The Annotated Nightstand: What Mai Nguyen Is Reading Now and Next

A Series by Diana Arterian

In a note preceding her new novel Sunshine Nails, Mai Nguyen explains that she had wanted to write a book about nail salons for some time. Ultimately she was inspired by the New York Times’ publication of “The Price of Nails”—an investigative article that illustrated the exploitation that took place at some salons of their workers. With this article, Nguyen explains, “the story came to me: a Vietnamese family struggling to keep their no-frills salon afloat in this era of exploitation, rapid gentrification, and chain store proliferation.”

This is made manifest through the Tran family, who each get close third-person chapters in rotation: a mother, father, adult daughter, adult son, and distant cousin who has recently immigrated to Toronto. Tuyết/Debbie and Xuân/Phil Tran came to Toronto after the American-Vietnam War and soon set up Sunshine Nails. Their hard work allowed for their children, Jessica and Dustin, to reach successes of their own as adults. But Jessica’s life has imploded, Dustin can’t get a raise he deserves (or a girlfriend). Their cousin Thuy recently immigrated from Vietnam in hopes to become a nurse but, because of lack of funds, is earning her keep as the star nail artist of the salon.

Early on in the novel, the matriarch Debbie “thought about all the times she felt wronged in her life. There were too many to count.” This could apply to all the Tran family we meet, who have been wounded in ways (largely, wildly—or by a thousand small cuts). When news hits a sleek branch of a NYC nail salon chain is set to move in across the street from Sunshine, the uneasy but manageable holding pattern they had is under undeniable attack.

The events that follow, Publishers Weekly states, will “[prompt] readers to wonder how far the Trans will go to hold on to their legacy and whether they’ll tarnish it in the process. Nguyen imbues her characters with humanity and nuance, making hay from all their imperfections. Readers are in for a treat.”

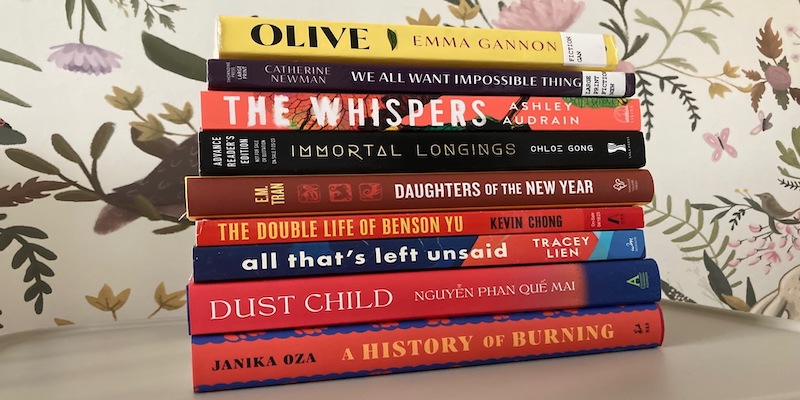

Nguyen tells us about her pile, “My TBR pile mostly consists of Asian-American and Asian-Canadian authors. Growing up there was such a dearth to choose from. Now I can’t keep up. I’m also currently obsessed with books about friendship and motherhood, which are themes in the book I’m working on. You’ll notice that library books go on the top of my pile—that’s because I need to read and return them asap!”

*

Emma Gannon, Olive

The podcaster and author of Ctrl Alt Delete: How I Grew Up Online moves into fiction with her first novel Olive. The protagonist’s long-term relationship ended over Olive’s desire not to have children.

On BBC Radio, Gannon explains, “I’ve really felt the momentum of the ‘child-free by choice’ conversation. A lot of younger women in their 20s are getting in touch [about the book] saying, ‘I feel so relieved, I’ve always felt this way.’ But also older women who feel really unapologetic and really happy with their life choices, but have always felt the stigma of society and their family members. You’d think we would have gone past this, and I am getting some comments saying, ‘wow, we’re still talking about this?.'”

Catherine Newman, We All Want Impossible Things

Julie Klam’s review of We All Want Impossible Things in the New York Times pins down this book well. Klam writes, “There is a type of book that I like to refer to as ‘really too sad for my taste, but so good I couldn’t put it down, and now I have to tell everyone I know they have to read it.’…Here is the thing about this book. It is excruciatingly heartbreaking, but I laughed out loud on almost every page. And I am not an easy laugher. Newman’s voice is hilarious and warm; her characters feel like old friends. About oversubscribed facilities, she writes: ‘Wait list? Do they understand the premise of hospice?’ We pictured an intake coordinator making endless calls, crossing name after name off her list. ‘Yes, yes. I see. Maybe next time!'”

Ashley Audrain, The Whispers

The Kirkus Review response to The Whispers explains the logistics of Audrain’s whodunit. They write,

Women don’t stand a chance in Audrain’s pessimistic suspense novel concerning a child’s mysterious fall from his bedroom window. Ten-year-old Xavier lies in a coma from which he may not recover. His mother, Whitney, sits silently distraught by his hospital bedside. Months earlier, at a garden party Whitney hosted for her neighbors, guests overheard her berating Xavier through the same open window he’s fallen from. Emergency room doctor Rebecca lives across the street, in a gentrified neighborhood of an unnamed city, and was at that party with her husband. Now Rebecca can’t help asking herself the obvious question: Was it an accident, or did Xavier jump, or was Whitney somehow responsible? As other women from the block come into focus, it becomes clear that Whitney is not the only woman with guilty secrets.

Chloe Gong, Immortal Longings

This is a book I’ve been meaning to snatch up for my own summer reading. Gong is a kind of wunderkind who started writing roughly a novel a year when she was 13. Her first YA book, These Violent Delights, in college, which became a New York Times bestseller. The thing that draws me to Gong (other than writer wonder/jealousy, of course), is that her books often are connected to literary dramas we likely know: those of Shakespeare. These Violent Delights engaged with Romeo and Juliet, set in Shanghai.

Immortal Longings considers the events of Anthony and Cleopatra in Kowloon Walled City. In its starred review, Publishers Weekly states, “Though this outing owes debts to both Shakespeare and The Hunger Games, the intricate magic system feels entirely fresh. Gong keeps the pages flying with pulse-pounding action, tension, and intrigue, creating an adventure that will linger in readers’ minds long after the last page.” You can read an excerpt in Cosmo, too.

E.M. Tran, Daughters of the New Year

A “favorite book” for Salon in 2022, Alison Stine writes there, “The only thing better than a good story might be multiple stories in one. Beautiful and heartbreaking, Daughters of the New Year is a tale of survival, focused on the women in a Vietnamese immigrant family. The novel moves backward through time, starting with the present-day in New Orleans and reaching back to wartime Vietnam, French colonial rule and even 40 A.D. Each leap is rich with strong, warrior women. The story-within-a-story format of E.M. Tran’s debut novel, which the New York Times called ‘daring,’ helps readers better to understand generational trauma, family and the heavy legacy of time. It’s also a gorgeous, transporting read.”

Kevin Chong, The Double Life of Benson Yu

I have to hand it to Lorraine Berry and the LA Times for this title: “Trauma plot, meet samurai lizard: Kevin Chong on his mind-bending, Chinatown-set novel.” Berry describes the titular character of The Double Life of Benson Yu thusly, “Benson’s childhood was spent in an unspecified Chinatown in the 1980s, living with his grandmother after his mother died. All he knows of his father is that he’s some kind of ‘bad man.’…What begins as realist fiction pivots with a gigantic metaphysical twist, asking big questions about what obligations a writer has to their characters.”

In the interview, Chong states, “If you’re confronted by somebody who has taken something from you, done something terrible, maybe you’re not in a position to write about it in a way that’s level-headed, that allows for ambiguity. That’s something Benson is trying to figure out, or is learning over the course of the story. The problem is it’s something huge in your life that inspires the writing. Benson’s approach creates a sort of false binary. Either he doesn’t write about it or he idealizes it.”

Tracey Lien, All That’s Left Unsaid

Tuan Phan reviews All That’s Left Unsaid for Diasporic Vietnamese Artists. In his review he writes:

The novel is set in Cabramatta in the 1990s, the “Little Saigon” of Sydney, during the height of the suburb’s heroin epidemic. The sudden brutal killing of a high-achieving Vietnamese high school senior nearly on his way to fulfilling his parents’ dreams is met not with outrage from the community, but a disconcerting silence instead… The book’s greatest strength is its richly drawn and diverse cast of minor characters, many of whom take turns briefly narrating the story. The well-intentioned, caring, but ultimately ineffective white school teacher, the Vietnamese drug dealer that’s also a gifted student, the auntie wedding singer who yearns for her childhood home in Saigon, are all portrayed with complexity and all given a momentary spotlight to share their reasons for remaining silent. Their presence adds depth to the sense of loss felt in the community and heightens the frustration at Cabramatta’s missed opportunities for redemption and resolution.

Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai, Dust Child

Dust Child draws its title from what a biracial child born after the American-Vietnam War is called: “the dust of life.” Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai’s novel circles around the often heartbreaking circumstances children with Vietnamese mothers and American soldier fathers endured in the aftermath of American brutality.

Mai states in an interview at NPR,

As a person who moved from North Vietnam to South Vietnam, I felt like a refugee. You know, people from the North, like my family, were resented, and I was bullied. So I felt such compassion towards Amerasian children, who were also bullied, around me. But I didn’t dare to speak up. For years, I was wondering what happened to them. So when I researched about this novel, I was shocked to see the extent of the discrimination that they faced, and I was very much inspired to see their courage and, you know, their struggles over time. And in this book, you know, I want to present Phong, a Black Amerasian, not as a victim.

Janika Oza, A History of Burning

Oza’s debut novel follows a family over a century through a series of migrations and struggles from the late 1800s in India to Uganda to Canada, culminating in the Rodney King uprisings in Toronto in 1992. Oza states in an interview at Electric Lit:

[W]hen I was thinking through these questions of complicity and resistance, I came up against questions of security and belonging: Who gets to feel safety and security in these countries? What does it mean for us to find refuge in a place that is also causing harm to other communities? What does safety mean in that context? ….Something else that was really important to me in the novel was being able to see the movements of, not only this family, these people, but of the movements through the generations of ideas, emotions, of trauma, of memory, all of that making their way through the earliest generation into the final generation in Toronto.

Diana Arterian

Diana Arterian is the author of the recent poetry collection Agrippina the Younger (Northwestern UP, 2025) and editor and co-translator of Smoke Drifts (World Poetry Books, 2025), a collection of Nadia Anjuman's poetry. A Poetry Editor at Noemi Press, Diana has received fellowships from the Banff Centre, Millay Arts, and Yaddo. She writes “The Annotated Nightstand” column at Lit Hub and lives in Los Angeles.