The Annotated Nightstand: What Alison Bechdel Is Reading Now, and Next

Featuring Sarah Schulman, Urvashi Vaid, Joan Didion, and Others

Alison Bechdel is perhaps most famous for (among other things) her comic memoir Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic, which scrutinizes her memories of childhood alongside revelations of the present. Her father’s likely suicide not long after Bechdel came out in college leads to information about her father’s queerness and his run-ins with the law when trying to seduce teenaged boys.

While Bechdel has drawn/written other beloved books (Are You My Mother?, The Secret to Superhuman Strength), her hit weekly comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For, with its twenty-five-year run, is her most enduring project. (Bechdel, inspired in part by Viriginia Woolf, famously quotes a friend in the comic, which spurred the often-cited “Bechdel test.”) DTWOF gave shape to the varied quotidian lives of lesbians living in a city, with Mo Testa as a stand-in for Bechdel, endlessly stressed out by the political strife of the world and her love interests (or lack thereof).

In Spent, we get to dip in on the lives of some of the recurring characters from DTWOF, with Alison and her partner Holly as the central figures around whom dramas swirl. If Bechdel called DTWOF “half op-ed column and half endless serialized Victorian novel,” we catch up with the crew as they contend with the often-determinate experiences of middle age with wide-eyed interest.

As in DTWOF, our protagonist struggles with the crushing realities of our modern oppressions (the book begins in the first Trump presidency and runs up toward the second) while aiming to scratch out a comfortable living, hold onto love, have a sense of artistic purpose, and square internal politics with action. “How can the world keep getting worse and worse without actually ending?” Alison asks at one point. “Is it some corollary of Zeno’s Paradox?”

Alison and her happy-go-lucky partner Holly manage rural Vermont property where they run a goat sanctuary. While the Alison of Spent didn’t write Fun Home, she did write Death and Taxidermy, a book of a similar narrative—taxidermist father instead of undertaker, sister instead of two brothers.

Death and Taxidermy is similarly a runaway success, in this case with an award-winning television adaptation (Fun Home has a wildly successful musical). Spent’s Alison feels she has little claim to the television show’s plot or achievements, and certainly not much of the money—she and Holly often have to tighten their belts.

Then, like Charlie Kaufman’s Adaptation, things begin to spin out. Holly, good with tools and with a small social media following of her doing different types of impressive manual labor, is suddenly thrown into the deep end of internet fame with a viral video. Alison is supposed to finish her next book, $um (get it?), and quick—she sold it to an uber-capitalist publisher.

But “Who can draw when the world is burning?” she asks herself. (She quickly gets distracted by the idea to make a television show of her own, even flying out to Hollywood to try to make it work.) Both Alison and Holly are forced to contend with fame’s pitfalls alongside its often superficial periodic wins.

Throughout the book, Bechdel doggedly asks: on the gradient of heeding current trends and challenges of modern life, at what point does one “sell out?” (Blessedly, in life and page, she doesn’t.)

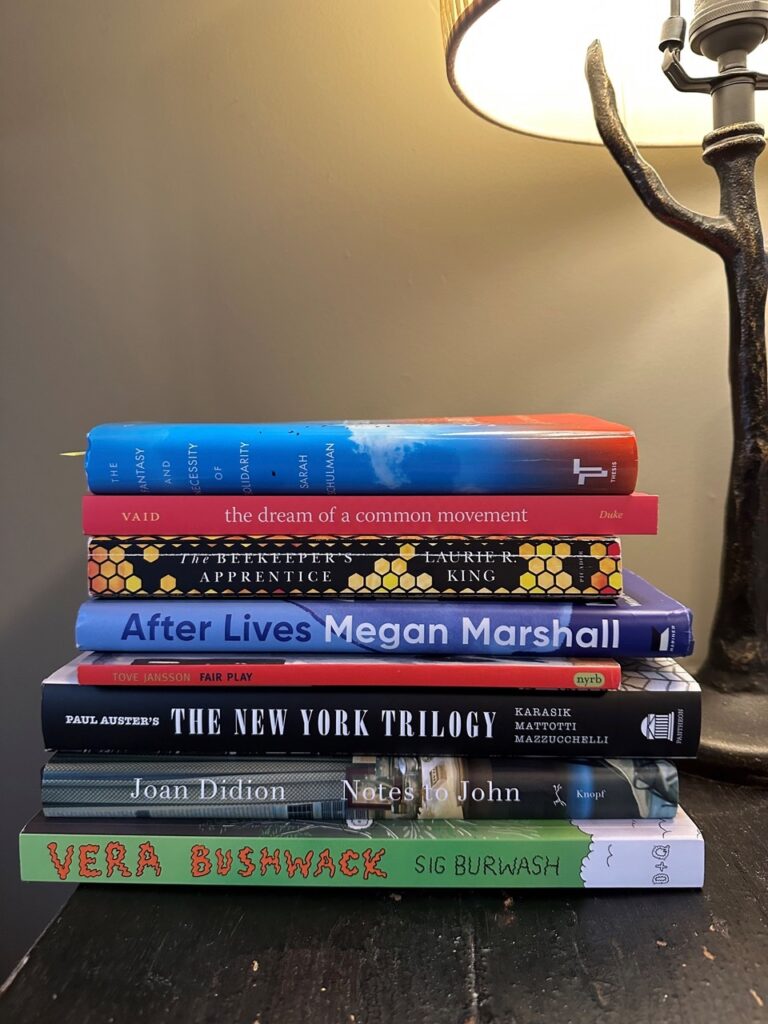

Bechdel tells us about her to-read pile,

My stack is a mix of books that serve as guides to the political moment (Schulman, and the late Urvashi Vaid with their maps for coalition-building), and books that offer enough escapism from the fascist onslaught to allow me to sleep at night (Tove Jansson’s portrait of life with her partner Tooti on their tiny island in the Gulf of Finland, Sig Burwash’s nonbinary protagonist building a cabin in the wilderness of Nova Scotia, Laurie King’s surprising riff on Conan Doyle.)

In between are Megan Marshall’s exquisite meditation on the art of biography, the recently completed graphic adaptation of Auster’s New York Trilogy, and Didion’s “latest,” about which I feel conflicted—but so far my curiosity seems to have won out over my ethical qualms.

*

Sarah Schulman, The Fantasy and Necessity of Solidarity

“It is true that there are a lot of cowards,” Schulman tells Lydia Polgreen in an interview at the New York Times about her new book. Schulman goes on,

I start the book with a quote from Haddi Shafi, who is a Palestinian lesbian leader, and she says: Think about what you can do, not what you can lose. That is my mantra because as I’ve been going through the world, I’m constantly engaging people who are terrified that they’re going to lose some status, they’re going lose some access—and often they do. But you get something else, which is this internal coherence of integrity.

Urvashi Vaid, The Dream of a Common Movement

Judith Butler says of this collection:

In this final, moving book by Urvashi Vaid, we find the history of a movement for radical justice, equality, and freedom embodied in the life of one of the most persistent, influential, and brilliant activists and leaders. Vaid tells her own story by documenting the formation of her politics and her youthful but prescient feminism and defense of lesbian and gay rights.

Laurie R. King, The Beekeeper’s Apprentice or, On the Segregation of the Queen

The jacket copy for this twentieth anniversary reprinting reads:

In 1915, Sherlock Holmes is retired and quietly engaged in the study of honeybees in Sussex when a young woman literally stumbles onto him on the Sussex Downs. Fifteen years old, gawky, egotistical, and recently orphaned, the young Mary Russell displays an intellect to impress even Sherlock Holmes.

Megan Marshall, After Lives: On Biography and the Mysteries of the Human Heart

A New Yorker “briefly noted” review says of this book,

Marshall, a Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer, turns inward, reflecting on her discovery of old personal paraphernalia, including letters and photographs. She writes of her grandfather, Joe Marshall, who oversaw photography and film for the American Expeditionary Forces during the First World War, and of Jonathan Jackson, a Black high-school classmate, who was killed at seventeen when he tried to free his older brother, a Black Power activist, from prison.

Tove Jansson, Fair Play (trans. Thomas Teal)

In their starred review, Booklist writes of Fair Play,

In this brilliantly translated novel from the Swedish by Thomas Teal, Finnish-born author Tove Jansson, whose Moomin children’s books may be familiar to some readers, gives us a spare, rich collection of vignettes. A novel, a short-story collection, and an autobiographical journey, Fair Play centers on the lives of two creative women—Mari, the writer, and Jonna, the artist.

Paul Karasik, Lorenzo Mattotti, David Mazzucchelli, Paul Auster’s The New York Trilogy: City of Glass, Ghosts, The Locked Room

Library Journal gives this graphic novel adaptation of Paul Auster’s “New York Trilogy” a starred review. Tom Batten gives it this verdict: “An immersive and innovative adaptation, blending exhilaratingly experimental storytelling, tropes and an atmosphere drawn from the noir genre, metafiction, and philosophical musings about art and identity.”

Joan Didion, Notes to John

Bechdel’s ethical concerns about the recently published posthumous book from Didion is perhaps captured in its description as her journals to her husband describing her experiences in psychiatric sessions. “It’s odd to be reviewing a book by a complex writer, whose work I have engaged so deeply with, that I don’t think counts as part of her oeuvre,” writes Lara Feigel at The Guardian.

Yet, of course, Bechdel isn’t the only curious one—it was an “Instant New York Times Bestseller.”

Sig Burwash, Vera Bushwack

The beloved Kate Beaton says of this new book:

Vera Bushwack is a perfectly fully formed comics debut, like Athena from the head of Zeus….When the rigid panel grid gives way, it is most likely to explode into furious figures on bucking horses, or of quiet emotion enveloped in the protection of nature. And it is a story with a lot of those feelings to sift through, sit with, or chainsaw apart (if you will). I hope it is the first of many books we see from Sig Burwash.

Diana Arterian

Diana Arterian is the author of the recent poetry collection Agrippina the Younger (Northwestern UP, 2025) and editor and co-translator of Smoke Drifts (World Poetry Books, 2025), a collection of Nadia Anjuman's poetry. A Poetry Editor at Noemi Press, Diana has received fellowships from the Banff Centre, Millay Arts, and Yaddo. She writes “The Annotated Nightstand” column at Lit Hub and lives in Los Angeles.