The Annotated Nightstand: What Garth Greenwell Is Reading Now, and Next

Featuring Mark Haber, Noor Naga, Mavis Gallant, and Others

It’s unlikely a novel that begins with a person left immobile from pain will have him enter a hospital to just have his appendix removed (as the unnamed protagonist of Garth Greenwell’s Small Rain initially thinks). Despite his pain, he fights going at all: “Only if you were dying would you go to the hospital,” he explains, “and it didn’t occur to me that I could be dying.”

He hopes he can go home very soon. Perhaps even a course of antibiotics will be enough. After a bleakly quotidian wait in the ER that lasts hours on end, the grip of the man’s physical precarity tightens with each paragraph. He is given information he can’t fully comprehend, delivered speedily and with confusing language by healthcare practitioners.

Eventually he learns/pieces together he has had an aortic tear, which statistically should have killed him. It might still kill him. He will be in the hospital for he doesn’t know how long during the height of the pandemic, allowed only one visit a few hours a day from his partner.

The first pages of Small Rain filled me with terror. It was like watching a person enter a prison in increments, fully compliant and wholly unaware of his dire circumstances and powerlessness until the iron door slams shut.

Once the central figure of Small Rain is sequestered to his hospital bed, the novel brought to mind Roberto Bolaño’s 1999 novel Amulet. In that short novel, a poetry professor hides in a bathroom stall for two weeks while the university is occupied by police and soldiers. Like the protagonist of Small Rain, she is in a fraught and isolated situation. As her hunger intensifies, her mind roves through her memories.

In the case of Greenwell’s main character, who experiences inevitable disorientation in the hospital and reliant on oxy to coast through his terrible pain, we gain more of the speaker’s life prior to this crisis. These are often through poignant flashbacks triggered by the embrace of his beloved, or while listening to a piece of music.

As the days crawl by, he enters into increasingly extended eddies of life stories. (These often happen when we are the precipice of learning an important piece of information, like the results of a test, keeping us in vigilant suspense while also in the thrall of, say, a memory of a tryst.)

Simultaneously, he begins to take note of the potential long-lasting impacts of his ailment, as when he realizes he hasn’t masturbated or orgasmed since entering the hospital, an otherwise daily experience. He is suffused with a terror at losing desire or the physical capacity to get hard. “It was impossible to imagine,” he says. “I would be a different person entirely, a prospect I considered with a mixture of panic and relief, would I even be recognizable to myself, who would I be.”

Small Rain’s protagonist has many of the markers of Greenwell, who also had a terrifying near-death experience from the same ailment, though he recovered far more quickly than his main character. (Greenwell consistently pushes back on his work being “autofiction.”)

One difference between them is the novel’s ill patient previously has built his life around poetry, rather than fiction. “Any life centered on a single object of devotion is a gamble,” Greenwell said at a recent event for Small Rain. For, if that particular devotion doesn’t bear you through life’s most physically (and thus existentially) desperate moments, what value does it really have?

That said, as Greenwell explains in an interview with Ruth Madievsky, “I really do believe that the whole reason we have art is because there are questions or situations or conundrums that defeat all our other tools for thinking.”

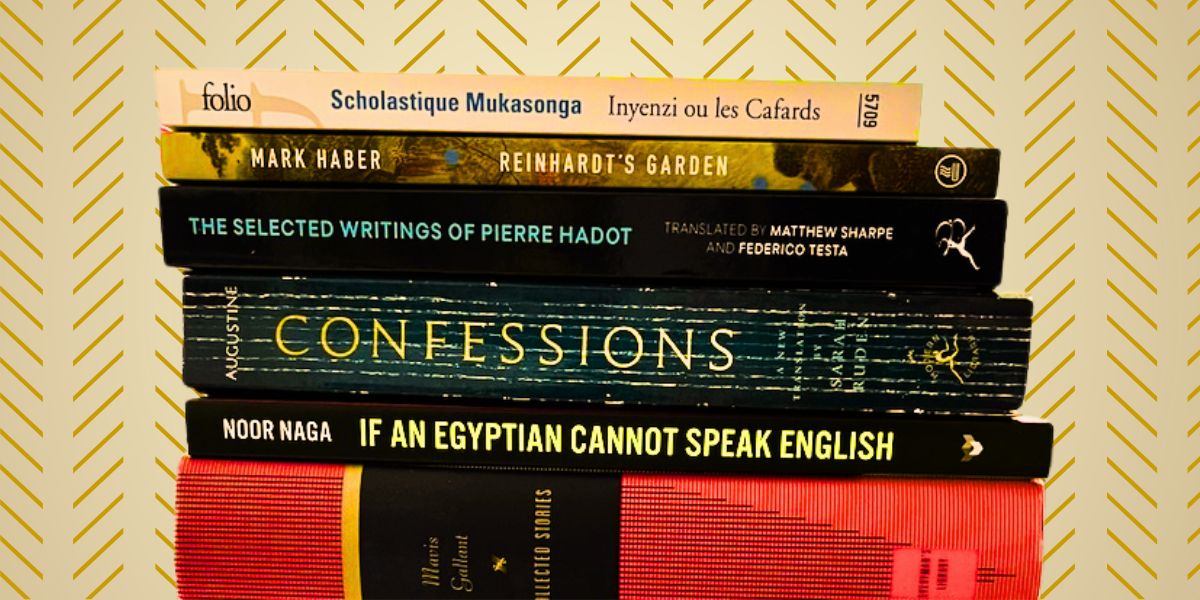

Greenwell shares his to-read pile, saying,

In this pile, a mixture of reading for projects (a seminar on Henry James, an essay on Augustine) and pleasure. Some novels I’ve long wanted to read, and one (Mark Haber) I’m rereading before devouring his newest. And Arthur Sze is such a great maker of images reading him is a kind of sunbathing. All novelists could benefit from basking in the light of these poems.

*

Scholastique Mukasonga, Inyenzi ou les Cafards

This memoir by the award-winning writer Mukasonga, a Rwandan-French woman who survived the 1959 pogroms against Tutsis, was translated into English by Jordan Stump under the title Cockroaches (an epithet Hutus used for displaced Tutsis). While Greenwell is reading Mukasonga in her original French, Lynne Sharon Schwartz writes in a review of Stump’s translation in the Los Angeles Review of Books,

It is history on the human scale, endured by a tight community in the grip of uncontrollable forces: a compelling story of what happened to the author, her parents, and six siblings beginning in 1963, a year after the country gained its independence from Belgium.

Schwartz goes on,

Cockroaches is not political history; that has been told in books by journalists and scholars. It is the truer history of individual lives. It is indispensable reading for anyone who cares about the endurance of the human spirit and who hopes for a better world. The conclusion is a stunning illustration of how precious little this courageous author has salvaged from tragedy.

Mark Haber, Reinhardt’s Garden

David Naimon interviewed Haber about Reinhardt’s Garden for his sublime podcast Between the Covers. During their conversation, Haber tells Naimon,

This book would not exist without translated literature. It just wouldn’t. I’ve wanted to be a writer since I was seventeen but it would probably be some kind of diluted attempt at like Saul Bellow or something….Basically, the shape and the size of the style of the book itself is definitely influenced by [César] Aira. Those tiny books that are compact but so much happens in them.

Haber goes on,

I love this idea of extremely obsessed characters that are maybe a little bit maniacal. I can’t really do subtlety. I wish I could. I see writers that do vary quite writing and what appeals to me and what I think my strength is writing characters that are on the high end, they’re very obsessed, they’re very driven…I think Saul Bellow called them ‘high-IQ morons.’ I love people who are really, really smart and intelligent but their entire obsession is almost like an act of self-sabotage where what they’re doing is to the detriment of themselves and obviously, in Reinhardt’s Garden, everyone around them.

Pierre Hadot, The Selected Writings of Pierre Hadot: Philosophy as Practice (trans. Matthew Sharpe and Federico Testa)

Hadot was a French philosopher who introduced his nation to Wittgenstein’s work—a nice feather in one’s cap, to say the least—and had a sizable impact on Michel Foucault’s thinking. Yet what compelled me most about Hadot’s biography is that, at the age of twenty-two, he was an ordained priest. Six years later, Pope Pius XII promulgated Humani generis (Of the human race).

As a never-Catholic and layperson, it’s a bit hard for me to parse the particulars. But, the likely sticking point for Hadot, is that it seems French theology was moving toward inquiry and research regarding doctrine and belief. Humani generis halted it.

It is now doubted that human reason, without divine revelation and the help of divine grace, can, by arguments drawn from the created universe, prove the existence of a personal God; it is denied that the world had a beginning; it is argued that the creation of the world is necessary, since it proceeds from the necessary liberality of divine love; it is denied that God has eternal and infallible foreknowledge of the free actions of men – all this in contradiction to the decrees of the Vatican Council,

writes Pope Pius XII. “These and like errors, it is clear, have crept in among certain of Our sons who are deceived by imprudent zeal for souls or by false science.”

The TLDR: teach what we decree, and nothing else. Toe the line. Hadot left the church the same year, and married Ilsetraut Hadot, a fellow philosopher and historian, three years later.

Augustine of Hippo, Confessions (trans. Sarah Ruden)

Just look at all those spine breaks on this much-loved copy! What new thing can I say about Saint Augustine that hasn’t already been said (or Greenwell won’t express more adeptly in his own forthcoming essay)? I love that the Berber bishop is the patron saint of brewers and painters. As a theologian, Augustine had a deep interest in Stoicism, creating a nice overlap with Hadot’s central concerns (Hadot has written about Augustine).

People argue Confessions is the first memoir written by a Western author, as Augustine describes his wayward youth prior to his conversion. His trespasses? He reads literary (non-scripture) texts, has a child with an unwed partner, believes in astrology, is a Manichaean, and enjoys some sexual romps. Honestly feels like a pretty blessed Millennial American life to me!

But of course, as with most memoirs, Augustine has a precipitating event that ultimately leads to his conversation: a dear friend dies and he falls into a deep depression, realizing that well of sadness is particularly cavernous due to his lack of faith in a God that could suffuse him with love, instead having a real “Paint It Black” view of the world. His Manichaean faith starts to falter, he meets a charismatic Catholic bishop, and the rest is history.

Noor Naga, If an Egyptian Cannot Speak English

Naga’s novel focuses on an Egyptian-American woman and a man from a small village outside of Cairo, where they meet and begin a love affair after the Arab Spring. He documented the revolution in photographs for news outlets, but his income has dried up as an uneasy peace has settled in.

Nadia Owusu reviews this Winner of the Center for Fiction First Novel Prize in The New York Times, writing,

The relationship between the two lovers eventually sours for the very reasons that they are initially drawn to each other. He wants her wealth but resents her for having it. She wants his authenticity but hates that he lords it over her….Their resentments escalate. Eventually, he becomes violent.

Owusu continues,

But Naga doesn’t allow the reader to rest in easy notions of right and wrong or culpability and innocence….Just when you think one character has crossed a line, the other reaches out and touches a third rail, causing the reader to ask, Whose story is this, anyway? This question—about whose version of a story, or of history, gets told, and why—is at the heart of this exhilarating debut.

Mavis Gallant, The Collected Stories

Francine Prose writes in her introduction to Gallant’s Collected,

No one provides more concrete and factual information (details of personal and European history and politics, of family, employment; brushstrokes that establish a city, a subculture or a domestic constellation) while at the same time making you feel as if you suddenly understand something essential about human life, something that perhaps you always knew, though you still can’t begin to express it. No one’s characters (young and old, male and female, rich and poor, from at least a dozen different countries) are more meticulously rendered.

The characters’ specificity makes us feel simultaneously delighted, enlightened, and choked up. With a masterly control of tone that allows her to locate the perfect point on the continuum between engagement and detachment, and with a view of character at once scathing and endlessly tolerant and forgiving, Gallant displays an almost preternatural gift for making readers not only meet but care profoundly about men and women and children whom they otherwise wouldn’t have met and might not have chosen to know.

She accepts and reveals our flawed and complex human nature without pretending that our problems have solutions, or that experience—even tragic experience—necessarily changes or improves us.

Kevin Ohi, Henry James and the Queerness of Style

Ohi’s book is from University of Minnesota Press, the dreamiest of scholarly presses that has put out the likes of Grace M. Cho, Dana Seitler, Akira Mizuta Lippit, and essentially every other theorist I cited in my dissertation. In his introduction, Ohi writes,

Henry James and the Queerness of Style seeks to trace such a “nonpreexistent foreign language” in the writings of Henry James and thereby to find in James’s style a queerness that, not circumscribed by whatever sexualities or identities might be represented by the texts, makes for what is most challenging about recent queer accounts of culture: a radical antisociality that seeks to unyoke sexuality from the communities and identities—gay or straight—that would tame it, a disruption that thwarts efforts to determine political goals according to a model of representation, the corrosive effect of queerness.

You can see Ohi speak on Henry James and queerness here.

Peter Brown, The Body and Society: Men, Women, and Sexual Renunciation in Early Christianity

“First published in 1988, The Body and Society became a groundbreaking study in the practices of permanent sexual renunciation, of continence, celibacy and lifelong celibacy, among Christian circles from the first century to fifth century AD,” writes Kevin Kia-Choong Teo in a review for Bryn Mawr Classical Review.

In lieu of using “practice,” I use “practices” to describe the act of sexual renunciation in the context of this book, especially because Brown’s book can be read as more than just a testimony to the pluralistic expressions of sexual renunciation in the late Roman (and early Christian) world. Its structure can also be read as an intellectual journey through the theological-social terrains of early Christianity. Its chapters can be read both as isolated chapters and as units leading to one another, confounding the idea of Christianity in the late Roman world as monolithic in its views and practices of sexual renunciation.

Martha C. Nussbaum, The Fragility of Goodness: Luck and Ethics in Greek Tragedy and Philosophy

I always love to dig up older reviews, especially for reissued texts. Charles Taylor writes in a 1988 issue of Canadian Journal of Philosophy:

This is an immensely rich and stimulating book. This is partly because the author combines to a rare degree qualities not often found together: a scholar’s understanding of the text with rigor of argument, and these together with an imaginative grasp of moral questions.

But it is also because she has chosen to write a very ambitious book, to grapple with some fundamental, perennial issues. The theme might be summed up in a single sentence in the terms of the subtitle: what is the place of luck or chance in moral goodness, as this is variously understood by Greek tragedians and philosophers?”

Taylor goes on:

In our time, we may be tempted to think that luck has nothing to do with goodness, because we are inclined to define this latter purely in terms of intention. Nussbaum points out how much contemporary moral thinking is under Kantian influence. It is the quality of the will that matters, and that is independent of fortune. What happens to us may affect our happiness, will certainly determine how much good we manage to do; but it can’t touch what we intend, and that alone is relevant to the moral quality of our lives.

Arthur Sze, The Glass Constellation: New and Collected Poems

Jennifer Elise Foerster, a former student of Sze’s, writes of his 2021 collection in The Georgia Review:

In class, Arthur would often ask us where we felt the “heat” in the poem: if we hovered our palm over the page, where could we feel the heat radiating? In the poem-mind, this makes perfect sense—the heat intensifies as the poem’s images and sounds spiral and knot. In wave dynamics, the poem is hottest when the amplitude and frequency is highest.

Can an image affect frequency? Can one thought alter the way a given wave travels? The mind zig-zags, Sze says, it “shifts as the world shifts. /. . . / The world shifts as the mind shifts.” The mind, he writes, “is a tuning fork that we strike, and, struck, in the syzygy / of a moment, we find the skewed, tangled / passions of a day begin to straighten, align, hum.” There is harmony—tuning—in the looping mind, one that notices, glances, turns, senses, ponders—all operative verbs in Sze’s poems….

The Glass Constellation is a seminal and distinct collection, offering an immersion in Sze’s expansive and exacting poetic imagination. We can follow the evolution of Sze’s poetics from his early painterly and contemplative style to one of radical attunement.