The Annotated Nightstand: What Aisha Sabatini Sloan Is Reading Now and Next

Featuring Eve Babitz, Renee Gladman, Nicolette Polek, and More

As an essay collection, it should be no surprise that Dreaming of Ramadi in Detroit attends to topics that are simultaneously varied and interconnected. Throughout each, Sloan has a topic—a piece of art, a historical event—around which her mind and language whirls. Quite often, understandably, what dictates much of her inquiry is the precarity of Black life, art, and joy due to the consistent violences, large and small, Black Americans experience in this country.

What makes Sloan’s writing and mind remarkable, though, is her need to complicate the obvious us vs. them. As a woman with a Black father and Italian-American mother, both of whom she loves dearly, it’s likely that dichotomy never felt possible. In one essay, the longest in the collection, Sloan describes doing a ride-along with her cousin—a police officer in Detroit—a woman with whom she is close. Before Sloan gets in too deep, she describes her uncertainty in sharing the essay because it may compound the stereotypes about Detroit, a city Sloan adores, as a place of violence.

“But censoring trouble doesn’t make it go away,” she writes. “James Baldwin and the Buddhists have long argued that healing results only from staring struggle straight in the face.” During her shift, Sloan’s cousin illustrates her engagement with her job as mostly “[t]he capacity to listen and observe more than bully and corral”—one that goes counter to the general idea among radical liberals about how police police.

Not many pages later, in the titular essay, Sloan describes how, years later, she has “developed an instinctive sense of terror upon seeing police cars.” This is largely because of the scalding footage of white police officers killing Black men, which is increasingly available with such promiscuity it compounds Sloan’s fear and a growing hostility for American police officers. While this description isn’t unique, that doesn’t make it any less meaningful.

But her next gesture is what makes Sloan’s writing remarkable. She asks, “And aren’t I? Affiliated? My cousin is my cousin. She’s my blood. But so am I Black. My father is Black. She’s white. But her children are Black. Our affiliations are bleeding all over the place.” The messiness of life defines so much of these essays, as Sloan shows time and again how, despite how much as we might want it otherwise, we are all connected and in each other’s business. The idea of the silo, ultimately, is impossible.

This edition of Dreaming of Ramadi in Detroit is a revision of a collection that originally came out in 2017. So much has happened since, and it is a testament to Sloan’s capacity as a writer and thinker to integrate some of the events and their impact on her thinking so seamlessly. Rather than create a sense that her feelings haven’t evolved, it underscores the nimbleness and sharpness of Sloan’s mind. She’s not interested in providing answers to these impossible problems that have been centuries in the making but, instead, “staring struggle straight in the face.”

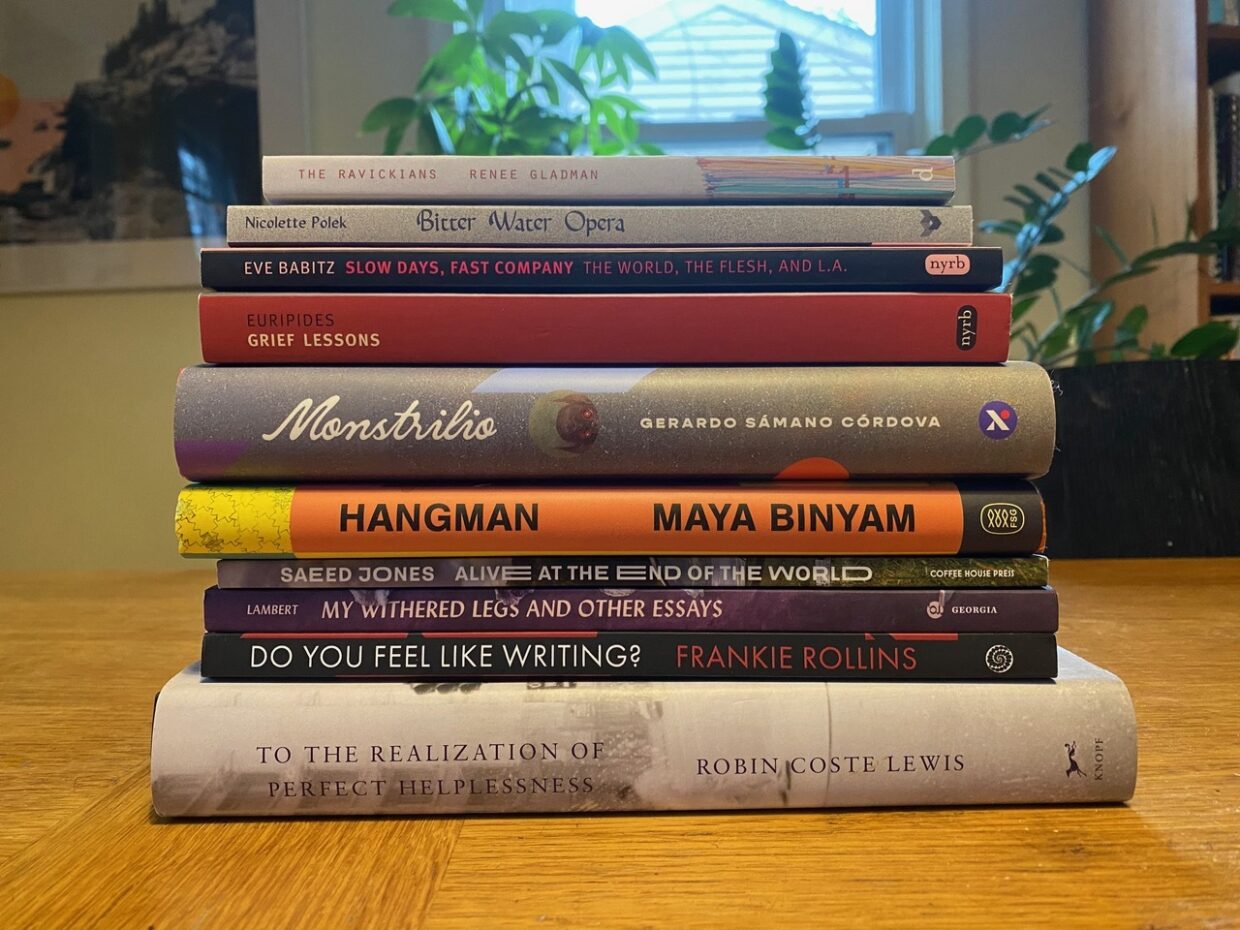

Sloan tells us about her to-read pile, “This stack consists of books that came to me from unexpected, hawk-like sources. Some were written by people who radiate joy as a form of intelligence. Some were written by people who strike a particular kind of chord in my heart. Some were written by people who write about fake countries, ancient feelings, or Los Angeles.”

*

Renee Gladman, The Ravickians: A Novel

This is the second in a four-novel Ravickian series by Gladman. In an interview with Zach Friedman at BOMB, Gladman explains: I definitely would prefer social science fiction to science fiction, as I really didn’t intend these books to ask deep questions about technology or bioengineering or inter-galaxy relations. Instead, they wonder about city living, architecture, language and communication, desire, and community—the same things I wonder about in my own life…. I guess my resistance is that I don’t know what people mean when they say sci-fi, what it is they wish to qualify.

Maybe EF [Event Factory, the first Ravickian novel] is sci-fi because a black lesbian poet wrote it. That’s pretty otherworldly. My concern, the more I think about this, is that “sci-fi” or “fantasy” are applied to assuage the deep confusion and disorientation experienced by the characters of the two books EF and The Ravickians or to justify why someone might have to do a backbend in order to eat. For me, it needs to stay on this side of reality, and it needs to be pushing for physical space in this world.

Nicolette Polek, Bitter Water Opera: A Novel

Gia, a heartbroken and unmoored protagonist, writes a letter to Marta Becket, a not-fiction artist, actor, and dancer. A week after putting it in the mail, Marta arrives at Gia’s house. Kirkus Review writes of Bitter Water Opera, Polek creates striking, high-contrast images of each place Gia floats, half-tethered to her worldly connections and responsibilities. Though she has one eye trained on ‘the despairing antipossibility of [her] past’ and one on ‘the possible despair in [her] future,’ her narration burnishes each thing she encounters, collects, considers, and leaves to rot in her present… Gia stumbles into healing like a fawn, but her breathtaking sensitivity makes this rebirth story worthwhile. As all quotations and biographical details attributed to Marta are genuine, the novel also acts as an introduction to the life of a fascinating artist.

Eve Babitz, Slow Days, Fast Company: The World, the Flesh, and L.A.

I feel like nothing can really beat this jacket copy: No one burned hotter than Eve Babitz. Possessing skin that radiated ‘its own kind of moral laws,’ spectacular teeth, and a figure that was the stuff of legend, she seduced seemingly everyone who was anyone in Los Angeles for a long stretch of the 1960s and ’70s. One man proved elusive, however, and so Babitz did what she did best, she wrote him a book.

Slow Days, Fast Company is a full-fledged and full-bodied evocation of a bygone Southern California that far exceeds its mash-note premise. In ten sun-baked, Santa Ana wind–swept sketches, Babitz re-creates a Los Angeles of movie stars distraught over their success, socialites on three-day drug binges holed up in the Chateau Marmont, soap-opera actors worried that tomorrow’s script will kill them off, Italian femmes fatales even more fatal than Babitz.

Euripides, Grief Lessons (trans. Anne Carson)

Tim Rutten in the Los Angeles Times writes of this translation, [Carson] has provided each of the plays with brief but provocative introductions that stand as sort of keys to her intentions and suggestions about these classic plays’ continuing claims on our attention. The introduction to “Herakles,” for example, would be worthwhile reading simply to come on this literary apothegm concerning the choral function. “One of the functions of the tragic chorus is to reflect on the action of the play and try to assign it some meaning. They typically turn to the past in their search for the meaning of the present—scanning history and myth for a precedent. It was Homer who suggested we stand in time with our backs to the future, face to the past. What if a man turns around? Then the chorus will necessarily fall silent. This story has not happened before.”

Gerardo Sámano Córdova, Monstrilio

Colin Chappell at Library Review writes of Sámano Córdova’s debut Monstrilio, The novel opens just moments after a young couple has lost their only son Santiago, his small body folded between them in his tiny bed. In an act of grief or love or desperation, Magos, the boy’s mother, carves out a piece of his lung, places it in a jar, and begins to feed it. This being a horror novel, of course, this doesn’t go well, and eventually the hungers and desires and thingness of what results must be reckoned with. How Magos and her husband Joseph reckon with monstrilio provides the emotional thrust of the story, which is told from four perspectives across the urban landscapes of Brooklyn, Berlin, and Mexico City. Córdova asks the reader to consider the limits of familial love and understanding. He provides no easy answers, and readers may find themselves touched and horrified in equal measure.

Maya Binyam, Hangman: A Novel

Named one of the best books of 2023 in Vulture, Tope Folarin writes there, Most immigrant novels of recent vintage share a single plot: a bright and hopeful person from the global south travels to a rich country in the global north and discovers that reality does not resemble their dreams. Maya Binyam’s Hangman immediately upends expectations by moving in the opposite direction—away from the adopted country and back toward the abandoned one.

Hangman upends expectations in other ways as well—Binyam withholds details that feature prominently in most immigrant tales, like the name of the country her protagonist comes from and the name of the country where he lives. Binyam’s tale, instead, foregrounds absence, and invites us to fill in the gaps that recur throughout the novel. In so doing, she is inviting us to question our expectations about these kinds of stories, and to contemplate the possibility that the varied lives of immigrants the world over cannot be rendered effectively in narrative cliches. This is a bold, courageous, and resonant book.

Saeed Jones, Alive at the End of the World

A poetry collection that landed on about a dozen “Best Books of 2022” lists from NPR to the American Library Association to The New Yorker, this is still on my list to procure! Erin Overby, The New Yorker archive editor, wrote on Jones’ poem “A Stranger” in a newsletter: In 2020, The New Yorker published “A Stranger,” a poem by Jones about his mother, who died in 2011. The verse is short but ravishing—a compressed catechism of bereavement….

Jones unravels and reconfigures language like he’s untying a knot, then rethreads the strands in a delicate new construction. The verse is haunting, yet its focus remains on the living—those left behind, whether unmoored by their sorrow or resolutely, even avidly, continuing to reaffirm their own existence. Jones writes in the space between wreckage and resilience. He offers a calibrated reckoning with his own grief, cradled in ambiguity—and we wait, holding our breath, to see what is tendered next.

Sandra Gail Lambert, My Withered Legs and Other Essays

In an essay, Lambert describes a “thinly disguised fiction” short story that “explored themes of independence and isolation, of disability and desire. The woman used a wheelchair. She was a lesbian.” This story received a great deal of criticism. Lambert writes in The Paris Review that after her decision to write nonfiction, “people were somewhat less likely to tell me I was wrong about my own life.” She goes on, saying: But the obsession with my legs continues….Why would I think about my legs all the time? Sometimes my legs are a part of the story, so a legitimate point can be made that I should write more about them. But then the next sentence of the critique will offer up examples of how I can do that.

Useless continues to be a frequent descriptor offered. Other suggestions have included atrophied, flabby, and withered. The next paragraph of feedback is often something about how these omissions are signs that I’m not delving enough into my life, that I should “dig deeper,” that I’m not writing in as honest a way as I could. I can deal with ignorant and disrespectful words, but now I’m being told I’m a dishonest writer. Fuck you, I think.

Frankie Rollins, Do You Feel Like Writing?: A Creative Guide to Artistic Confidence

In an essay for University of Arizona The Poetry Center, Rollins writes of her experiences writing poetry in her twenties: [P]oetry humanized us. Made it okay to be broke, okay to live in a lousy apartment complex, okay to come from troubled families, okay to dream that someday we would write something meaningful, something beautiful, something that would lift us into our next incarnations of self. Early on, my poet mentors were female. Jean Valentine, Lucille Clifton, Sylvia Plath, Audre Lorde, and Margaret Atwood.

I needed these poets to tell me how to live a life that wasn’t the traditional American dream. Raised in Virginia, in a culture (at the time) with exacting requirements for dress and behavior and a reluctance to name aloud the troubles that might mark a life, it was clear that I wasn’t going to live within ordinary standards, that I wanted to say things I wasn’t supposed to say, that I found the limitations unbearable. These poets taught me that I could be what I am, an untamable person, a person who writes.

Robin Coste Lewis, To the Realization of Perfect Helplessness

The second collection from the award-winning poet is one that breaks open poetic form in an activating and powerful way through images from her family’s archive and spare text. When reading the book, I felt awe not only at the work itself but how it allowed in readers like me—especially as a white reader—into the intimacy of Black spaces, family, and experiences without writing for me. I found this act of radically generous art making deeply moving.

I’m fighting the impulse to just copy and paste this entire interview, but here are words from Lewis at the Academy of American Poets on her use of text with photographs in this collection: traditionally, whenever there is an image on a page, if text is included, it has often been used as a caption, which illustrates or explains the image… And so, were I to have written, “In this photograph, my grandmother stands on the porch of her childhood home, where she was born in New Orleans in 1908,” viewers could have easily projected their own ideas onto the image and words about my grandmother, as if they could ever understand what those words mean historically—as if we could ever understand what it meant to walk in her shoes. People assume she spoke English, for example, because, of course that’s what being ‘African American’ means now.

But if any diaspora contains multitudes, it’s the African Diaspora. We assume so many ridiculous, boring, limited things about each other. It’s tragic. Add to these ideas the fact that once you say “poet,” “poetry,” “grandmother” or “grandmother’s photographs,” the whole world lapses into sentimentalism and the domestic, assuming what follows is a biographical narrative about a little old lady and her needles. In other words, patriarchy. Women have to fight every hour to be taken seriously, rigorously. Whereas, I’d venture to say that to be a Black woman born in 1908 and to survive requires a kind of tenacity and ingenuity most human beings know nothing about.