The Annotated Nightstand: What Olga Ravn is Reading Now and Next

Featuring Ryunosuke Akutagawa, Kate Zambreno, Mikhail Bulgakov, and More

“When Marx wrote that work should be outsourced to machines so the worker could instead write poetry in the morning, who did he imagine changed the diapers?” asks Anna, the protagonist of Olga Ravn’s My Work. This is, in part, the heart of this novel—how to create and also parent? But, also, how to keep sane when you feel yourself splintered into disparate parts after giving birth? As it attends to these and other questions, the book bounces between prose, poetry, play, hospital notes, letter, dialogue, journal entry, essay. It’s largely third-person, but with some first-person. There are chronological leaps. It attempts to describe what explodes form and time: being a new mother. In terms of tone, My Work evokes Sylvia Plath’s poem “Tulips,” which describes a woman in an in-patient facility who has been given a clutch of the flowers. “The tulips are too red in the first place, they hurt me,” Plath writes. “Even through the gift paper I could hear them breathe / Lightly, through their white swaddlings, like an awful baby.” The unsteadiness of the speaker of My Work, as with Plath, along with her laser-focus imagery, gives My Work an undeniable and unsettling power. Just the bald descriptions of the terrifying ups and downs of caring for a baby feel so rare in literature. “I love the way he smells and the drool around his mouth and his pointy little milk teeth,” Ravn writes—but also that there are “days when I feel like taking revenge, when I want to shake and slap him to make him be quiet.” With of this, along with the uncertainty of what was coming next in chronology, form, and Anna’s behavior (would the next scene be tender between her and her partner? Or would she shove him into a wall for telling her she shouldn’t breastfeed?), I found it nearly impossible to put My Work down.

Early on in the novel, we read, “This book began when the child was six days old and I found myself in a darkness…If it weren’t for my handwriting, I might have assumed it was all written by a stranger.” The beginning of the book explicitly throws it into question whether My Work is about Anna or Ravn—or if who we assume is Ravn (the “I” in the book) is actually an unnamed speaker. In any case, Ravn leaves open the possibility she and Anna are one in the same—that the descriptions of Anna’s experiences feel so foreign that Ravn had to give the “I” of that time a different name. At one point, the unnamed speaker tells us, “To write in the third person was to create someone else to endure the pain. One invents her. Her name is Anna.” In its starred review, Kirkus calls the “I,” the person assembling Anna’s papers into a book, a “curatorial presence.” The Kirkus review states, “The fact that the curatorial presence is likely also the author, that Anna herself is an invention created to preserve a necessary distance between the experience of pain and the arrangement of pain into art, does nothing to lessen the intensity of the intimacy created between the reader and Anna.” If this is feels confusing in description, it’s meant to be (though it isn’t as a reading experience). The muddiness of identity and authorship underscores some of the largest concerns of My Work: one’s personhood after becoming a mother and the ways the earliest months of childrearing are so destabilizing. As Kirkus explains, “what is created is an unflinchingly honest reflection of a woman’s experience of her own body as it becomes a body that belongs also to the child.”

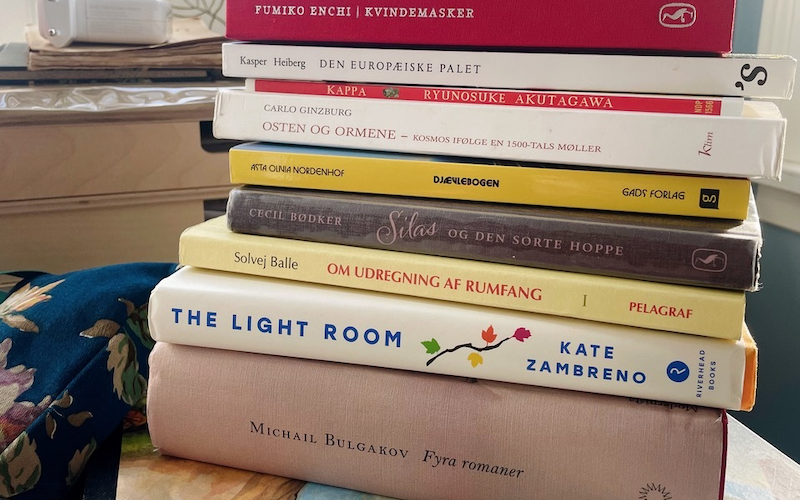

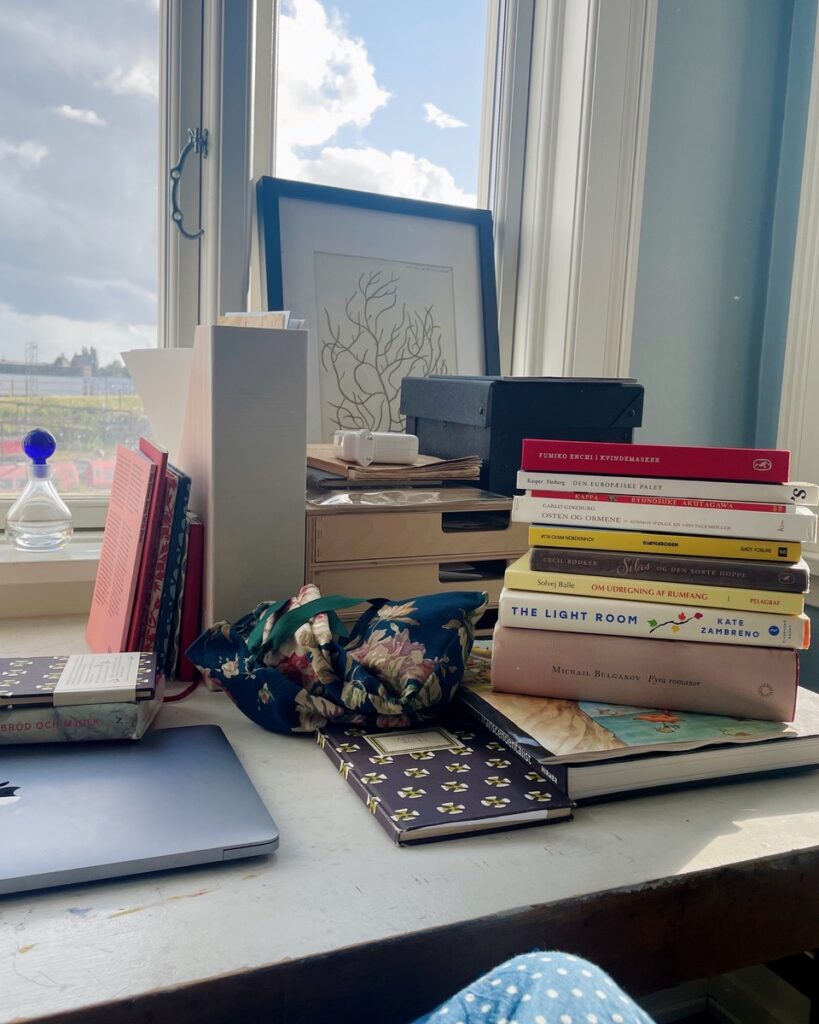

Ravn tells us about her to-read pile, “I am an unfaithful reader, I read several books at once, I rarely finish a book, that doesn’t bother me. If I do finish something it’s usually because I’ll read the book very quickly, and I’ll read with greed, totally consumed.”

Fumiko Enchi, 女面/Kvindemasker (tr. Annette Vilslev)

Fumiko Enchi had a few things that defined her life early on. First, her sickliness—this kept her out of school. Second, her father was a linguist, president of multiple universities in Japan, and made sure she got a stellar education despite her illness (he had her tutored at home). Third, her family clearly had money—to pay for said tutors, among other things. A linguist named Basil Hall Chamberlain, a mentor to Enchi’s father, gifted the family over 11,000 of his books when he left Japan and she was a child, giving Enchi and her family an enormous library. After success as a playwright, Enchi tried to write fiction, but with little success. At this point, terrible life events began to pile on her: cancer, a mastectomy, issues post-operation. During WWII and the horrifying air raids throughout Japan, her home and its contents burned—she lost everything. A year later, she needed a hysterectomy. Are we surprised she stopped writing for a while? It’s amazing she took the pen back up at all. When she did, her novels attended to the war, women, shamanism, eroticism—and received accolade after accolade. This novel, (Masks in English) draws upon The Tale of Genji, which she had translated into modern Japanese years earlier.

Kasper Heiberg, Den Europæiske Palet / The European Pallet

The influential Danish painter’s book is largely a meditation on color in conjunction with his interests. The jacket copy reads, “Republishing of the visual artist, Kasper Heiberg’s book, The European Palette. The book, which was first published in 1972, is a result of Heiberg’s research into color at the Academy of Fine Arts. However, Kasper Heiberg (1928-1984) did not write a work about theoretical color theory, but based on a fascination with the language and world of colors, based on studies of both historical sources and Heiberg’s own contemporaries. In addition to palettes taken from painting and architecture, Heiberg examines, for example, the palette of house sparrows, storks, cars and nail polish.”

Ryunosuke Akutagawa, Kappa (tr. Lisa Hofmann-Kuroda and Allison Markin Powell)

Ryunosuke Akutagawa, the prolific short story writer, has an enormous impact on the Japanese literary world—his name is associated with its most prestigious prize. This novella was published in the last year of Akutagawa’s tragically short life. The Publishers Weekly review of Hofmann-Kuroda and Powell’s translation reads, “Powell and Hofmann-Kuroda offer a crisp translation of this strange, densely literary 1927 fantasy novella from Akutagawa (1892–1927), presented as the account of Psychiatric Patient No. 23. The patient tells an unknown author and a hospital director of his Alice in Wonderland–esque fall down a rabbit hole to Kappa Land, where Kappas—amphibious, thick-billed, webbed-hand and -footed three-foot-tall creatures from Japanese mythology—live in a city that looks ‘exactly like Ginza-dori, one of the main boulevards in Tokyo.’”

Carlo Ginzburg, Il Formaggio e i Vermi: Il Cosmo di un Mugnaio del ‘500 / Osten og Ormene: Kosmos Ifølge en 1500-Tals Møller (tr. Ole Jorn)

Okay, this may win the best title I’ve seen in a while. The English translation: The Cheese and the Worms: The Cosmos According to a 16th-Century Miller. Even just scraping the very top of the Wikipedia page on this text I’m learning new genres of history—in this case “microhistory” (aka “ask large questions in small places”). Ginzburg’s 1976 historical inquiry regards the miller Menocchio, a literate peasant, who spoke freely about his ideas regarding the world and religion. A tough time to do that if you didn’t toe the line. He didn’t, didn’t think he was doing anything wrong, even—so he had a loose tongue when he was questioned by the Roman Inquisition. Ginzburg gets his title from one of Menocchio’s statements to the Inquisition: “[I]n my opinion, all was chaos, that is, earth, air, water, and fire were mixed together; and out of that bulk a mass formed—just as cheese is made out of milk—and worms appeared in it, and these were the angels.” He also said blasphemy only injured the blasphemer, Mary wasn’t a virgin, the Pope doesn’t hold divine power. His fate was sealed pretty quickly.

Asta Olivia Nordenhof, Djævlebogen

This is the second novel in a series by Nordenhof that focuses on the actual fire on the passenger ferry the Scandinavian Star in 1990—a tragedy that killed 159 people. A convicted arsonist was on board and died, so investigators considered it a closed case (though some specialists contest this determination). While not available in English, its title is The Devil’s Book in translation. The jacket copy reads (via Google translate, apologies): “A grand literary project about money, violence and love. The Devil’s Book is an attempt to answer the question of whether it is possible to love under capitalism. The novel takes us on a journey with businessmen and the devil, who lures, not just with money and sex, but also with the prospect of an iconic death. We will also take a trip to the madhouse to see which devils are hiding in there. Not least we must see if it is possible to write love poetry. Whether we can step out of loneliness and into the new world, which may already be here.”

Cecil Bødker, Silas og den Sorte Hoppe

This is the first in a series of young adult fiction by Bødker, a Danish writer and poet who won several awards in her lifetime, largely for children’s literature. This book (Silas and the Black Mare in English) was published in 1967—and Danish readers followed Silas up until 2001! Silas is a thirteen-year-old boy who is forced by his mother to work at a circus until he runs away, managing to take his beloved horse with him. In the description of Bødker by the Hans Christian Andersen Awards, they state about the Silas books, “The first book of the series appeared at the time when Astrid Lindgren’s Pippi Longstocking had become a cult figure of the anti-authoritarian revolution taking place in education and in relation to children. The integrity of children and their right to live life on their own terms became important goals in their upbringing…This historical development is reflected in the Silas series.”

Solvej Balle, Om Udregning af Rumfang

This seven-part book series that blew up in Denmark largely by fans telling others to read it. The jacket copy reads, “What would you do if the same day repeated itself over and over again and you were the only person to experience it? This is what happens to Tara Selter, the protagonist in On Calculation of Volume, a novel series about love, existential loneliness and finding meaning in the everyday. Written with intense clarity and precision, we follow Tara in volume I as she attempts to find a way back into time with the help of her husband who remains blissfully unaware of the day’s repetition.” Balle’s book was recently acquired by Faber and will be translated into English by Barbara J. Haveland as On Calculation of Volume.

Kate Zambreno, The Light Room: On Art and Care

“We find ourselves in the age of Covid literature. The publishing cycle, notoriously long, has caught up with the pandemic, and a book on the subject no longer seems like a novelty,” writes Eleanor Henderson in her New York Times review, of Zambreno’s new memoir, “This is a book about the aloneness of motherhood — the limits of maternal attention, the dissolution of self, the mind-numbing tedium of raising small children — as much as it is about the pandemic. It’s a book about a “life inside” — not just inside the home, but inside the mind. Zambreno’s writing is sharpest, most emotionally alive, when it drills into that interior landscape. Sitting on a park bench with her infant in the winter, she writes, “I briefly allow myself a spasm of feeling miserable and contained. Allowing myself that self-pity feels close to freedom.”

Mikhail Bulgakov, Fyra Romaner (tr. Lars Erik Blomqvist)

This is a collection of four novels by Bulgakov (English translation of the title says as much). Ravn explains, “I’m reading The White Guard.” And it makes sense why she would—the novel is set in Ukraine, likely Kyev, early on during the Ukrainian War of Independence in 1918. Four armies clash in the city, creating mayhem and devastation. An intellectual family, the Turbins, finds itself caught up in the chaos. The Turbin family members are generally lifted from Bulgakov’s life—to the point where damning plot twists seemed to implicate a brother-in-law and created a rift in the family. Some (including one based on Bulgakov’s brother and Bulgakov himself) remain loyal to the White Army—those fighting the Bolsheviks. A play version of the novel was a huge success, despite the fact it portrayed officers of the White Army with dimension and humanity (rather than the propaganda and what the government largely allowed). Eventually the Soviet government pressured the theater to stop the production, which it did—until Stalin himself, wildly, intervened. Apparently, he loved the play and saw it fifteen times! The show ran for ten years, and did almost a thousand performances.

________________________

Olga Ravn’s My Work, translated by Sophia Hersi Smith and Jennifer Russell, is available now from New Directions.

Diana Arterian

Diana Arterian is the author of the recent poetry collection Agrippina the Younger (Northwestern UP, 2025) and editor and co-translator of Smoke Drifts (World Poetry Books, 2025), a collection of Nadia Anjuman's poetry. A Poetry Editor at Noemi Press, Diana has received fellowships from the Banff Centre, Millay Arts, and Yaddo. She writes “The Annotated Nightstand” column at Lit Hub and lives in Los Angeles.