The Annotated Nightstand: What Catherine Chen is Reading Now and Next

Featuring Sarah Aldridge, David Wojnarowicz, and More

While I don’t have this technology in my home, so often I visit friends and hear “Hey, Alexa,” followed by some relatively basic command to play a song or album. The AI associated with the Amazon Echo allows it to listen for this cue (to which it responds in the often-feminine voice) and deliver data people request. Poet and performer Catherine Chen once transcribed data for the Echo and thus has had a good amount of time to meditate on technology, its trajectory. In an interview from a few years ago, Chen explains, “Every poem is a negotiation of self, the lyric I. In my understanding, the lyric I feels very far away from who I actually am and the poem is the lyric attempt to process this distance. Do I approach this self? Do I leave it alone? Do we awkwardly ignore each other? A poem offers a model for reconciling distance and tension in ways that I see as generative.”

Chen’s recently published debut collection Beautiful Machine Woman Language was published by Noemi Press, for which I am a Poetry Editor (I didn’t work on this manuscript). At one point in Beautiful Machine Woman Language, Chen writes, “Every technology reflects the desires of its creator.” We’ve seen this in films such as Her (though, arguably, not as insightfully), Ex Machina (pointedly). Often the creator’s desire is connected to feminine characteristics. This can hardly be a surprise considering the position women often hold and have held in the majority of the world—caretaker, doer of nettling tasks. The poems chronicle an unnamed data worker (“I was responsible for helping organize the oral archives of voice recognition technology”) falling in love with the femme AI people talk to—these are the utterances they are meant to catalog. As Chen writes of the AI, “Sometimes her worth is condensed to the size of ‘You are dumb.’ ‘You’re welcome slut.’” Even if it is “just a robot,” why treat it with cruelty? Where and when else have we had that impulse as creatures? Has it ever been a good one? Douglas Kearney says of the debut poetry collection, “Beautiful Machine Woman Language is the crash site of individual and empire, the smoke still twisting before the poet’s eyes; fire deep in their throat.”

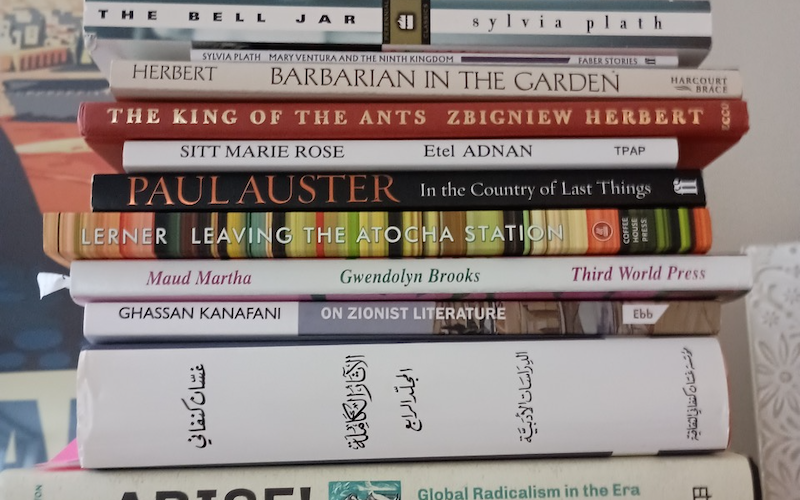

Regarding their to-read pile, Chen tells us, “Mythic landscapes lying horizontal: what system is buried here.”

The Classic of Mountain and Seas / Shanhai jing

If you love a literary squabble, how about a book that’s been around for 2400 years, give or take, and people are still arguing over who wrote it? Sima Qian, the “father of Chinese historiography” from the 2nd and 1st centuries bce, started the debate—and it’s never stopped. It’s a text that, because of its age alone, has had many different hands in its existence over time. The illustration of a phoenix was colored in during the Qing Dynasty (between the 17th to early 20th centuries). Overall, The Classic of Mountain and Seas / Shanhai jing attends to a wide variety of concerns, largely the geographical, natural, medicinal, religious, and mythical. The landscape of mountains and water are given equal attention as Nüwa and Nine-Tailed Fox.

Ronaldo V. Wilson, Virgil Kills: Stories

Roberto Tejada says of Wilson’s collection of stories, “A novel, a dream book, a study in self-formation, a concert of surface, sex, and underswell…. Ronaldo Wilson’s ingenious Virgil Kills guides us, in the style of collage and choreography, through a netherworld where the “the act of the body in the turns of its written emissions” can connect memory to the real and the fictive. Wilson’s portrait of Virgil—mixed-media invention; composite persona—is in equal parts riotous and intimate. In scenes of sexual acts, social kinship, family attachments, and racial marking; in narratives of loss, defiance, escape, and exile, Wilson refutes ‘sorrow as the route to freedom,’ defining what it means instead to render ‘temperature and thought’—that is, to amaze, abrogate, and amplify the attributes of embodied life.”

Sarah Aldridge, Tottie: A Tale of the Sixties

Sarah Aldridge is the pen name for Anyda Marchant. Her legal name was Anne Nelson Yarborough De Armond Marchant—she began to use its acronym for her name. Marchant’s life is a wild one, and I highly recommend diving into this article on her if you’re inclined. She was of first women in the US to pass the Bar Exam in 1933. Not only did she practice law and have a celebrated career for 40 years, she reached high positions of power including in the Law Library of Congress. She attained a particularly choice post when the man who held it was drafted during WWII. When he returned and resumed his job, rather than settle for a lower position, Marchant left the Law Library of Congress. She met her life partner Muriel Inez Crawford while practicing in 1947 at a time when the hint of homosexuality could destroy one’s life thanks to McCarthy. They remained closeted for 40 years, until Marchant publicly came out in 1990. In 1973, Marchant, Crawford (Marchant’s partner), Donna McBride, and Barbara Grier founded Naiad Press for lesbian literature. Naiad published Marchant’s novel The Latecomer under her pen name Sarah Aldridge—largely considered the first lesbian romance novel that ends happily (it was published in 1974). The jacket copy for Tottie reads like a description from Marchant’s life: “Connie Norton is 27, an associate in a good law firm, and scheduled to marry an arrogant young man who bores her without her quite realizing why. She meets Tottie, a young runaway from a wealthy family, who is apparently involved with violent student activists.”

David Wojnarowicz, Memories that Smell Like Gasoline

Wojnarowicz is largely known for his paintings and art practices, as well as his AIDS activism. He writes, “It is exhausting, living in a population where people don’t speak up if what they witness doesn’t directly threaten them.” His writing and art feel no less urgent today, decades later, considering the exponential legislation and threats against queer people in the United States. There was an event at the Whitney from 2018 to highlight Wojnarowicz’s work that you can access here. As the site states, “Organized in collaboration with Visual AIDS, this evening devoted to Wojnarowicz’s written work includes readings and performances by artists who were engaged with Wojnarowicz during his lifetime, or who have been inspired by his example. Taking its title from his final collection of stories Memories That Smell Like Gasoline (1992), this program highlights the passion and rage of Wojnarowicz’s singular voice.”

Charles Chace, Fleshing Out the Bones: Case Histories in the Practice of Chinese Medicine

Chace began studying acupuncture in the mid-1980s and continues to take seminars on classical Chinese language and thought to gain greater knowledge on pre-modern Chinese medical texts. I was able to locate an interview with Chace (aka Chip). Some of those questions and answers are particular to acupuncture specialists, but I appreciated Chace’s answer to the question “What do you do if your prescription doesn’t work?” Chace states, “If what you prescribe doesn’t work, or makes the patient worse, that should tell you something about the diagnosis. You have to ask yourself, ‘why didn’t that work?’ You should be able to retrieve some piece of information that points to a positive outcome. It’s inevitable that you will make diagnostic mistakes, and you should use those mistakes to your advantage in a systematic sort of way. What doesn’t work should be as informative as what does work.”

Robert Ford Campany, Strange Writing: Anomaly Accounts in Early Medieval China

The jacket copy for this book states, “Between the Han dynasty, founded in 206 B.C.E., and the Sui, which ended in 618 C.E., Chinese authors wrote many thousands of short textual items, each of which narrated or described some phenomenon deemed ‘strange.’ Most items told of encounters between humans and various denizens of the spirit-world, or of the miraculous feats of masters of esoteric arts; some described the wonders of exotic lands, or transmitted fragments of ancient mythology. This genre of writing came to be known as zhiguai (‘accounts of anomalies’).” In an academic review of this book, Stephen F. Teiser writes, “Anomaly accounts (zhiguai) are tales written in literary Chinese that relate the appearance of category-busters such as pygmies and giants, fishes shaped like oxen, weeping icons, dragons, immortals, the dead returned to life, elusive jade maidens, and ferns that turn into worms. First recorded perhaps as early as the third century B.C.E., these narratives continued to be written until recent centuries.”

Diana Arterian

Diana Arterian is the author of the recent poetry collection Agrippina the Younger (Northwestern UP, 2025) and editor and co-translator of Smoke Drifts (World Poetry Books, 2025), a collection of Nadia Anjuman's poetry. A Poetry Editor at Noemi Press, Diana has received fellowships from the Banff Centre, Millay Arts, and Yaddo. She writes “The Annotated Nightstand” column at Lit Hub and lives in Los Angeles.