The 1990s: A Surreal (and Sociopathic?) Era in America

Candice Wuehle on Books That Remember (and Resist) a Weird Moment in This Country

There were television sets on every floor of the house I grew up in, so when I think of the 90s, the first image that occurs to me is the image of other images. My family kept the TV on all day long, so The X Files or the O.J. Simpson trial or MTV’s House of Style or the Clinton impeachment or Cribs wove into a surreal narrative that braided catastrophe and assentation as equal threads.

Like a lot of teen girls, I spent half my time concerned with Y2K and Nostradamus and partying like it was 1999, and the other half studying my parent’s South Beach Diet booklet and Claudia Schiffer’s Perfectly Fit VHS. Civilization was moving toward end times and I was scared about that, but I still spent most of my energy counting calories and budgeting my allowance so I’d have enough for the tanning salon.

As an adult, I realize these seemingly oppositional interests actually stemmed from an overall obsession with vanishing. Of course, this was the primary theme that united the disparate images pumped out of the television and into my suburban home. Missing girls and women, alien abductions, weight loss ads featuring people standing in the negative space of their old clothes. I remember learning two facts when I was 16: fashion designers loved Kate Moss because her body made clothes look like they were still on the hanger, and Y2K would erase time as we knew it.

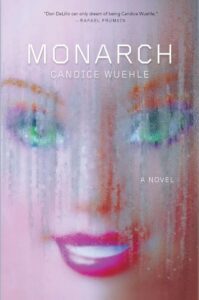

My first novel, Monarch, reckons with what it means to come of age during an era saturated in decay, absence, and doom. How do you stay in your own body when there are so many forces—commercial and actual—attempting to remove you from it? How do you know what’s true—or if anything is—in a decade that litigates reality from Court TV? And how do you know who you actual are—what you really want—in a world that attempts to scoop out your desires and program them into profits?

Being a teenager in America in the 90s who held on to her own ideas was itself a radical act. Here are five books that remember the era and offer up their own resistance to its commercial and patriarchal values.

Ariel Gore, We Were Witches

Christened “Ariel” by a mother who claims she wanted her daughter to “pass for a man on paper,” Ariel Gore is nevertheless certain she is actually named after Plath’s masterpiece. This titular tension mirrors the larger struggle of living as a single mother (who also happens to be a writer) in a society overwhelmingly dominated by the first Bush administration’s patriarchal control of single mothers’ economic and reproductive rights. We Were Witches enters “the soft, feathery war between art and motherhood” armed with the writings of Audre Lorde, Gloria Anzaldúa, and Kathy Acker—as well as a little magic. From “spells to prevail in family court” to an occult ritual initiated by an angelic Adrienne Rich herself, We Were Witches is both a sharp feminist critique of the early 90s and a delightful, bewitching celebration of art, women, and community.

Bret Easton Ellis, Glamorama

One of the few novels on this list both set and written in the 90s, Bret Easton Ellis’ Glamorama embodies and eviscerates the maximalist narcissism of the era. Conceived of as the kind of conspiracy thriller purchased primarily by dads at airport kiosks, Ellis twists his story of models turned terrorists by telling it through the voice of superficial “it” boy Victor Ward. With entire paragraphs devoted to the naming of celebrities, designers, and products that indelibly imprinted on the 90s, Ellis creates a near clairvoyant capsule of the time. The excruciating detail of Glamorama generates a sense of depthlessness; a plot of nouns, of surface, of missing identity. With bland flair, Ellis depicts America in its most sociopathic period.

JoAnna Novak, I Must Have You

JoAnna Novak’s highly stylized prose is as aesthetically obsessed as the dELia*s catalogues her characters flip through. Set over the course of several days in January 99, I Must Have You alternates perspectives between teen Elliot (a self-appointed “eating disorder coach”); her former client and best friend, Lisa; and her poetry professor mother, Anna. As a blizzard overtakes Chicago, all three women contend with their own fixations. While Elliot obsesses over her heroin-chic body, her mother goes on a heroin binge. Lisa, meanwhile, has sublimated her own obsession with weight loss on to her older boyfriend. I Must Have You recalls the 90s ethos of perfectionism at any cost—think Michael Jordan’s “flu game,” extreme diet culture, and celebrity suicides—in a scorching lyric screed.

Jenny Hval, Girls Against God

“It’s 1992 and I’m the Gloomiest Child Queen.” So begins Jenny Hval’s novel-manifesto-spell-screenplay, Girls Against God. Enraged by the racism and homophobia of her ultra-religious hometown, a teenager seeks haven in the Oslo’s nascent black metal scene. At the Munch Museum, Hval’s unnamed narrator is struck by the notion that all “naked young women in paintings are actually sitting there, hating.” With the help of her coven/band, Hval sets out to “rewrite the girl in [Munch’s] painting, save her, save us” through occultism and art. Queer and feminist theories are both forms of magic in Girls Against God, as are the mysterious depths of the early internet. “I type into the search bar the internet as a spiritual force. I delete it and instead type How the spiritual world is like the internet. I delete this too and write Find God on the internet,” writes Hval. “I don’t press Search, but I am searching… Dear God, who art online.” Hval captures the world-widening of the world wide web in this subversive and spectacular book.

Ottessa Moshfegh, My Year of Rest and Relaxation

Although the majority of Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation takes place in 2000, I think of this as a novel that is in many ways reckoning with the hangover of the 90s. Moshfegh’s nameless narrator has achieved every goal touted in a decade marked by Clinton Era prosperity—she’s “off duty model” beautiful, inheritance rich, Columbia educated, and art gallery job cool. She’s also desperate to numb out on sleeping pills and an endless loop of Ted Danson VHS tapes in an attempt to “reset” herself. While some have considered this novel a satire on pre-9/11 white wealth and privilege, I think of My Year of Rest and Relaxation as a Künstlerroman about a woman who has lived beyond meaning as it was defined by the decade in which she came of age.

___________________________

Candice Wuehle’s Monarch is available now from Soft Skull.

Candice Wuehle

Candice Wuehle is the author of the poetry collections Fidelitoria: Fixed or Fluxed, BOUND, and Death Industrial Complex, shortlisted for the Believer Book Award. A graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, she holds a PhD in literary studies and creative writing from the University of Kansas.