The Annotated Nightstand: What Emerson Whitney is Reading Now and Next

Featuring Samuel R. Delany, Anne Boyer, and Morgan Tatly

Emerson Whitney’s first hybrid memoir, Heaven, circles largely around a question he poses relatively late in the book: “Who was mothered like they wanted to be?” What this includes is his relationship with his mother (flushed with love, fraught, downright toxic at times), his wonderful grandmother, as well as notions of femininity, womanhood, and what that all means when you’re a trans person.

Heaven is remarkable in how Whitney easily describes a situation from a child’s perspective (a coke addict looking for crumbs “the kind of guy who cared about carpet. I’d catch him on all fours, pulling particles out”) and a few pages later dip into the French theorist Luce Irigaray’s notions of “femininity” with such facility it all is clearly part of the same conversation.

Daddy Boy, Whitney’s memoir just published by McSweeney’s, like Heaven, looks closely at his past with family, particularly the fathers, and the impact on Whitney’s present. This is in conjunction with Whitney’s imploding marriage to a domme whom he calls “Daddy,” and Whitney’s decision to chase tornadoes as a means for escape.

Cameron Finch at The Rumpus writes, “Where Heaven interrogated femininity and motherhood, Whitney recalls the Daddy figures in Daddy Boy—his adoptive father, his biological dad, his dominatrix lover—who cut shapes throughout his life.” In an interview with Finch there, Whitney pins this down further: “Instead of defining the word Daddy, the hope is to take Daddy off of what we associate it with, which is man-ness. What could Daddy be? What is man-ness without Daddy?”

As in Heaven, Whitney continues to operate in a hybrid mode, including brief vignettes that, like a spell, make everything else fall away. The immediacy he conjures holds you still so you won’t miss anything. The subtle on- and off-ramps around these moments make it almost impossible to excerpt. As an example, at one point Whitney talks about his “favorite weather memories,” and describes about how power outages suddenly brought people together who otherwise were physically or emotionally absent.

He writes, “I remember my biological dad and I once playing with a Lite-Brite during a power outage. He was somewhere behind me and I was making those colored lights into a dog or something and then the power was out and he was suddenly there… Do you get what I’m saying? I fell in love with this feeling.”

Whitney tells us about his to-read pile, “Both of these are my recent must-reads that I gratefully picked up while out on book tour, a stack of luminaries, north stars! Two others are at home waiting for me.”

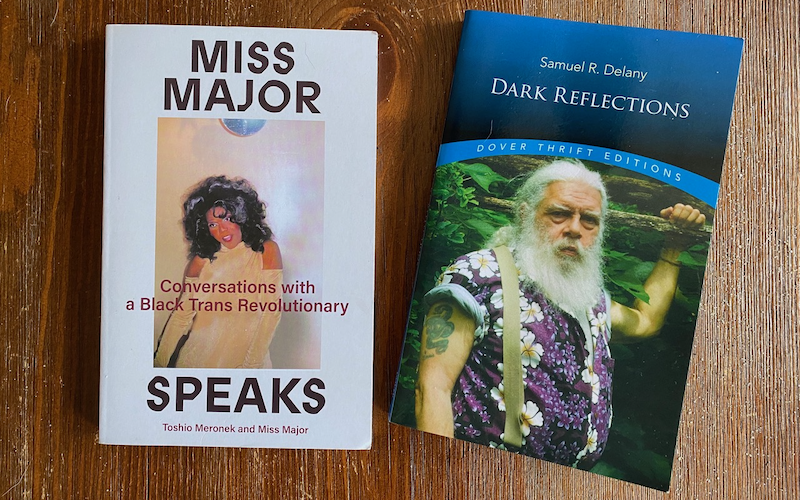

Miss Major Griffin-Gracy and Toshio Meronek, Miss Major Speaks: Conversations with a Black Trans Revolutionary

Miss Major Griffin-Gracy, as an 82-year-old Black trans woman, due to her identity alone, certainly has endured enough in life to share her story and wisdom as an elder in a community consistently attacked outright or harmed in more insidious ways. Griffin-Gracy, however, has also led a remarkable life of activism. While she has engaged in everything from grassroots organizing to HIV/AIDS healthcare, Griffin-Gracy focused her energy most explicitly on trans women of color who had been incarcerated (like herself).

The intersections between policing, incarceration, and trans identity are her primary focus. As she states, “from the moment we decide to be a transgendered person, [we] are living outside the law.” So it’s no surprise the anti-carceral legend Angela Davis provides some praise for this book. Davis writes, “The extraordinary insights in this book, always punctuated by Miss Major’s razor-sharp wit, allow us to understand how liberation movements for trans, queer and other routinely marginalized people can hold the most emancipatory potential for all.”

Samuel R. Delany, Dark Reflections

Delany is largely known as a Black sci-fi writer who has won the Nebula and Hugo Awards multiple times. He’s in the Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame. Dark Reflections, however, is a realistic story of a man who, if things had gone differently, may have been Delany’s life.

The protagonist, like Delany, is a Black gay writer living in New York in the 1950s. But he struggles to connect with the outside world and the people in it, and is terrified of his sexuality. Unlike Delany, he’s a poet—and one who gets marginal success. On Dark Reflections, Delany said in an interview, “I wanted to write a novel that young people seriously interested in writing might read, which would sketch something of the life awaiting them. Within that, I also wanted to make an aesthetic object that, in itself, would attempt to reflect some of the beauty one commits oneself to by going into the literary arts.”

Also, can I just say how much I love this cover? As a writer, I always am in awe of author photos that make a statement, capture the energy of the person, in what is often an awkward element of this whole writing circumstance. (Hilton Als has another I adore.) I look at such author photos and can only think: “goals.”

Morgan Talty, Night of The Living Rez

Talty’s amazing award-winning debut short story collection is in so many TBR piles, I think. And for good reason! Talty, in an interview with David Naimon, talked about many things, including how this describes lives of people who happen to be in an Indigenous population on a small island in Maine.

“This is a sliver of experience, an indigenous person’s experience on the Penobscot Nation,” Talty states. “From my own personal background, my own personal experience, this is the stuff I experienced, this is the stuff I saw, and of course, I’m going to write about it because I have a deep emotional connection to it. But I am never going to try to monopolize the Penobscot experience or try to say, ‘Oh, this is what it means to be Penobscot.’ My hope is that out of those 2,000-plus enrolled members, somebody else comes out with a book that’s completely counter to this one, almost like this book’s antithesis. Because the way I envision it is it’s almost like there’s this huge constellation of stories out there. The more stories we have, the more we have this great dialogue about what it means to be human… That’s what I hope happens. That’s what I want. I don’t want to be the only Penobscot writer getting a book reviewed in The New York Times. I want several. I want a dozen. I want all of these stories and experiences to be told.”

Anne Boyer, A Handbook of Disappointed Fate

The poet and Pulitzer Prize-winner for her memoir The Undying, Boyer’s 2018 essay collection A Handbook of Disappointed Fate attends to a series of concerns about aesthetics and poetry. Sam Huber has a thoughtful and thorough review/essay on A Handbook in n+1. Huber writes, “A Handbook of Disappointed Fate collects essays, fables, and speculative polemics written over the past decade, spanning Boyer’s trajectory from relative obscurity to relative celebrity… in Boyer’s hands the fable and the allegory are powerful conceptual tools, alternately diagnostic and prefigurative.

One way capitalism and patriarchy discipline their subjects is by shunting specific lives into predictable narratives, a dynamic that Handbook’s concluding essay terms ‘the law’s anxious categorization.’ A number of Boyer’s fables express this tendency of power to produce types: the exigencies of survival make lambs of the oppressed, for example, anonymous and herdlike, just as power’s predatory vantage turns the oppressor into a bird of prey.”

Diana Arterian

Diana Arterian is the author of the recent poetry collection Agrippina the Younger (Northwestern UP, 2025) and editor and co-translator of Smoke Drifts (World Poetry Books, 2025), a collection of Nadia Anjuman's poetry. A Poetry Editor at Noemi Press, Diana has received fellowships from the Banff Centre, Millay Arts, and Yaddo. She writes “The Annotated Nightstand” column at Lit Hub and lives in Los Angeles.