The Annotated Nightstand: What Morgan Talty Is Reading Now, and Next

Featuring Anton Chekhov, Nick Rees Gardner, Joseph Osmundson, Others

Before Morgan Talty’s novel begins, he opens with a brief letter to the reader in which he describes how he and friends, as kids, talked about “how much” Penobscot they were. “Blood quantum is a colonial tool that many federally recognized tribes use to keep track of citizenship,” Talty writes. “This was before we knew these men, the so-called white Fathers, had plans intended for us to eat each other’s spirit piece by piece.”

The chafing speck at the center of Fire Exit that precipitates the story is indeed about blood quantum—for the protagonist Charlie’s daughter doesn’t know she is biologically his. If he were on his daughter’s birth certificate, her “percentage” would be too low for her to claim tribal rights, as Charlie is white. “This is for the baby, you have to understand that,” his Penobscot girlfriend tells him as she leaves him.

But that’s all in the past. Now we’re in a present in which his daughter is an adult, raised by his ex-girlfriend and a man from the tribe who has been a loving parent. Charlie knows—he has watched their home for years from his house just outside the reservation, where he was forced to leave at the age of 18, having no blood rights to stay. Charlie’s primary focus in the novel is to reveal, finally, to daughter Elizabeth that he is her biological father.

Charlie was raised by his white mother Louise and Penobscot stepfather, Frederick, whom he felt was his own. At one point Charlie states, “It was Frederick’s love that made me feel Native. He loved me so much that I was, and still am, convinced that I was from him, part of him, part of what he was part of.” Considering his own nuanced and complicated relationship with parenthood, it begs the question: why tell Elizabeth at all? He meditates, too, on blood, saying, “Blood matters only enough to keep us alive.”

Largely Fire Exit reads as an indictment of a system of measurement created, as Talty notes in his opening letter, by people bent explicitly toward destroying Indigenous communities in the Americas and yet those same surviving communities feel compelled to employ. Charlie rejects the entire premise, instead explaining, “All I wanted was that [Elizabeth] know the history that was hers, that this history wasn’t lost or wasted because of the illusion we’d tried to live in so neatly.”

The messy reality of life Fire Exit documents is in the responsibility we have for one another: to parents (blood or not), children (blood or not), and friends (blood or not) that create a sense of love and kinship. There is the powerful thread involving Charlie’s care for his mother Louise, after years of distance, during her decline due to dementia. Or his friend from AA who gets drunk every night and Charlie consistently bails out of his shenanigans—and who helps Charlie so much and often, too.

In her starred review in Booklist, Margaret Quamme states, “A wrenching story of dislocation and regret, sweetened with touches of humor, the novel raises important questions about human connection and belonging.”

On his to-read pile, Talty tells us, “I’m a re-reader, reminding myself of my roots and my early teachers, and so I like to dig in and out of texts marked with ink from years back. When I find new books to read and my old books are back on the shelf, I know I’ll return again to them in some years and find them to be older and wiser still.”

*

Anton Chekhov, Forty Stories (trans. Robert Payne)

Chekhov’s mother was a storyteller and loved by her children. His father was an abusive tyrant who landed the family in financial dire straits, fleeing to Moscow to avoid debtor’s prison. Chekov stayed behind, sold the family possessions, and paid for his education through tutoring and capturing and selling goldfinches. Eventually he wrote to pay for his schooling.

The trying circumstances of his childhood seemed to drive much of his adult life, as when he gave a brother a verbal thrashing for his own abuse of his family: “[R]ecall that it was despotism and lying that ruined your mother’s youth. Despotism and lying so mutilated our childhood.”

When Chekhov became a physician, he treated the poor for nothing. He was deeply motivated to see and document the abuses at labor camps and argued for prison reform. All while writing some of the world’s greatest short stories and plays and slowly dying of tuberculosis, to which he would ultimately succumb at the young age of forty-four.

Months before he died, Chekhov told a friend people would read his work for seven more years. “Well, seven and a half. That’s not bad. I’ve got six years to live.”

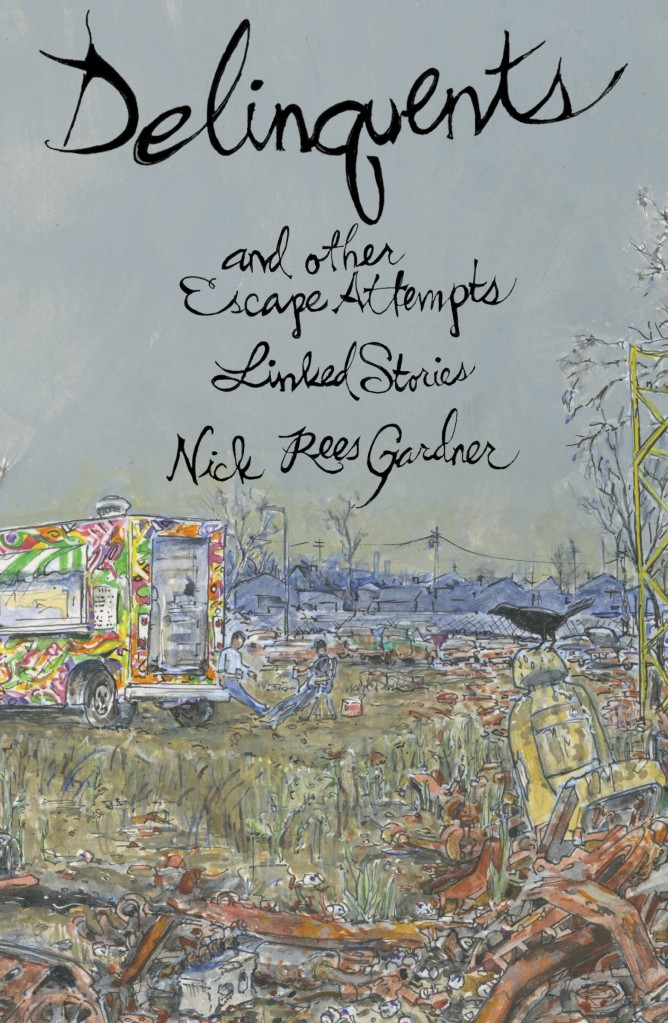

Nick Rees Gardner, Delinquents and Other Escape Attempts: Linked Stories

This book isn’t out for a while, so not much of an internet e-paper trail (sorry) yet. Here’s the jacket copy:

When you’re trapped in a Rust Belt town, time passes or it doesn’t. The people of Westinghouse, Ohio know this better than most. In Delinquents, their personal worlds expand and collapse in on themselves as they battle addictions, build scrap-metal rocket ships, and tether themselves to plans that will either get them out of dodge or blow up in their faces. A former Deadhead seeks sobriety in his hometown, though his decades-old childhood trauma has been exhumed and now awaits him. A sometimes-recovering addict asks his younger sister to put him up as he repairs cars in their yard and she scrabbles to keep her own sanity….Nick Rees Gardner’s linked stories portray people as they are: alternately hilarious, desperate, resilient, broken. For the characters contained in Delinquents, the crux is determining which they’ll be when the music stops.

Ben Shattuck, The History of Sound: Stories

In its starred review, Kirkus describes Shattuck’s collection as

A dozen paired stories, thematically unified across decades and centuries. Echoing a song form popular in 18th-century New England, the second story in each pair deepens and clarifies the first. A painting of a bird left as a parting gift in 1796 (“Edwin Chase of Nantucket”) turns up in a widow’s attic more than two hundred years later (“The Silver Clip”), yet in both it is a token of regret and loss. The Massachusetts apple orchard where Hope abandoned her baby in 1881 (“Graft”) has been reduced by the twenty-first century to “a few grizzly old apple trees” on a property owned by a couple desperate to help their son, lost to drug addiction (“Tundra Swan”)…Shattuck writes with delicacy and restraint of the uncertainties, missed signals, and mixed feelings that trouble personal relationships across the centuries even as we yearn for love and meaning. Intricately structured, powerfully emotional, beautifully written: This is as good as short fiction gets.

Joseph Osmundson, Virology: Essays for the Living, the Dead, and the Small Things In Between

Osmundson’s collection was an NBCC Award Finalist in Nonfiction and named here at Lit Hub one of the most anticipated in 2022 (when it came out). Judith Butler writes in their blurb for Osmundson’s book,

Virology is a brilliant book, both playful and serious, showing us all how viruses live with us, as we live with them. Drawing on queer theory, Osmundson offers a way of understanding care in the midst of anguish and anxiety as well as desire and hope. The viral world is the ordinary world of life and death, of caring for one another in our vulnerability and persistence. This book explains the science of virology for our times, offering a compassionate education for all of us disoriented in pandemic times. This book is queer pedagogy at its best: non-patronizing, thoroughly smart, and full of urgent and caring knowledge that beckons us to get closer again with caution and passion.

James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time

James Baldwin’s writing, no matter how frequently or deeply I read it, feels evergreen in its urgency and devotion to humanity. As an example, “A Letter to My Nephew,” part of The Fire Next Time, Baldwin writes, “Please try to remember that what they believe, as well as what they do and cause you to endure does not testify to your inferiority but to their inhumanity.”

For many other powerful statements, if you’ve got an hour to spare and want to watch him trounce William F. Buckley, you’re welcome. Baldwin’s stepfather was, as made clear in the semiautobiographical Go Tell It on the Mountain, a difficult parent who harbored animosity toward Baldwin. The fact he wasn’t Baldwin’s biological father was kept a secret, a revelation which Baldwin overheard when he was a child.

Baldwin’s mother had eight children with her husband—the last of whom was born the same day her husband died of tuberculosis. The funeral was on Baldwin’s nineteenth birthday, when the 1943 Harlem uprising broke out (where Baldwin and his family lived). It must have been a wild and trying time for the family. The writer and curator Ikechúkwú Onyewuenyi blessed us all by creating a playlist of all the records in Baldwin’s Saint-Paul-de-Vence home (which even his landlord called “Chez Baldwin”).

Paul Tremblay, Horror Movie: A Novel

Tremblay’s Horror Movie chronicles a low-budget-cum-cult-hit horror flick from the 1990s is getting (you guessed it) rebooted with its one surviving actor. Lila Denning in a starred review at Library Journal writes,

As the novel’s protagonist becomes more involved with the remake, secrets buried in the past start to resurface, including details of strange events during the original filming and the tragedy that occurred on set. Narrated with a sardonic tone and Gen-X sensibility, Tremblay’s (The Beast You Are) novel shifts between the filming of the original movie and of the present-day remake, sprinkled with excerpts from the films’ scripts. Unease and terror rapidly build in the book as readers learn details of what happened on the original set and how it threatens the present. The novel is as unsettling and gripping as a slasher while also managing to be funny and thoughtful.

The VERDICT? “Balancing a terrifying cursed film with examinations of artistic creation, fandom, and truth, Tremblay’s latest is smart and well-paced and will have broad appeal.”

Robert Browning, Selected Poems

Well, if any other poets want to feel as badly as I do right now, here’s a fun Browning tidbit: he wrote his first book of poems at the age of twelve. Want to feel worse? He destroyed it! Why? No publisher (in case you need to be reminded of his beautiful emo spirit).

Browning is famously half of the power couple with Elizabeth Barrett, whom he wrote as he loved her poems. (She was far more famous than he and was apparently even on the shortlist to be Poet Laureate after Wordsworth died—it went to Tennyson.) Barrett was a “semi-invalid” writer whose father said he would disown her if she ever got married.

She and Browning wrote increasingly romantic letters and eloped and went to Italy. Their marriage was apparently a wonderful one, and they had enormous influences on each other’s work. A few months before Browning died in 1890, his friend recorded him reciting a bit of “How They Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix.” The cylinder recording was played on the anniversary of his death, apparently the first time someone’s voice was heard after they died.

Michel de Montaigne, The Complete Essays (trans. M. A. Screech)

Montaigne began writing his essays in his thirties after a series of life-changing experiences: he had become a lord and inherited his family estate, suffered a near-death horse-riding accident with a long recovery, and lost an infant child. On this birthday (!), he shut himself up in the tower of his chateau with fifteen hundred books to write. It would be about a decade before the essays were done.

Montaigne had an inscription, originally in Latin, on his bookshelf:

In the year of Christ 1571, at the age of thirty-eight, on the last day of February, his birthday, Michael de Montaigne, long weary of the servitude of the court and of public employments, while still entire, retired to the bosom of the learned virgins, where in calm and freedom from all cares he will spend what little remains of his life, now more than half run out. If the fates permit, he will complete this abode, this sweet ancestral retreat; and he has consecrated it to his freedom, tranquility, and leisure.

TLDR: he had a midlife crisis. I suppose there are worse things than shutting yourself up with over a thousand books and essentially putting a form of writing on the literary map.

Venki Ramakrishnan, Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for Immortality

Ramakrishnan won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2009 “for studies of the structure and function of the ribosome.” Annoyingly (I say this with love), he seems to also be a knockout writer.

In its starred review of Why We Die, Publishers Weekly states,

Discussing the molecular processes that contribute to aging, [Ramakrishnan] explains that the ends of chromosomes feature repeated genetic sequences, some of which are lost every time a cell divides until the replicated sequences have been exhausted. At that point, the cell stops dividing, reducing the body’s capacity to regenerate tissue….The author has a knack for making biology accessible (“You can think of damage to mitochondria from oxidation as a case of our cells rusting from within”), and he brings a searching philosophical sensibility when considering the wisdom of seeking to extend life, cautioning that ‘a greatly extended life span would deprive our lives of urgency and meaning, a desire to make each day count.