“That’s Just Playground Ball.” On Racism and Basketball in the 1970s

Theresa Runstedtler on the Proliferation of Black Players in Professional Basketball

“Basketball is merely the most natural channel of a black tide that has been flooding professional sports,” remarked journalist Terry Bledsoe. There were murmurs that this “Black tide” could be bad for business. By 1972, Black players made up around 60 percent of professional basketball’s workforce (up from 55 percent in 1970), and both leagues’ players associations had outspoken Black presidents. Could the leagues survive what appeared to be a mounting mismatch between the athletes and the fans?

African American ballplayers seemed to be making all the money and having all the fun, at the very same moment that white working stiffs were losing financial ground and spending their days doing increasingly monotonous jobs. Although 1972 marked the apex of earnings for white male workers in the United States, from 1973 on their real earnings began to stagnate and then continued to fall over the course of the next two decades. It was a sharp turn away from the prosperity to which they had grown accustomed.

Since 1960, their incomes had risen an astounding 42 percent. But the ensuing oil shocks and inflation, coupled with deindustrialization, globalization, plant closings, and the dismantling of unions, had ushered in a time of austerity and uncertainty. With diminished salaries and job security, some white workers found the tedium of the assembly line more and more unbearable. They had been willing to trade monotony for stability, but now corporations were refusing to hold up their end of the bargain.

Making matters worse, this economic downturn occurred just as Black Americans were ramping up their demands for more access to jobs and trades formerly reserved for white workers. But despite white complaints to the contrary, when urban labor markets collapsed in the early 1970s, it was Black workers who bore the brunt of the crisis. New manufacturing jobs that opened up were generally located in the suburbs. Housing policies continued to encourage white flight. As jobs and the tax base left, many African Americans found themselves trapped in decaying city neighborhoods and increasingly blamed for their own misfortune.

Some white hoops fans were part of the continuing out-migration to the suburbs, but most basketball arenas were still located in the downtown core. Even these more affluent fans expressed their annoyance at the expense and trouble involved in going to watch a bunch of Black men play ball. “It costs me a bundle of dough to attend a sporting event in the city. Babysitter, drive in, dinner for four, parking, tickets,” one white Philadelphian told author James Michener for his tome titled Sports in America. “I don’t intend to lay out that dough to be insulted by some black agitator or get mugged on the way home.” Black basketball came to represent the so-called urban crisis in more ways than one.

Given African American professional ballplayers’ growing celebrity, wealth, and power, it is hardly surprising that they became objects of intense public scrutiny amid the decade’s economic and urban decline. Worth a reputed $1.6 million over four years, Jabbar’s 1972 contract was one of the richest in the history of US sports.

By 1973, just as the recession really hit, sixteen out of the twenty-three NBA players with million-dollar, multiyear contracts were Black, and fifty out of the sixty-seven making more than $100,000 per year were Black. Reports set the average NBA salary at around $90,000 and the ABA’s average at about $37,000, when the median family income in the United States was just $12,050.

For Earl Monroe, playground ball was an inherited style born of the collective Black struggle, of making a creative way out of no way.

Even so, it was not just about the money or the fact that they “played” for a living. It was the way they played that rubbed some white fans wrong. With Afros waving in the breeze, players such as Earl “the Pearl” Monroe (NBA) and Julius “Dr. J” Erving (ABA) were remaking the professional game by infusing it with the aesthetics and ethics of Black streetball. Nurtured on the playground courts of Black neighborhoods, this aggressive, aerial, and fast-paced brand of basketball emphasized feats of individual athleticism, creative deception, and stylish improvisation, from trash talking and in-your-face shot blocking, to behind-the-back or no-look passes, to nimble jump shots and sometimes backboard-shattering slam dunks.

It was hard to deny that this influx of Black players brought something new to professional basketball. Exciting to watch, they were at once objects of white fascination and resentment, as playground ball and the Black city attitude that went along with it became popular targets of white disdain. Deemed “selfish,” unnecessarily flamboyant, and hostile to the “fundamentals” of the game, playground ball was initially a racial smear rather than a celebrated style.

In February 1972, Black Sports spoke with Monroe about his artistic influence on the professional game. As he sat in front of the microphone sporting a four-inch Afro, metal-framed aviator glasses, a large gold chain, and tight sweater, Earl the Pearl looked smooth. The interview offered a rare glimpse into the mind of the New York Knicks’ six-foot-three guard. Monroe was relatively quiet off the court. He did most of his “talking” through his playing. But he was by no means a pushover.

The year before, he had stood his ground against the Baltimore Bullets, refusing to play until team owner Abe Pollin acquiesced to his demand for a trade, dealing him to the Knicks. There was already bad blood between Monroe and the Bullets’ front office. The night before the 1967 draft, they had pushed him into signing a two-year contract for $20,000 per year, without the benefit of proper representation, and when it came time to negotiate a new deal in 1971, they tried to shortchange him. No wonder he was an opponent of the ABA-NBA merger. Without the threat of competition from the ABA, he might have been stuck playing for the Bullets for much less than his worth.

Earl the Pearl’s contributions to the game far outweighed his initial earnings. Placing Monroe next to the likes of former greats Bill Russell and Elgin Baylor, Black Sports asked, “How do you feel when you realize that you’ve changed the style of playing basketball?” However, Monroe was reluctant to claim such a central role in spurring this shift: “I think my style of play is basically just the style of about every Black player in America today. As you know, most Black players are, more or less, playground players and this is just about the basic style that I play.”

“If you come from a white middle-class environment, for instance, quite naturally you’re going to have the type of coaching and facilities to teach how to play basketball on a certain level.”

Although for many white sportswriters, playground play suggested a lack of sophistication or even a kind of Black moral failing, Monroe saw its development at the intersection of persistent racial and class discrimination in the United States. “If you come from a white middle-class environment, for instance, quite naturally you’re going to have the type of coaching and facilities to teach how to play basketball on a certain level,” he explained.

“But being in a Black ghetto area, you have to use the facilities available. And, of course, this changes the style because here you’re playing on places with cracks in the cement, you’re playing on half-moon backboards, basket rims that are bent and what not. So you kind of deviate the style of play and you kind of compensate for the different things.” For Monroe, playground ball was an inherited style born of the collective Black struggle, of making a creative way out of no way: “Before me, it was someone else. It’s just that I’ve had the exposure; people have gotten to see the way that I play.” Still, thanks in part to Monroe, this approach to the game had leaped from African American playgrounds to the professional leagues. His own life story, in many respects, resembled the conditions of urban deprivation that he described to Black Sports.

Born on November 21, 1944, Monroe had grown up in a rough part of South Philadelphia, learning the hoop game on the Black playground court at 30th and Oakford. Sometimes he and his friends went to the court at 30th and Tasker, where the white boys played, hoping to pick up a game. “If we black guys won,” he reminisced, “we’d have to fight our way out of there going home.”

Thanks to his inventive moves, he became a playground legend and a star player at John Bartram High School. He found his way out of South Philly through a scholarship at the small Black college of Winston-Salem State in North Carolina, where he played ball under the mentorship of famed coach Clarence “Big House” Gaines. Alternately known as “Slick,” “Black Magic,” “Einstein,” and “Black Jesus” because of his inspired play, as a senior Monroe picked up the nickname “Earl the Pearl” after local Black sportswriter Luix Overbea described his high-scoring games as “Earl’s pearls.” Monroe also helped lead the Rams to an NCAA Division II basketball championship in 1967, the first time a Black college had ever won an NCAA basketball title. The Baltimore Bullets then drafted him second overall.

Monroe’s transition to pro ball was far from seamless. The Bullets’ head coach, Gene Shue, a Baltimore native and former NBA player, helped teach him the ropes. Sensing that Monroe’s creative style would help put fans in the stands at the Civic Center, Shue gave the rookie a lot of space to play, reining him in only when necessary. His behind-the-back and no-look passes initially caught his white teammates off guard, creating turnovers. “They were missing passes even when they were wide open because they were used to traditional passes from their teammates,” Monroe recounted, “not these razzle-dazzle dishes that were coming from me.” Coach Shue asked him to tone things down a bit until they got used to his style of play.

Meanwhile, the referees kept calling Monroe for palming the ball when he made his signature spin move. As Knicks guard Bill Bradley described it, “He drove toward the defensive man only to turn his back on him at the last possible second before collision, pivot with his left foot, and head away at a forty-five-degree angle.” What made Monroe’s spin move unique was his “one-handed control; it was as if the ball were attached by a short string to his fingers.” Shue ended up having to pull the refs aside and give them films of Monroe so that they could see that he was not palming the ball. The way that he moved seemed to defy the laws of nature.

After Monroe scored an incredible 56 points against the Los Angeles Lakers in February 1968, a Baltimore sportswriter had started using the nickname “Earl the Pearl” in his columns. “It quickly spread to the national media and stuck in a way that ‘Black Magic’ and ‘Black Jesus’ hadn’t, except in the Black community,” Monroe recollected. It probably helped that “Earl the Pearl” was race neutral and appealed to a broader fan base. As Monroe’s confidence grew, he became even bolder on the court: “I started to make the crowds go wild.” He became a significant drawing card, attracting fans to the Civic Center and other NBA arenas across the country.

Monroe’s inspired play won him the NBA’s Rookie of the Year award in 1968. For him, it was not just an individual triumph. The award affirmed “a black approach to the way basketball should be played: with a whole lot of music up in the moves, a lot of rhythm like James Brown’s music or Mile Davis’s approach to jazz.” Trickery, improvisation, innovation, and mastery were central to his style of play. Black sportswriter Clayton Riley perhaps delineated it best: “Monroe’s attack, as an offensive ballplayer, was really the sports version of the sound that bop era musicians in America had certified as the brilliant message of gifted men, a song based on themes of personal expression emerging from a structured, collective effort.”

______________________________

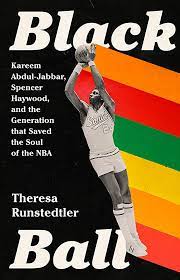

This article has been excerpted from Black Ball: Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Spencer Haywood, and the Generation that Saved the Soul of the NBA by Theresa Runstedtler. Copyright © 2023. Available from Bold Type Books an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Theresa Runstedtler

Theresa Runstedtler is a scholar of African American history whose research examines Black popular culture, with a particular focus on the intersection of race, masculinity, labor, and sport. She is the author of Jack Johnson, Rebel Sojourner: Boxing in the Shadow of the Global Color Line (UC Press, 2012), a book that explores the first African American world heavyweight champion’s legacy as a Black sporting hero and international anticolonial icon. Her book won the 2013 Phillis Wheatley Book Prize from the Northeast Black Studies Association. Dr. Runstedtler has also published scholarly work in the Radical History Review, the Journal of World History, American Studies, the Journal of American Ethnic History, the Journal of Sport and Social Issues, and the Journal of Women’s History, and book chapters in Escape from New York: The New Negro Renaissance Beyond Harlem, and In the Game: Race, Identity, and Sports in the Twentieth Century. She is a professor at American University and lives in Baltimore with her husband and son.