The Annotated Nightstand: What Kelly Link is Reading Now and Next

“There are far too many good books in the world... But that’s a good thing, right?”

Laura, Mo, Daniel, and a flighty outsider who has named themself Bowie have all returned from something, we glean, is akin to hell. They are filthy and look like they’ve clawed themselves out of their graves. The unassuming “You Are Magic”-shirt-wearing music teacher has a powerful otherworldly capacity—it is he who reconstitutes them into their bodily forms, gives them hints at how to survive.

With the wave of his finger, he convinces the whole town the kids didn’t go missing but were studying abroad in Ireland. A few other supernatural figures from the beyond descend on the sleepy New England town of Lovesend—and who all seem to have plans for these people who have, somehow, come back from the dead.

The teenagers remember nothing of how they died, or how they got back. Within an hour of being alive again, however, they do learn 2 return 2 remain, that there’s some sort of game—and that they no clue how to win it. In addition to Laura, Daniel, and Mo as central characters, we have Laura’s sister, Susannah, a young woman left adrift by her sister’s disappearance who, without the memory of that loss, is just adrift.

There’s a person named Thomas tethered to a powerful woman who has no sympathy for humans and wears knife-sharp pointed toe boots. The people who have returned are all remarkably young and they are dealing with ancient or ageless beings with remarkable magical powers—the odds are clearly stacked against them.

In fits and starts, the resurrected teens learn a detail, a hint about the central mystery of how they disappeared, where they went, and how they got back. At times the reader pieces things together just a beat or two ahead of the those three—but often the revelations come to us at the same time as the cohort trying to figure out how, exactly, to stay alive.

While Link remains in third person throughout the book, each chapter focuses on one character. These are snappy and brief, the cliffhangers palpable—it’s hard to put the book down. While there is magic and sex and music and tigers in The Book of Love, the most significant matter for these characters is as the title suggests: the love and relationships of many shapes (siblings, friends, hookups, parents, exes). Link gives the yearning for connection that so often defines the years of young adulthood room to breathe in a way we rarely see.

While this is a novel of many vibrant fibers, belonging is its brightest thread. “[Link] a dazzling full-length debut that proves her gloriously idiosyncratic style shines just as brightly at scale,” writes Publishers Weekly in its starred review. “[She] dexterously somersaults between tonal registers—from playfully whimsical (love and magic are both explained via a comparison to asparagus) to hair-raising and uncanny (a cat goes from grooming itself to devouring itself whole)—without ever missing a step. This is a masterpiece.”

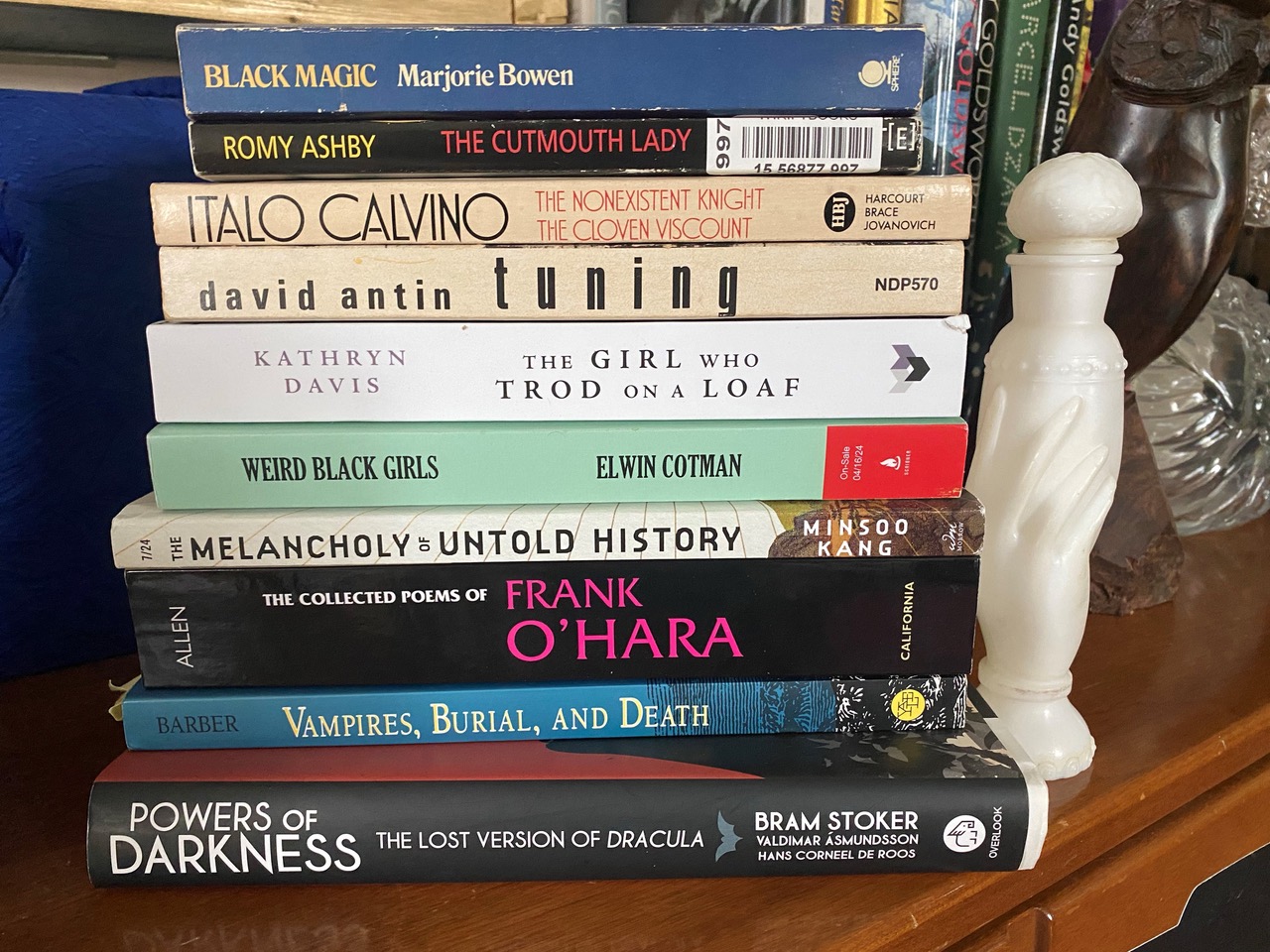

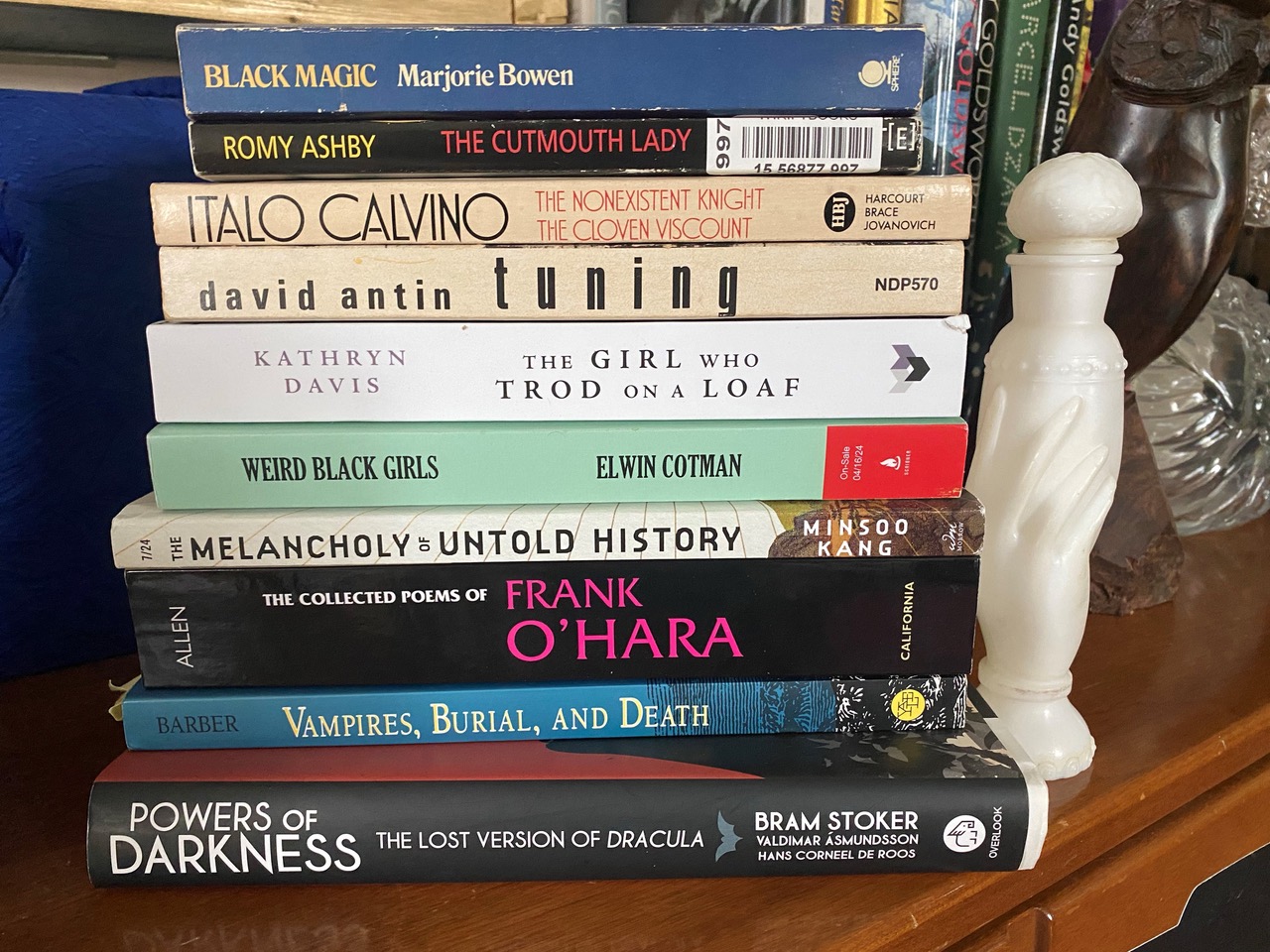

Link tells us about her to-read pile, “If I were to try to describe this reading pile, I guess I’d go with something old, something new, something borrowed, something blue. I’m thinking about a new project, a very short ghost story novel. There’s something inelegant about that phrasing, ‘ghost story novel,’ but I think it tells you the genre, and I very much want this new novel to feel like a short story.

During the fermentation stage of novel writing, I read (or reread) a Kathryn Davis novel, because of how she rearranges my sense of how language and structure can function. Vampires, Burial, and Death by Paul Barber is an old favorite that I’m rereading while I think about ghosts and resurrection. Calvino is because I haven’t read much Calvino, and that’s a terrible omission. Tuning is a loan from a friend, and I’m enormously excited to read the two galleys here, Elwin Cotman’s Weird Black Girls and Minsoo Kang’s The Melancholy of Untold History.

I read Frank O’Hara for his generosity, to remind me that we write for friends and people we care about, but we can also describe the world we see with that same spirit of expansiveness and good humor. What you can’t see in this photo is that there is a reading stack behind this stack, and a stack behind that one and so on. There are far too many good books in the world, and more are being written every day. But that’s a good thing, right?”

Marjorie Bowen, Black Magic: A Tale of the Rise and Fall of the Antichrist

Reading of Bowen’s life seems, often, like something outside of Dickens. Her alcoholic father abandoned the family (Bowen, her sister, and mother), when Bowen was a child. He turned up dead on a London street. Bowen’s mother didn’t seem to have much love for her children, and they were all impoverished by the patriarch’s flight. Bowen wrote her first novel at sixteen, The Viper of Milan, set in the fourteenth century.

While initially rejected considering Bowen’s “tender” age and the novel’s violence, it was eventually published and a huge success. Bowen didn’t stop writing and, by the end of her life, had penned Gothic horror, historical novels, mystery, short stories, historical romance, nonfiction history books, and more. She had about as many pennames as genres in which she wrote, employing each depending on the genre. Published in 1909, Black Magic is set in the Middle Ages in Europe. A woodcutter who practices dark arts finds a nobleman to join him, potentially, in the journey of accessing power through the devil.

Romy Ashby, The Cutmouth Lady

In The Cutmouth Lady, set in Hamamatsu, Japan, the community begins to hum over the fact several schoolgirls have encountered a woman wearing a face mask. The girls are usually near water—by boathouses or bridges—and are initially unafraid as the woman courteously asks them questions. Then she begins to scream and rips off her mask. Her mouth is a wound.

Hiromi narrates the novel, a girl who attends a Catholic school but connects with other outsiders and deviants like herself. Hanna Andrews writes in Weird Sister of Ashby’s novel, “It is incredibly rare that a book’s authority figures, heroes, sages, villains, criminals, and love interests are all women. Centered around female experience and desire, this book gives so much agency to the teenage girl and explores queer identity, secrecy, tradition, friendship, and family amongst familiar teen tropes like clothes, makeup, comic books, drinking, and dating.”

Italo Calvino, The Nonexistent Knight and The Cloven Viscount (tr. by Archibald Colquhoun)

This volume is of two novellas, as the jacket copy states: “the first, a parody of medieval knighthood told by a nun; the second, a fantasy about a nobleman bisected into his good and evil halves.” Jonathan Lethem in his essay “Italo for Beginners” says of the author, “Calvino, with his frequent references to comics and folktales and film, and his droll probing of contemporary scientific and philosophical theories, had encompassed motifs associated with brows both high and low in an internationally lucid style, one wholly his own.”

As a complete and wild aside, I had a professor who, decades prior, was received by Calvino in his apartment in Paris. Apparently, Calvino’s wife, Esther Judith Singer, had an unbelievable collection of masks from all over the world that covered the long hallway to the room where Calvino waited for his guests. The then-young professor stopped and marveled at them, and Singer said, “Thank you! No one ever notices them. They’re always just—‘Italo, Italo, Italo!’”

David Antin, Tuning

Originally published in 1984, this poetry collection is of the performance artist and writer known especially for his “talk poems”—improvisational pieces Antin performed in front of audiences beginning in the 1960s. The jacket copy reads, “[Tuning] is a book of eight thematically related performances—a single structure built out of loosely fitting, overlapping pieces enclosing some central space like a shingled workshed.

The ideas that appear here, the characters that come to mind, seem again and again to be involved with problems arising from a misconceived notion of ‘understanding’—as if in life experience there were an ideal, geometric congruence between idea and thing—that ignores the crucial, human question of how we arrive at a ‘common knowing.’ But how common and for how long? And how is it, starting from different places and experiences, traveling by different pathways and at different paces, we can come to a common knowing?” You can access dozens of recordings and videos of Antin’s talks, discussions, and performances over at PennSound.

Kathryn Davis, The Girl Who Trod on a Loaf

In her 1993 New York Times review of Davis’ novel, Maggie Paley writes, “Like opera, Kathryn Davis’s novel ‘The Girl Who Trod on a Loaf’ is heated, dramatic, grand in its ambition and sometimes transporting. The resemblance to opera is not accidental. The narrator, Frances Thorn, tells us she has inherited an unfinished opera from Helle Ten Brix, a cranky old Danish lesbian composer, with the expectation that she’ll finish it…‘The Girl Who Trod on a Loaf’ is a philosophical novel that examines feminist ideas and asks a woman artist’s questions (is it possible to have both work and love? how ruthless does art have to be?) in a consciously female way. The technically dazzling author of one previous novel, ‘Labrador,’ Kathryn Davis composes and orchestrates her prose to embody the all-inclusive, feminine sensibility of which she speaks.”

Elwin Cotman, Weird Black Girls: Stories

Publishers Weekly says of Cotman’s forthcoming story collection, “Cotman (Dance on Saturday) utilizes magical conceits and pop culture references to probe America’s legacy of racism in this striking collection. In “The Switchin’ Tree,” set in the 1950s, a young Black boy named Jesse walks along the highway, eliciting racial slurs from white motorists. After the boy returns home, his drunken father says he’s going to beat Jesse for wandering off, then hears a voice from a tree, and tells the tree he’s trying to protect his son from the white lynch mobs he remembers from his own childhood… The distinctive and troubled characters make these stories stand out. Cotman’s versatile talents are on full display.”

Minsoo Kang, The Melancholy of Untold History

On Minsoo Kang’s debut novel, Yoojin Grace Wuertz sells it with the remarkable overlaps the story provides when she states, “In these strange, difficult times when fiction writers (and readers!) must be wondering how invented stories can possibly compete with the twists and turns of contemporary reality, Minsoo Kang has written a novel that amply rises to the challenge.

The Melancholy of Untold History is a fabulist narrative told by a modern-day historian, a two-thousand-year-old storyteller awaiting execution by a merciless emperor, and a panoply of potty-mouthed deities. Think Game of Thrones crossed with Moana crossed with office hours at an Ivory Tower university…It is an exhilarating carnival ride that whirls between myth and love story, intellectual asides (the author is a historian) and the most colorful fart jokes ever written in English. The reader is meant to hold on tight and keep her wits about her. If she can do this, then she will be rewarded with golden dumplings from the diaper of a Sky Baby.”

Frank O’Hara, Collected Poems (ed. Donald Allen)

This is the second posthumous publication of O’Hara’s work but the first to win an award. It shared the National Book Award for poetry (have now learned this has happened—apparently also to Adrienne Rich and Allen Ginsberg once) with Howard Moss in 1972. While I hesitate to hope I’ll inform you of something new about O’Hara, I will share what I learned for the first time.

While I knew he was in the Navy during WWII, I didn’t know he was in the South Pacific—a region I now know was defined as deadly, brutal, and traumatizing for all involved. He also had the future-author and artist Edward Gorey as a roommate at Harvard, and seriously studied piano. O’Hara spoke to Donald Allen in an interview and stated of his poetry, “What is happening to me, allowing for lies and exaggerations which I try to avoid, goes into my poems. I don’t think my experiences are clarified or made beautiful for myself or anyone else, they are just there in whatever form I can find them.”

Paul Barber, Vampires, Burial, and Death: Folklore and Reality

“An armchair Dr. Van Helsing tracks down the real origins of the vampire legend” begins the 1988 (!) Kirkus review of this book. “Vampirism can result, [Barber] finds, from suicide, sorcery, inauspicious birth, having a sleep-walking brother, and other rips in the social fabric. Unlike screen Draculas, folklore vampires are usually ruddy, bloated, lightly bearded peasants. To keep a vampire from leaving his grave, try mutilating the corpse, filling the burial site with food or knots (vampires can spend centuries happily untying knots), burying the corpse face-down (the vampire will chew his way to the center of the earth), etc. If the vampire escapes, recommended steps include staking, cutting out the heart, or cremation.

After delivering this fascinating Baedeker of the living dead, Barber turns to an examination of human decomposition, explaining how each stage contributes to the vampire legend (bloating of the corpse, for instance, leading to reports of disturbances of the earth over a vampire’s grave).” I love, especially, how the review ends: “Learned, energetic, creepily absorbing study—definitely not for children.”

Bram Stoker & Vladimir Ásmundsson, Powers of Darkness: The Lost Version of Dracula (tr. Hans Corneel de Roos)

Three years after Dracula came out in 1987, the Icelandic writer Vladimir Ásmundsson serialized his translation of the story—but infused it with Norse myth, as well as more overt sexuality and violence. The person who “discovered” Makt Myrkranna or Powers of Darkness and translated it into English, Hans Corneel de Roos, wrote here at LitHub, “In Powers of Darkness, the Count has even more female companions, who invariably are stunningly beautiful, just like the victims of his coven—girls who are brought into his barbarian temple in shackles, virtually denuded.

One might argue that for Bram Stoker, who had to delete parts of his Dracula manuscript in order to have it published by Constable, the publication in Iceland meant an opportunity to launch an uncensored version of his vampire tale…[Yet] Stoker wrote in 1908 in a defense of censorship. It is hard to imagine that the same author would have indulged in creating the titillating nude scenes we find in Powers of Darkness. I rather suspect that Valdimar Ásmundsson, who in the 1901 book version is listed as the translator of Stoker’s narrative, acted as the Irishman’s co-author.”

Diana Arterian

Diana Arterian is the author of the recent poetry collection Agrippina the Younger (Northwestern UP, 2025) and editor and co-translator of Smoke Drifts (World Poetry Books, 2025), a collection of Nadia Anjuman's poetry. A Poetry Editor at Noemi Press, Diana has received fellowships from the Banff Centre, Millay Arts, and Yaddo. She writes “The Annotated Nightstand” column at Lit Hub and lives in Los Angeles.