The Annotated Nightstand: What Diana Khoi Nguyen is Reading Now and Next

Featuring Jennifer Ackerman, jos charles, and Jenny Erpenbeck

A root fracture is when the root of a tooth has a fissure below the gum. It’s apparently excruciating. As one dental website put it: “Even a minor crack that one decides to leave untreated can lead to catastrophic results the longer the patient waits to seek professional treatment.” Perhaps this is why, Diana Khoi Nguyen tells us, “One morning, for the sake of my daughter’s life, I cut myself out of my mother’s life.”

While a more superficial reading may consider the “root fracture” to be her mother’s rage, Nguyen—tenderly, to this reader—gives a sense of the traumas and stresses of her parents that, while deep and experienced prior to Nguyen’s birth, impact the surface of their lives today. Or, as Nguyen succinctly puts it, “War: / an instrument whose sound is absorbed and amplified in the body of a girl / like mercury inside a fish.”

When reading Root Fractures, I thought again of the Athena Farrokhzad quotation I referenced when I wrote about Nguyen’s first collection, Ghost Of: “All families have their stories / but for them to emerge requires someone / with a particular will to disfigure” (tr. Jennifer Hayashida). Yet while Ghost Of is almost entirely focused on the terrible grief of losing a sibling to suicide and the inevitable existential questions regarding being in the wake of such a loss, Root Fractures gives more dimension to Nguyen’s family and their circumstances with similarly powerful images and language. Here, we get a sharper sense of the family dynamic—her brother’s depressive rage, her mother’s anger, her father’s quiet turning away—as well as the impact of the American-Vietnam War on her parents and their eventual migration.

In some of the most generous poems in the collection, Nguyen envisions their experiences, which include her mother doling out medicine as a child in the family pharmacy or her father riding the bus home from Pasadena City College after a late shift. At one point Nguyen writes, “I am trying to remember the details, but this is not my memory.” Her probing, despite the memories not being her own, is, it seems, to further understand the current state of things as well as understand her inherited traumas.

In one poem, she puts forth a dozen or so potential alternate timelines for her mother: she never leaves Vietnam, continues school, becomes a pharmacist, has children, has one child, doesn’t have any. As with Ghost Of, in Root Fractures Nguyen doctors family photographs in order to continue to interrogate notions of the family archive and what it means when one of its members excises himself out (as Nguyen’s brother, physically, did not long before his death). Yet, here, she pushes further. Rather than solely filling in figures with text or the space around them as she had in her first collection, at times Nguyen makes she and her family disappear entirely into the landscape—a “what if?” of their familial pain never happening at all.

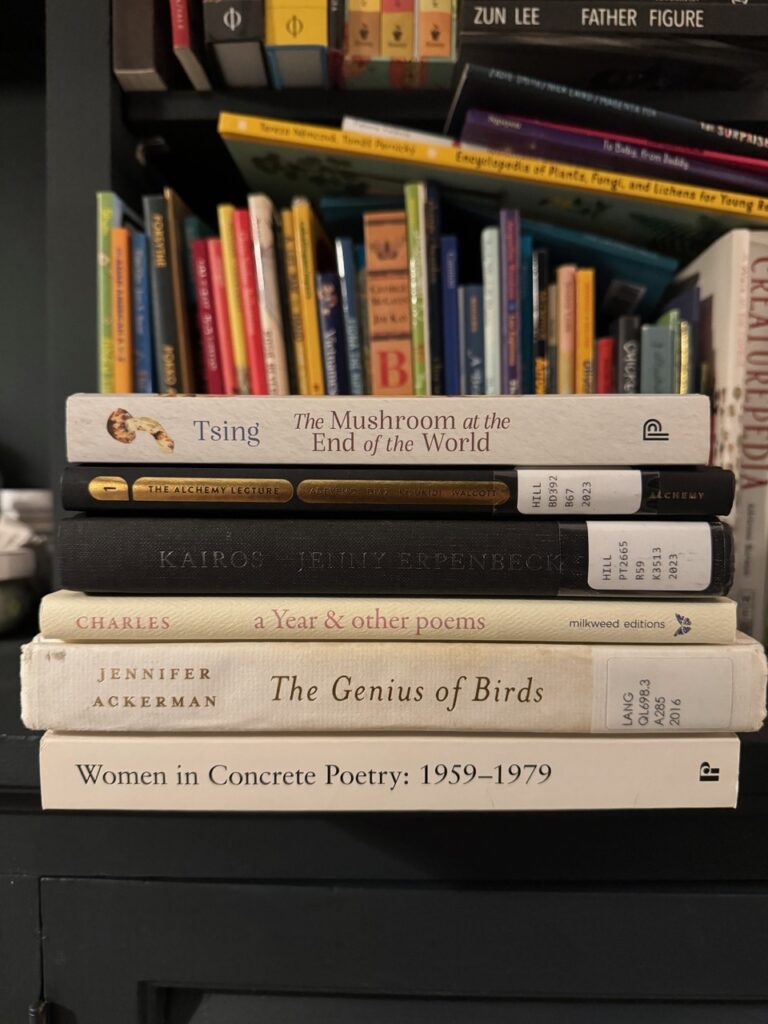

Nguyen generously tells us about her to-read pile: “It’s a mixed pile of works I’m encountering for the first time, rereading, or purposefully savoring so as to extend the exquisiteness of each page.

A fellow faculty member I met while on a panel for our university’s AAPI undergraduate student org brought this Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, collection to my attention, and am continuously nourished by its application of the matsutake mushroom as a metaphor for what grows amid ruin. Not to mention how it fuels my passionately-burning and burgeoning mycology obsession.

And speaking of mycelium, The Alchemy Lecture: Borders, Human Itineraries, And All Our Relation—entangle the minds of a philosopher, architect, poet (Natalie Diaz), and cultural theorist on the topic of living in this present moment (and our planet’s future).

No one asked, but I’ve been slowly plugging away at research for a craft book on visual poetics and can’t get enough of this Women in Concrete Poetry: 1959 – 1979! Some pages in here rival the kaleidoscopic geometries of diatoms.

And last but not least, the Js: Jennifer Ackerman is a genius in how she sees and considers our avian friends via The Genius of Birds, jos charles’s a Year & other poems is a steady comfort for my despair—it assuages by not looking away from current disasters, but by existing amid them with much tenderness. And my favorite living writer, Jenny Erpenbeck, is one whose sentences seduce, whose plot takes captive my heart—Kairos is astonishing in the small doses I permit myself. I’d read Erpenbeck’s previous novels via Susan Bernofsky’s translation, but am meeting Erpenbeck in new intimate ways through this Michael Hoffman translation.

*

Alex Balgiu and Mónica de la Torre eds., Women in Concrete Poetry: 1959 – 1979

Theadora Walsh in Los Angeles Review of Books says of this important book, “In the anthology, co-editors Alex Balgiu and Mónica de la Torre cast a porous net to gather 50 artists, poets, performance artists, writers, and activists affiliated with concrete poetry…The importance of preserving visual components of concrete poems explains why the anthology often reads more like an exhibition catalog than a collection of poetry. The attention to materiality and presentation represents a new approach to the poetry anthology. Much like the concrete poem liberates words from traditional expectations of language, the anthology commits to releasing individual poems from the limitations of traditional anthologies.”

Jennifer Ackerman, The Genius of Birds

Ackerman’s bestselling book provides exactly what its title suggests: each chapter attends to a bird and their particular brilliance likely otherwise unknown to the reader. As Jennifer Hackett in Scientific American writes, “Science journalist Ackerman sets out to show that being called a ‘birdbrain’ should be a compliment, not an insult. Birds’ clever social and environmental problem-solving skills, she shows, establish them among the most intelligent members of the animal kingdom. Crows frequently steal the show: for example, they craft tools, such as branching twigs perfectly pruned into solitary sticks that can retrieve meat from plastic tubes. Even birdsong is cause for admiration: some birds’ ability to hear a sound and re-create it has much in common with our own capacity to learn language.”

Dele Adeyemo, Natalie Diaz, Nadia Yala Kisukidi, Rinaldo Walcott, Borders, Human Itineraries, and All Our Relation (ed. Christina Sharpe)

The beloved and brilliant Christina Sharpe has begun a series for Duke University Press called “The Alchemy Lecture,” which documents a now-annual event at York University, where Sharpe is a professor. At The Alchemy Lecture, four thinkers of different experiences and métiers come together and hash out what is most important to them.

The next book involves Phoebe Boswell, Saidiya Hartman, Janaína Oliveira, Joseph M. Pierce, and Cristina Rivera Garza. This is definitely a series to keep an eye on. The jacket copy for this book states, “The first annual Alchemy Lecture brings four deep and agile writers from different geographies and disciplines into vibrant conversation on a topic of urgent relevance: humans and borders. Borders, Human Itineraries, and All Our Relation captures and expands those conversations in insightful, passionate ways.”

jos charles, a Year & other poems

In the Publishers Weekly review of a Year & other poems, they write, “The luminous latest from Charles (feeld) unfolds in a series of short lyrics over the course of a year, holding time’s progression in a delicate balance with a changing self. These carefully constructed poems are organized by their forms, with titles like ‘A Note,’ ‘A New York Poem,’ ‘A Song,’ ‘A Fantasy,’ and of course ‘A Year.’ While Charles’s previous books were informed by the diction of social media (Safe Space) and of old English (feeld), this latest casts more widely, and privately, for its idiom, finding it in the poem itself: ‘I put you into a poem/ You climbed the giantest tree’ and ‘We speak/ a language capable of itself.’ Like Paul Celan, whom the collection notes as a touchstone, readers are asked to wade into the idiosyncratic language of another’s mind, and to be transformed by it.”

Jenny Erpenbeck, Kairos (tr. Michael Hofmann)

“To witness someone else’s tears is not necessarily to be moved yourself. But to absorb ‘Kairos’ is — like reading ‘Wuthering Heights’ or ‘On Chesil Beach,’ listening to albums like Lou Reed’s ‘Berlin’ or Tracey Thorn’s ‘A Distant Shore,’ watching the film ‘Truly, Madly, Deeply’ or ingesting an ideal edible — to set yourself on a gentle downward trajectory,” writes Dwight Garner in his New York Times review. “If ‘Kairos’ were only a tear-jerker, there might not be much more to say about it. But Erpenbeck, a German writer born in 1967 whose work has come sharply to the attention of English-language readers over the past decade, is among the most sophisticated and powerful novelists we have. Clinging to the undercarriage of her sentences, like fugitives, are intimations of Germany’s politics, history and cultural memory. It’s no surprise that she is already bruited as a future Nobelist.”

Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins

This book is beloved by many for its deep investigations of capitalism, environmental ruin, invisible labor, and how nature can and will persevere in spite of us long after we’re gone. Do you need more of an endorsement than from the inimitable Ursula K. Le Guin? She says of the book, “Scientists and artists know that the way to handle an immense topic is often through close attention to a small aspect of it, revealing the whole through the part. In the shape of a finch’s beak we can see all of evolution.

So through close, indeed loving, attention to a certain fascinating mushroom, the matsutake, Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing discusses how the whole immense crisis of ecology came about and why it continues. Critical of simplistic reductionism, she offers clear analysis, and in place of panicked reaction considers possibilities of rational, humane, resourceful behavior. In a situation where urgency and enormity can overwhelm the mind, she gives us a real way to think about it. I’m very grateful to have this book as a guide through the coming years.”