horror was nobody can ever see these letters because if anybody says anything besides that they are horrible, then I will die. It’s such an attachment to what they did to me psychically at that age, that it was very hard for me to imagine sharing them. But I guess, as an artist, that’s one of the things I try to practice, like doing things that are very terrifying. I want there to be stakes in the things that I do and I care about that, so I just knew that was one of the things like, ‘I had to do this terrifying thing’…it was like exposure therapy. It really was. I went from these letters searing into my body, like feeling so tender, I went from that to, I don’t know, just going back and forth over however many emails with Danielle [Dutton editor of Dorothy] being like, ‘Let’s change this word here.’”

Nina McLaughlin, Winter Solstice

This seems like a great book to read as the days get shorter. Heather Treseler in the Los Angeles Review of Books writes, “In her new book, MacLaughlin slides a knife edge under the circadian rhythms of our fall into winter, tracking our inchoate urges—to feast and imbibe; to retreat into cozy hibernacula; to skate, ski, and sled, reveling in the dangers of ice and snow; to press naked skin tenderly against skin; and to ‘honor the dark with festivals of light.’ Drawing on poets and singers from Kobayashi Issa and Emily Dickinson to Will Oldham and Mary Ruefle, MacLaughlin reveals how our responses to the solstice, which means ‘sun-stilled,’ are patterned, ancient, and explicable, related to our deepest fears and yearning for survival.” You can read excerpts of Winter Solstice in the Paris Review.

Itzik Manger (translated by Robert Alder Peckerar), The Book of Paradise

The jacket copy for this recently published translation states, “Witty, playful and slyly profound, this story of a young angel expelled from Paradise is the only novel by one of the great Yiddish writers, which was written just before the outbreak of World War II. As a result of a crafty trick, the expelled angel retains the memory of his previous life when he’s born as a Yiddish-fluent baby mortal on Earth. The humans around him plead for details of that other realm, but the Paradise of his mischievous stories is far from their expectations: a world of drunken angels, lewd patriarchs and the very same divisions and temptations that shape the human world. Published here in a lively new translation by Robert Adler Peckerar, The Book of Paradise is a comic masterpiece from poet-satirist Itzik Manger that irreverently blurs the boundaries between ancient and modern and sacred and profane, where the shtetl is heaven, and heaven is the shtetl.”

Daisy Hildyard, The Second Body

The premise of The Second Body is that all human beings have two bodies,” writes Gavin Francis in The Guardian, “the one they have immediate autonomy over, made of flesh and bone, and another which is more diffuse. Hildyard struggles to define exactly what she means by the second body, but in one place calls it ‘the global presence of the individual body’. Elsewhere it is imagined as an entity shared and distributed across every aspect of the biosphere impacted on by humans.” In the book, Hildyard describes how a flood destroyed her home. Francis goes on, “The flood was part of this second body – an elemental retribution brought about not just by her, but by all the collective bad decisions of Homo sapiens: ‘My second body came to find my first body when the river flooded my house.’”

Lars Horn, Voice of the Fish

I saw Horn read and immediately bought, read, and loved this book. For anyone who loves detailed facts or histories and their potential to connect and make meaning of the moment, it is for you. Corinne Manning writes in the New York Times, “The book’s underlying narrative, layered with histories, myths and vignettes about sea life, is [a] serious injury: In 2014, the author tore the muscles from their right shoulder to their lower back while weight lifting, leaving them unable to speak or read for months — a forced stillness and quiet. They had endured such deathly stillness many times before. Horn was the only child of a single mother, an artist who posed Horn to appear dead for photographs and installations and had them sit for full-body plaster casts. The body always adapts, the book argues. As fluid as gender, as a changing tide, it shifts in response to pressures, which are detailed in vivid accounts here: transmasculine rebirth, transphobic locations in Russia and Florida, violence and injury, and the inevitability of disability. Horn wants ‘language and narrative to carry more physicality.’ ‘Voice of the Fish’ meets this desire with a narrative that swells and recedes, with intimate depictions of the writer’s life as well as more distant tales of Pliny the Elder, a 100-year-old manuscript found in the belly of a codfish, and the history of tattooing.”

Clifford W. Ashley, The Ashley Book of Knots

If you have read and know Moby Dick, you know New Bedford, Mass is one of the most important towns for whaling in the United States. This is where Ashley was born thirty years after that book’s publication. In the early 1900s, Harper’s had Ashley go on a whaling expedition, which he wrote about for the magazine. One of the officers of the boat said of the essays, “The illustrations are so true to life that even the Old Barnacles here cannot find fault with them.” Ashley became a whaling historian and wrote two books on the topic. Ashley worked for over a decade on his book of knots, which includes almost 4,000 knots and roughly 7,000 illustrations. He was the second person to ever receive a patent for a knot of his own making (and he has a couple with their own Wikipedia pages.) While just reading a bit about Ashley and knots, I discovered that “bitter end” is a nautical term for when the end of a rope is tied off—a likely source for the phrase “to the bitter end.”

Diana Arterian

Diana Arterian is the author of the recent poetry collection Agrippina the Younger (Northwestern UP, 2025) and editor and co-translator of Smoke Drifts (World Poetry Books, 2025), a collection of Nadia Anjuman's poetry. A Poetry Editor at Noemi Press, Diana has received fellowships from the Banff Centre, Millay Arts, and Yaddo. She writes “The Annotated Nightstand” column at Lit Hub and lives in Los Angeles.