At night the house holds us like the thin shell around a yolk. We slide out of our shoes at the door. A small, dark enclosure crowded with sweaters and rain boots smelling of roses and mothballs leads to the kitchen, and we stop to notsee, notlisten, notthink about what is or is not in the house with us. Our persistent fear of intrusion butting against the persistent nothing that’s there, and our persistent feeling that it will always be nothing, that the loneliness will deafen us to joy, should such a feeling still be possible.We walk through the long, open rooms, past kitchen and dining room and finally in the soft cushion of afghans and eyeless stuffed animals no longer seen, we bend to run fingers through the thick weave of carpet. Plastic fibers catch our nails as we lower ourself onto its bed. We think Fur and Counting sheep, and of his woman’s forearm in an X-ray, tied at the wrist to the table so that when they order her favorite meal she can never quite reach. Can never taste it.

Our grandfather would say Patience is a virtue. He would say Good things come to those who wait.

Now, now, our grandmother would say, a mask of comfort over a plea to be quiet, to need nothing, to be more convenient. Now.

And we fall asleep, our hair weaving itself into the fibers that hold us in place.

*

When he sees us filling bags with rice and beans and grains we will forget in cupboards, dried and organized in jars more satisfying to observe than to open, he approaches, switching a gallon of milk to his left hand. He extends his right and says Hello, with a smile like he can’t believe his luck, his name is David.

Our grandfather would say Patience is a virtue. He would say Good things come to those who wait.

We do not reach out, and he wipes sweat from the jug on the lap of his dress pants.We wonder what day it is, if he’s coming from work. The sun is up, but at this time of year the sun is always up, it seems, and we don’t pretend to know how people pass the time.

I’m sorry I didn’t introduce myself the other night, he reaches out again.

We take the hand because we haven’t been trained to see an alternative. It is cool and moist and soft. It is confusing to be so close to a stranger. To anyone. To hold him. For a moment we think: This is what touch feels like.

We let go. You seemed busy, we say by way of an excuse. We cannot muster even a polite smile but remember the paid tab and add Thank you. For the drinks, I mean. A concession we know to make, but we do not wonder where such a lesson comes from.

Oh, David says, waving as if he’d made himself forget.

As if he is as embarrassed of our impotence as we are.

It is quiet. Our fingers undulate on the bottom of the thin plastic bag so the desiccated bodies of seeds surround our hand in a loose dance held back by the frailest barrier of plastic. We forget to try to make it easy; we forget that it is uncomfortable to stand with a stranger.With us.We wonder for a moment who will eat what we buy with money we shouldn’t spend as we imagine the satisfying pull of a razor across our skin.

We drop the bag into the red basket on our arm. It was nice to meet you, David, we’ve learned to say, and Be well.

His milk sweats onto his gray pants as he mumbles something, but we are already turning into the next aisle of cardboard boxes with cellophane windows, food looking out hungrily. Now, we whisper into their faces. Now, now.

We stand in front of a cooler, the low refresh rate of the bulb blinding. A child is singing ninety-nine bottles of beer, and when we reach for one, he sings ninety-eight. The mother smiles apologetically without knowing who her embarrassment is for.

Behind us, David says, That’s a good one. We turn.

He nods to the bottle in our hand. Sorry, he smiles, and we think charm is something he practices in front of a mirror. That, he starts again, didn’t go as I’d intended. I don’t mean to be forward, but I’d like—he grows shy and, maybe in a hiccup of professionalism, extends his card—I was wondering if you’d like to get a drink sometime. The gesture is so cumbersome and unattractive that we recognize ourself in it, and there is the same unidentifiable current of sympathy, a nothing that pulls between us like a rope: We never expect him to die. How do the privileged suffer? Where do they learn sadness? How does such a person die?

Our cold distance has lost its bite or its meaning, and so we capitulate. Moving from one nothing to another is made easy by the appearance of this man.

We consider his persistence and our day and the days before this one, alone in the house, and maybe in a dare with some part of ourself we thought dead or simply without thinking or from too much day/night alone in the yellowed house, we move out of the way of the cooler and gesture to the many bottles with our own. It is a gauntlet thrown, and we do not believe he will pick it up.We are unsure if it is him or us that we are testing, and for a moment we are filled with the power we associate with sin. The incredible strength of controlling our own fall.

The light makes him look pale and glistens off the short graying hairs on the hard edge of his wide jaw. The hand, the card, hovers between us like a lost animal, and his look is one of notunderstanding. Oh, I meant anytime. I didn’t mean tonight. I mean—he calculates and grasps—unless you’re not busy? He watches the thick paper of the card as he flips it between his fingers and into the dark of his pocket.

__________________________________

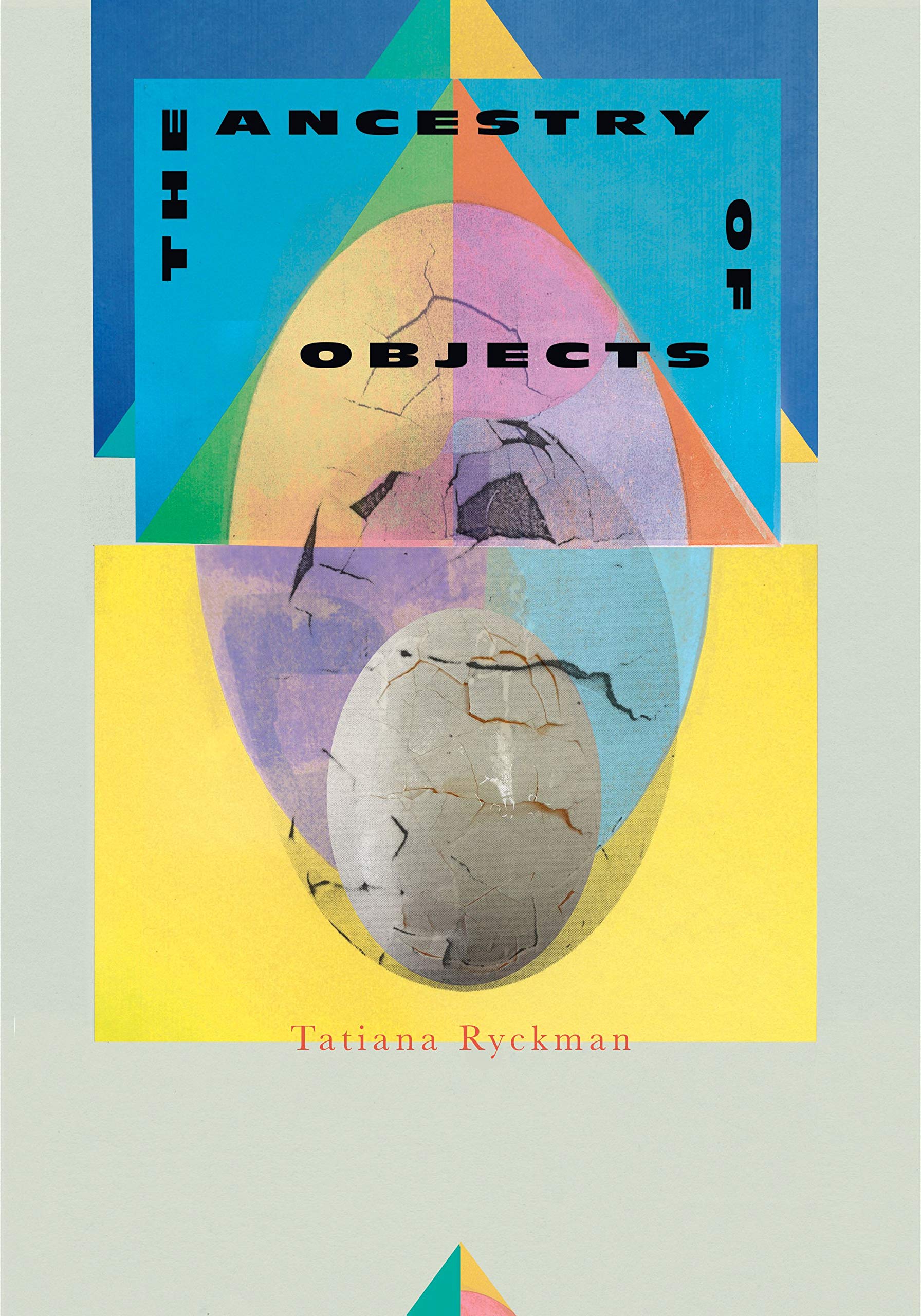

Excerpted from The Ancestry of Objects by Tatiana Ryckman. Copyright © 2020. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Deep Vellum Publishing.