The Annotated Nightstand: What Eugene Lim Is Reading Now, and Next

Featuring Paul Yamazaki, Richard Brautigan, Pamela Lu, and Others

Amazed to say this is the fiftieth post in “The Annotated Nightstand” column! Whew. Thank you, LitHub!

Now, to get to business: Eugene Lim’s Fog & Car was originally published in 2008 and has just been reissued by Coffee House. The plot-driven description is it follows two young people—Fog and Car—after they divorce. In this new edition, the inimitable Renee Gladman, one of the blurbers for the original, writes in her introduction of “the uniquely intimate and unsettling way Lim reveals the precarity of their aloneness.”

Initially, through alternating chapters, they seem to emulate their names. Fog’s life is unmoored after he has moved back to his rural Ohio hometown to be a schoolteacher. This uncertainty emulated in the text itself with brief paragraphs, lots of white space. Car, on the other hand, has moved to New York, lined up an apartment and a job, starts swimming for exercise. She is on a path, chugging along.

But eventually things get soupy for her and sharpen for Fog. And there’s an ex-best friend of Fog who ghosted, that fracture potentially changing Fog and Car’s marriage. Car sees him in New York and starts to follow him.

One of the beautiful things about Fog & Car is how (like the recent works of Anna Moschovakis, K-Ming Chang, Caren Beilin), despite the trajectory of the characters, it is a slow burn. The predominant sense of the book is the existential angst in changing your life by taking someone out of it.

Ennui and the odd pursuits to drive it away, or explore it, were some of the most exciting moments for me. We see Car chase an ice cube with her nose across the ground until she gets it in her mouth. Fog, on impulse, slowly makes his way up an isolated crag, handhold by foothold, only to appreciate the danger once he’s at the top.

In short: it’s mood-driven, and hard to put down. Hua Hsu writes of Lim’s work in the New Yorker, stating his novels are those “that flexed his fragmentary and quietly unnerving style. His writing is confident and tranquil; he has a knack for making everyday life seem strange.”

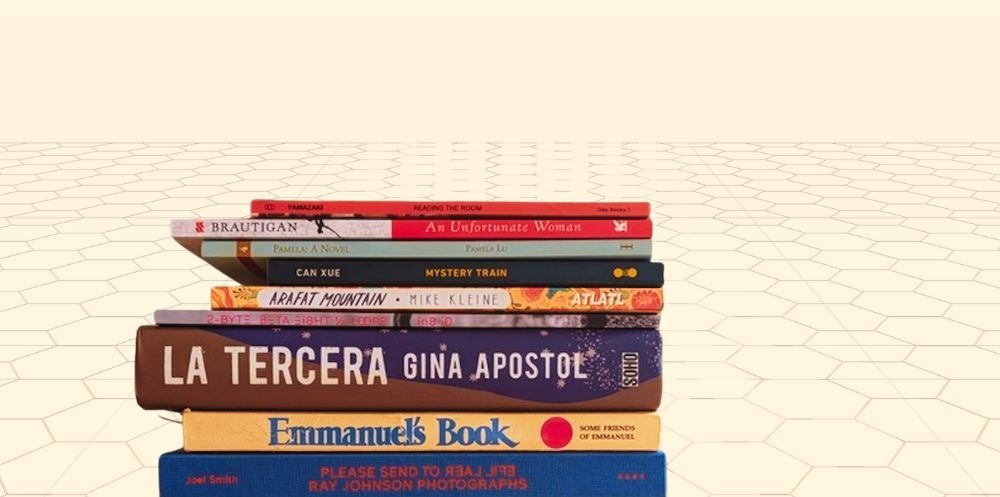

On his to-read pile, Lim states,

Piles of books I like to think of as hard clouds of ideation I’ve scattered around the apartment (as opposed to admitting I’m a slob with books)….I was with a friend in San Francisco this past weekend and we chanced upon the Ben Franklin statue in Washington Square, which prompted (her to recommend Brautigan’s An Unfortunate Woman but also for) us to exchange poems, and she gave me the beautiful “Your Catfish Friend,” and I gave her “All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace,” which, coincidentally, was a poem that had just been introduced to me days before by the author of 2-byte βeta Ei8ht ½-Loopƨ (also coincidentally one of three books in the pile with reversed type in their titles) and so, by just, breathlessly mentioning a few, we see (once again) how many stories are not only in a stack of books but also to and from.

*

Paul Yamazaki, Reading the Room: A Bookseller’s Tale

Yamazaki served as the principal book buying for the legendary San Francisco bookstore City Lights for half a century (!). City Lights was founded in the 1950s by Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Peter D. Martin (the latter of whom made a relatively quick exit). In an interview in 2005, Ferlinghetti is quoted as saying, “I keep telling people I wasn’t a member of the original Beat Generation. I was sort of the guy tending the store.”

Paul Yamazaki, an activist who grew up in Southern California, was brought in in 1970, and has been there ever since. The wonderful author Karen Tei Yamashita writes of Reading the Room, “I love this little book….It’s a love story to books and City Lights….Browsing is everything, and curating [City Lights’] space—its magic, possibility, and freedom—is Paul’s unique gift and genius.”

Richard Brautigan, An Unfortunate Woman: A Journey

This slim posthumously published semiautobiographical novel was reviewed in Publishers Weekly, where they write,

The narrator, clearly the talented, alcoholic, sexually questing Brautigan, explains his rambling account as “a calendar of one man’s journey during a few months of his life.” The episodic entries, dating from January to June of 1982, at first seem whimsically random, as the narrator recounts a peripatetic six months wandering among Montana, Berkeley, Hawaii, San Francisco, Buffalo, the Midwest, Alaska, Canada and points in between, but soon it’s obvious that a preoccupation with death is the dominant theme. The narrator stays at various times in the house of ‘an unfortunate woman’ who hanged herself, and the event darkens his consciousness even when he is not physically there….Even so, Brautigan maintains his ironic humor and his ability to write clear, often crystalline prose.

Pamela Lu, Pamela: A Novel

Samuel Richardson’s Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded is a mid-eighteenth-century text that many argue is the first “true” novel (whatever that means) written in English. Richardson also invented the name Pamela for the titular character.

Aaron Kunin in his review of Lu’s Pamela in Rain Taxi interrogates the potential linkages between the two texts. He writes,

I’m tempted to argue that the only possible connection between the two Pamelas must be a subterranean one. On the surface, the two books appear to have nothing in common. Richardson’s is a domestic drama enacted mainly in scenes with only two or three characters; Lu’s is a portrait of a much larger community and is presented almost exclusively in a summary mode, even when it’s dealing with specific actions and events. Richardson wants to bring you as close as possible to the scenes in his novel, even to collapse diegetic action together with acts of writing and reading into a single moment; Lu works very hard to distance herself from any moments of intimacy by refracting them through memory, retelling, contemplation, and various technologies of representation….You could even say that the title asserts a connection between the two novels only as a way of confirming that there is no connection, or as a way of saying that we have reached a point in literary history where the original Pamela no longer means anything to us.

Can Xue, Mystery Train: A Novella (trans. Natascha Bruce)

“Can Xue’s experimental novella Mystery Train opens in total darkness,” writes Lily Nilipour in Asian Review of Books.

[A] chicken-farm employee named Scratch wakes up to find himself “in one of [the] pitch-dark sleeper cars” of a train. Confused, Scratch gets out of bed and looks at his wrist to check the time, but is unable to make out the face of his watch at all. In fact, Scratch peers around the cabin and can’t “see a thing.” He tries to recall the events that brought him to this place, but even that eludes him. As he racks his brain, a single “dim, pre-sleep memory” forms—and at that, the story slowly starts to unfold. The obscurity, literal and psychological, of the opening sets the tone for the entirety of Mystery Train, a chilling mystery-thriller translated from Chinese into English by Natascha Bruce. Darkness reigns throughout: it is the book’s defining and driving force, the thing that is always present, that none of its characters can escape.

Mike Kleine, Arafat Mountain

This book certainly piques my interest, if only because of how little information there is about it despite it coming out in the last decade (read: when Internet was around). The entirety of the jacket copy reads: “We open Google Maps. We search for life on other planets. We search for Arafat Mountain. Then we search for palm trees and things like that.”

The publisher of the French translation, Le Mont Arafat, gives us a little more:

In Arafat Mountain, there is all literature, in all its forms. In Arafat Mountain, some characters go to a castle. Someone watches a Woody Allen movie, and cries. There is Arafat Mountain, where it is said that Mohammed gave one of his last sermons. A plane disappears. There are parallel universes, and, of course, space-time travel. An island with prisoners. It is most certainly the end of the world. Gods eat other gods. And, in a room somewhere, there is a lever that, above all, you must never touch.

1-wing 2can, et al, 2-byte βeta Ei8ht ½-Loopƨ

I would be remiss if I didn’t quote this really fun/braintwisting jacket copy directly:

2-byte βeta Ei8ht ½-Loops = αlphaNumeric txt/img objet that doezn’t claim 2 B N-E-thing other than what iT eQuills 2 (den8ured eXposition of the underLying sorce code used 2 cr8 it, on sum quantum lvl) > naught only does the book eggknowledge the tecknowledgey used 2 bring it in2 ∃xistence, but iT reverses aↄcepted notions of «authorship» by inklooting u the reader in the eXpirement, folding 1 + all in2 the s&-boxed fabric of the 5elf-perpetu8ing feedbaↄk Loop…the appointed «author» (1-wing 2can, et al) amounts 2 N-E 1 that acquires, reads ± engages w/ said book (the B-Low author5hip manifest will upd8 inkrementally‡), i.e. a crowd-$ourced weigh 2 propaG8 th over-arcHing U/X project 2 the next lvl (con5ider book az Ↄalamari Arↄhive $tock certifiↄate), thx 2 yr kind in-kind 5upport—

Gina Apastol, La Tercera

Hari Kunzru reviews Apastol’s novel for the New York Times, stating,

Like Apostol, the narrator, Rosario, was raised on the Philippine island of Leyte, and her first language is Waray, the seventh most commonly spoken in the country, though she was forced to learn Tagalog at school. Her life, like that of all Filipinos, is a constant act of translation. She finds that “Spanish was for the outside things, the things you could make.” So la mesa is the table, la cama is the bed and so on, but “Warays kept their words for the inside….” Apostol’s bold and laudable choice is to assert what the poet and philosopher Édouard Glissant has called “the right to opacity.” To demand transparency—to insist that La Tercera confine itself to words that I share—would be to demand a kind of silencing, a reduction of the riotous complexity of Filipino expression to the fragment that happens in English. La Tercera expects a lot of non-Filipino readers, but the effort is profoundly rewarding, opening up a glorious new understanding of a country and a culture that ought to mean more to Americans than a twinge of guilty conscience. For a Filipino, I suspect reading it might just feel like coming home.

Pat Rodegast, Judith Stanton, Emmanuel’s Book: A Manual for Living Comfortably in the Cosmos

Ram Dass writes in his introduction to Emmanuel’s Book:

I first heard Emmanuel on WBAI in New York City. Actually, I heard Pat Rodegast reporting what Emmanuel was saying. She had been in contact for some time with this being whom she referred to as Emmanuel. She could contact him at will through meditative tuning and could hear him clearly though others around her could not. To each question asked by Lex Hixon, the host of the radio program, Pat relayed Emmanuel’s response. Listening to that radio show, what I was most struck by was Emmanuel’s charm and old-world courtliness, his humor, eloquence, directness, “hip’ness,” and the fact that his responses evoked intuitive trust in me.

Dass goes on to describe an interview with Pat/Emmanuel, stating,

As we settled in, Pat started a tape recorder so that I could have a record of our conversation. Pat started to describe colors which she saw as associated with me. In the middle of this description she said, “Emmanuel wants to say something. He is saying….” and then she reported Emmanuel’s comments about the colors, and we were off and running.

Joel Smith, Please Send Real Life: Ray Johnson Photographs

“Ray Johnson (1927–95) was a prankster and a contrarian who played at the outskirts of the art world,” writes Jean Dykstra in her review of this exhibition in The Brooklyn Rail.

After studying with Josef Albers at North Carolina’s Black Mountain College and moving to New York City, where he hung out with John Cage, Merce Cunningham, and the sculptor Richard Lippold, he seemed on the road to becoming an abstract painter. Instead, as Joel Smith puts it in his catalogue essay for Please Send to Real Life: Ray Johnson Photographs, “he became Ray Johnson.” He created modestly sized drawings and enigmatic, multi-media collages, which he called “moticos.” He became a mail-art pioneer, assembling an expansive network of correspondents who became the co-authors of his artworks. And in the last three years of his life, unbeknownst to most of his friends, he became a photographer.

Garielle Lutz, Backwardness: From Letters and Notebooks, 1973-2023

In an excerpt from Backwardness, Lutz describes intimacies with neighbors in her building. She writes that one woman

was perkily despondent and chesty, with hair pinned heavenward, and everything about her (she was just a dab of a woman, baleful and frail) was ruthlessly convenient. But what if the eye of the beholder was a troubled eye? She had been hollowed out by divorce. Some people get like that. They divert themselves from certain colorful sufferings to a wayside tendency to let things just slide. She had two sisters, but all three had filed out of the family a long time ago. Nobody talked. Her apartment (one bedroom) was full of husky furniture, collections, and a couple of stepladders. Her half of the conversation was always heavier on vows and pledges than on details of any completed deed. In those days, I always took people at their boosted self-estimation, so I believed her when she said there was still plenty of time for her to go back to school. (It would have been just high school.)

You can read the rest of the excerpt here.