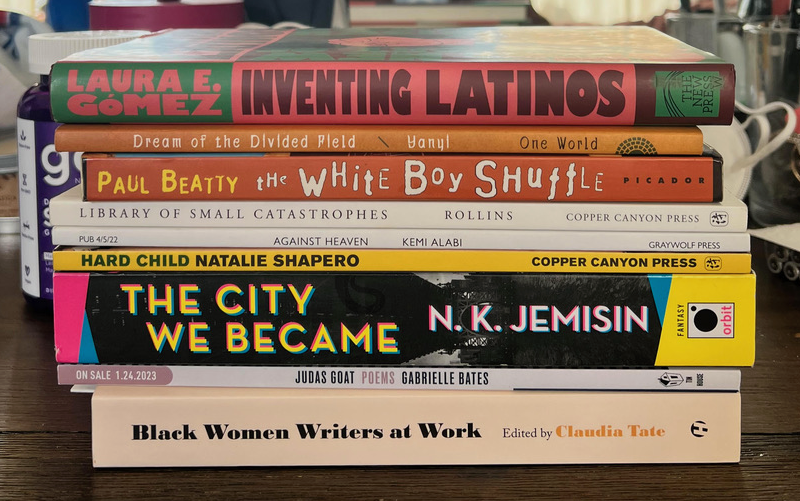

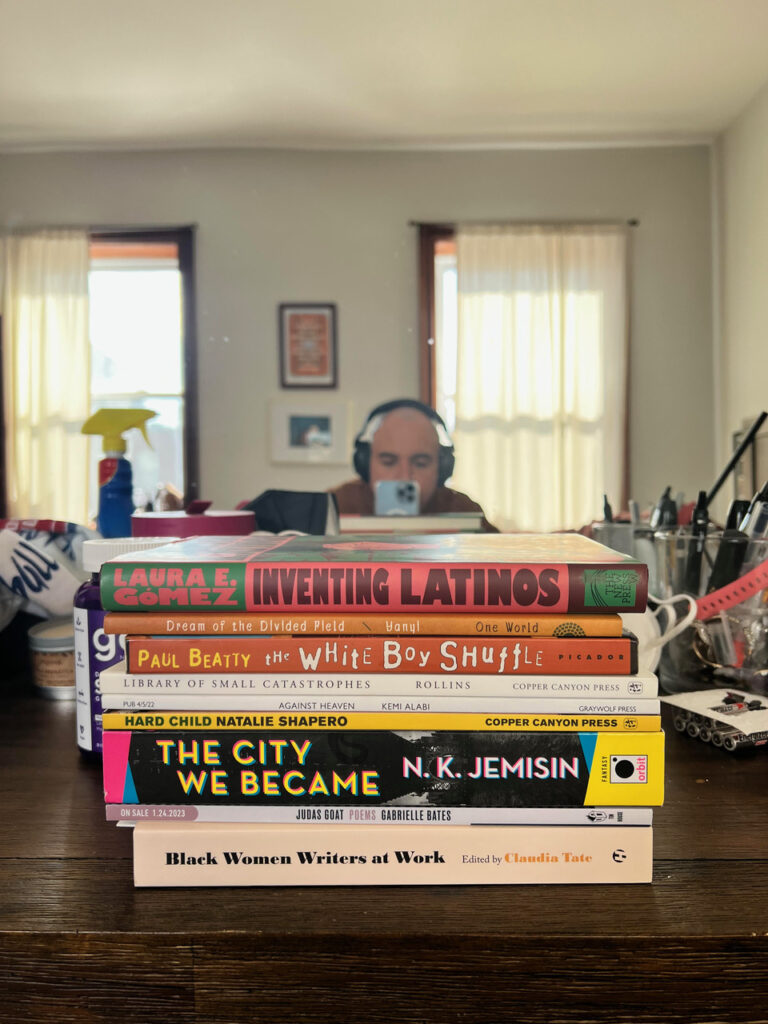

The Annotated Nightstand: What José Olivarez is Reading Now and Next

Featuring Paul Beatty, N.K. Jemisin, Yanyi and more.

José Olivarez is the author of the 2018 poetry collection Citizen Illegal. In it, Olivarez interrogates a series of concerns largely circling around his experiences as a child of undocumented parents from Mexico. In an interview in the New York Times after Citizen Illegal was published, Olivarez described a childhood defined by the hope that overachieving in his Illinois town would lead to acceptance from his Anglo peers. Perhaps unsurprisingly, though no less disappointingly, Olivarez found his tactic didn’t work out in the way he hoped.

In the aftermath, he states, “I started writing, and I turned to black literature, [and] it did unlock this idea that I actually didn’t want to participate in America as constructed. I wanted to construct a world where I didn’t have to erase parts of myself. Poetry gave me a space to talk about the in-betweenness that I felt.”

Olivarez has a new book out this month entitled Promises of Gold /Promesas de Oro, translated into Spanish by David Ruano González for this bilingual collection—an exciting thing to see, considering how rare such collections are from large presses (and usually from rather than into a language other than English). In the introduction to the book, Olivarez writes, “Promises of Gold is what happens when you try to write a book of love poems for the homies amid a global pandemic that has laid bare all the other pandemics that we’ve been living through our whole lives. Capitalism is a pandemic. The police state is a pandemic. Colonialism is a pandemic. Toxic masculinity is a pandemic.”

Indeed, throughout in a series of poems that take form in free-verse, sonnets, prose poems, and text message screenshots, Olivarez interrogates the concerns of the many systems that hound us all, to different degrees of danger, depending on the levels of vulnerability we carry. A poem entitled “Ojalá: I Hate Heartbreak” is particularly moving, as it describes Olivarez’s suicidal ideation after a breakup—walking where there were cars “suddenly dangerous.”

After calling a friend nearby, the friend comes and walks Olivarez home, holding his hand on the way. “oh god, i praise this touch—untranslatable, / which is how i know it’s holy.” This underscores the starred review of the collection in Publishers Weekly, which argues the poems do the work of “revealing how close bonds are an antidote to the world’s hardships.”

On his book pile, Olivarez states, “I mostly read poetry, but I’m trying to be better about broadening my reading. My next project is to write a novel, so I’m curious about that form. A homie told me she learned to write fiction by reading hella romance novels, so don’t be surprised to find a bunch of Harlequin books on my nightstand in the near future.”

Laura E. Gómez, Inventing Latinos: A New Story of American Racism

The UCLA professor Laura Gómez interrogates Latinx racial identity which, Gómez argues, fell under a broad umbrella of singular identity only in recent history. In its review, Publishers Weekly states, “[Gómez] examines how geographical separation (Cubans in Florida, Mexican Americans in the Southwest, Puerto Ricans in the Northeast) and cultural differences forestalled the emergence of a Latino civil rights movement until the 1970s, and notes the ‘seismic reverberations’ on American politics and popular culture of counting Latinos in every U.S. census since 1980… This incisive survey of Latino history packs a knockout punch.”

Yanyi, Dream of the Divided Field

The winner of the Yale Younger Poetry Prize in 2018 for his collection The Year of Blue Water, Yanyi’s latest collection came out last year. In it he effectively considers longing of different shapes—amorous, as well as realization of identity. In one poem, he describes a yearning for a future after top surgery. Yanyi writes, “I bring a picture to the hairdresser. I bring / a picture to the mirror where I cut my skin / with my eyes.” In another poem about the separation from a lover, he employs compelling and novel metaphor when he states, “I am not so different from the long hare / stretched by her shadow, / her spirit hanging.”

Paul Beatty, The White Boy Shuffle

His first novel is about as well-known as Beatty’s later award-winning novel The Sellout, which garnered him the NBCC in Fiction and the Booker Prize. Beatty’s earlier book follows the protagonist Gunnar Kaufman through a satirical bildungsroman set in Los Angeles (Beatty’s home town). Racial dynamics, Blackness, and sexuality all are big threads in the book. What I was surprised to learn is that Beatty is, also, a poet. And not only that—he holds the particular prestige of being the first to ever Grand Poetry Slam Champion of the Nuyorican Poets Café in 1990. If you don’t know of the Nuyorican Poets Café, I highly recommend diving into its rich history.

Alison C. Rollins, Library of Small Catastrophes

This is a book that has been on my list of ones to read, but it keeps slipping away (mostly as I remember at AWP, and all the copies are gone). Rollins is a librarian at the School of Art Institute of Chicago. Her knowledge and life in the library drives the collection. Naomi Shihab Nye writes of the book, “In a stunning debut collection of poems, Alison C. Rollins makes use of imagery relating to archives, texts, figures from history, card catalogs, classifications — libraries as evocative troves of imagery, blurring eras, familiar phrases and identities.”

Kemi Alabi, Against Heaven

Alabi’s poetry collection won the Best Book of 2022 from the New York Public Library, the Academy of American Poets First Book Award. In an interview in Apogee Journal, they explain, “I find vulnerability really pleasurable, but that’s not where I usually begin when I write. I’m always playing with sound, trying to find the line, and letting language lead me somewhere. I’m satisfied with what I’ve found when the real shit pops up, and that’s what I can revise toward. Black feminist writers taught me the urgency, political potency, and transformative power of truth-telling, and the only truth I’m interested in is accessed through vulnerability—I’m skeptical of its other origins. So I don’t consider this a volatile place to write through. It’s a space of aliveness and relief.”

Natalie Shapero, Hard Child

Shapero was shortlisted for the Griffin Poetry Prize for this collection in 2018. The judges state of her work: “The poems in Natalie Shapero’s Hard Child come as close as lyric poems can to perfection. We feel the effect of them before noticing their machinery. Yet every poetic instinct Shapero possesses, every decision of line, image, stanza, diction, and tone, results in poems that are limber, athletic, powerful, and balanced. And behind her technical choices lie an emerging ethics: ‘I don’t want any more of what I have. / I don’t want another spider plant. I don’t //want another lover.’ Her poems take us to the purest evolutionary point of the lyric form through their single-speaker stance, the movement of a mind over subjects, the emotional weight carried on the backs of images, the unpredictable associations, the satisfying call-backs…This is how to write a lyric poem.”

N.K. Jemisin, The City We Became

When a book that’s only been around for a couple of years has its own Wikipedia page, you know it’s doing some serious work. The City We Became was shortlisted for five awards and won two. In an interview on the podcast Between the Covers, Jemisin describes cities thusly: “Cities, obviously, can be founded, obviously go through changes, periods of growth, peaks, periods of decline and decay. Frequently, cities are destroyed by natural disasters or political upheavals and things of that nature. They’re like all systems in that systems emulate life… All I’m doing is really literalizing history in that sense. The speculative element of it is simply that the cities talk and have a spokesperson or spokes voice, for lack of a better description, that an individual human being can embody some element of that city or that city’s power. I think that’s the only real speculative piece, well, that plus a vaguely Cthulhu-like-monster from beyond, and who’s to say that’s not real too?”

Gabrielle Bates, Judas Goat

Cindy Juyoung Ok reviews Bates’ first collection of poems for the Poetry Foundation and writes, “The debut’s sequences on mourning, mothers, and marriage consider the ways in which encounters with nonhuman animals reveal the deception, purchase, and stakes of human behavior… Across eulogies and love letters, Bates piercingly catalogs animals used as metaphor or foil, and wielded in a human economy.” Bates’ book considers, in many shapes, the “Judas goat”—a creature that lives with sheep and is trained to lead them to the slaughterhouse. This figure colors her descriptions of relationships, complicity, harm, love throughout the collection.

Claudia Tate (ed.), Black Women Writers at Work

Originally published in 1980s, it’s wonderful to see Claudia Tate’s vital collection of interviews recently republished. The book includes conversations with Gwendolyn Brooks, Maya Angelou, Sonia Sanchez, Toni Morrison, Margaret Walker, Nikki Giovanni—the list goes on and on. In a 1986 review, Beth Brown writes, “The purpose of [Tate’s] interviews is to capture a moment where Western culture and African heritage intersect, and male-female attitudes converge or diverge… Through this method of inquiry and the imaginative writing which has provided a number of themes, Tate has reached into the web of intentions: the character’s personal search for identity, dignity, and strength, and the way women writers have come to project themselves, in terms of gender, from the point of view of female character.”

Diana Arterian

Diana Arterian is the author of the recent poetry collection Agrippina the Younger (Northwestern UP, 2025) and editor and co-translator of Smoke Drifts (World Poetry Books, 2025), a collection of Nadia Anjuman's poetry. A Poetry Editor at Noemi Press, Diana has received fellowships from the Banff Centre, Millay Arts, and Yaddo. She writes “The Annotated Nightstand” column at Lit Hub and lives in Los Angeles.