Ten LGBTQ+ Authors on the Books That Taught Them

James Frankie Thomas, Amelia Possanza, Richard Mirabella, Gina Chung, and Many More Reflect on Their Formative Texts

We all know the feeling of reading a book that touches us at our core. A book that somehow knows us intimately and takes us on a journey to understand ourselves more deeply. Especially for queer people, books can not only show us what’s possible, but they can also lead to revelations.

I asked ten queer writers who are publishing their first books in 2023 to highlight a book that enhanced their understanding of their queerness, writing craft, or both. It’s emotional to hear writers on the brink of having (or who recently had) their own books read for the first time talk about the words that shaped them.

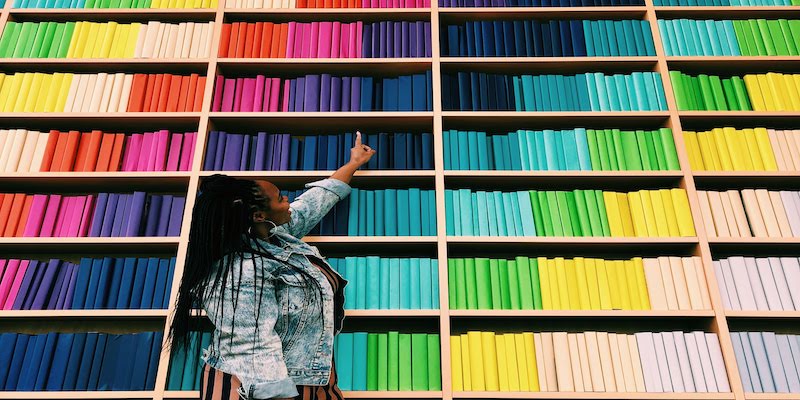

From novels to collections of essays, from classics to books published just a few years ago, these are recommendations you’ll want to add to your shelves—alongside the stunning work of these debut LGBTQ+ authors.

*

James Frankie Thomas, Idlewild:

The first time I read Nevada by Imogen Binnie, it was an Iowa City Public Library copy whose margins were annotated in pencil by someone with tiny handwriting and big feelings. Omg. This is too real I can’t take it. This book sucks it’s too much like my life. AAA! It me. Imogen Binnie’s 2013 novel has this effect on readers.

Nevada taught me how to meet my characters where they are, even if they’re literally and figuratively in the middle of nowhere, experiencing their gender as a sad shameful sex fantasy. It taught me how to let my characters be smart—as smart as me, even—while also letting them be wrong (about, for example, their gender being a sad shameful sex fantasy). It taught me that a character can be trans even if they don’t transition in the story.

It taught me that you can be trans even if you haven’t transitioned in your story—but also, let’s be real, you’re going to. Why else are you reading Nevada?

Lamya H., Hijab Butch Blues:

Audre Lorde’s Sister Outsider changed how I think about so many things: queerness, writing nonfiction, and, most importantly, the importance of words. Reading this beautiful, lyrical book, I learned to think of queerness as inherently connected to race, gender and class, of queerness as expansive and powerful. I learned that it was possible to write about oneself and tell deeply personal stories, while drawing on universal themes and making explicitly political statements.

And finally, I learned about the importance of speaking up: “My silences had not protected me. Your silence will not protect you” are lines that I’m haunted by to this day. I aspire to embody all these things that I learned from Sister Outsider in my own writing.

Richard Mirabella, Brother & Sister Enter the Forest:

No work of queer art has changed me, reorganized my thinking, and inspired me to push myself quite like Narrow Rooms by James Purdy—a brutal little novel about three men locked in a strange, passionate, and ultimately violent conflict. What inspires me most about this book is its resistance to portraying a recognizable gay life, or any life. It’s not “representation.”

The queerness of this novel lies in its rejection of a particular variety of acceptable American realism. This is the queerest of the queer, an uneasy and surreal rural fairy tale. I hope to, but will never reach, these transgressive heights. Narrow Rooms taught me to at least try to push my work somewhere I couldn’t possibly plan, to be open to the frightening surprises inside the work and myself.

Maggie Millner, Couplets: A Love Story:

I’ll never forget encountering the distinct queerness of Jane Bowles’ Two Serious Ladies sometime in my doleful early twenties, somewhere near the Pacific Ocean. The book follows two friends—Christina Goering and Frieda Copperfield—both of whom, in different ways, I immediately identified with: like Christina, I had always felt like an intense misfit; like Frieda, I was in a settled straight relationship, yet plagued by the strange feeling that my real life had yet to begin.

And it wasn’t just the characters that got my attention. Bowles’ prose was prickly and eccentric, full of non sequiturs and wisecracks and unsettling dialogue. I’d never read anything quite like it. I can’t remember how exactly I discovered the book: maybe I’d read somewhere that it was a favorite of John Ashbery or John Waters, or maybe I’d seen the chic new Ecco edition in a bookstore in 2014.

But I remember clearly what Frieda says to Christina after leaving her husband, on vacation, for a young femme sex worker named Pacifica: “I have gone to pieces, which is a thing I’ve wanted to do for years. I know I am as guilty as I can be, but I have my happiness, which I guard like a wolf, and I have authority now and a certain amount of daring, which, if you remember correctly, I never had before.”

Jen St. Jude, If Tomorrow Doesn’t Come:

We Deserve Monuments by Jas Hammonds is a book I’ve read countless times, and each time I find more reasons to love it. More recently, though, I was struggling to love my own writing and listening to the audiobook for the first time. It really illuminated my number one favorite thing about the story: the characters. Their chemistry leaps off the page, and though they aren’t always in agreement and don’t always want the same things, you see why they need each other.

What’s more, you feel why they want each other in their lives. I realized that’s what I want to capture most in my own work: the ways I love, notice, and treasure people, especially my queer found-family. Hammonds is a master of family, and a master of so many kinds of love.

Marisa (Mac) Crane, I Keep My Exoskeletons to Myself:

Through We the Animals, author Justin Torres taught me that queerness is a sensibility. His young child narrator doesn’t overtly say that he’s queer—obviously, he doesn’t have that understanding of himself yet—not until the very end when he is older, but we get a feeling of otherness, of queerness that lives in the very fabric of the book and this narrator’s life and world. Not only has it helped me understand the ways in which my queerness guides every detail, even the minutiae, of my life, but also how it can be present in unique and interesting ways in a character’s life, in a story.

Queerness doesn’t have to be stated for a book to be overtly queer, but it does need to possess a queer sensibility. In We the Animals, we witness a splintering, a transition from “we,” the three boys, to an “I,” a separation. But long before we learn that the narrator is gay, we see the world through the lens of his otherness, through his feelings of alienation but also of love and a desire for belonging.

We also get a queerness in the rhythm, the brutal and tender poetry of the book—there is an early scene where the boys dance with their father in the kitchen. The rhythm of the book is like dancing, even if you aren’t yet sure what you’re dancing for or who you’re dancing with.

Jennifer Savran Kelly, Endpapers:

One of my most beloved books is Edinburgh by Alexander Chee. I read Chee’s gorgeous novel about six years ago, as I was drafting my queer debut and having a lot of feelings about the potential of coming out so publicly. In breezy, lyric prose, Chee writes openly about young queer self-discovery in the midst of childhood sexual abuse. The tale he weaves is at once heartbreaking and stunning, exploring the added difficulty of trying to understand one’s own sexuality while experiencing the trauma of sexual violation.

Sadly, it’s a trauma that I and too many others relate to, and one that’s certainly complicated my own ability to understand and find comfort around my sexuality and gender identity. In terms of the writing, Chee’s novel showed me how it could be possible to tell a story of queerness and trauma with beauty and hope. I didn’t want it to end.

Amelia Possanza, Lesbian Love Story:

Recently, I was asked to teach a queer writing workshop to a group of New York City public school students in the GSA. Our first day together, I asked them what they thought made a piece of writing queer. “Sexuality,” said the boldest among them. “But I’m not really sure because I’ve never read any queer writing.”

At that moment, I wished I could rewrite the entire syllabus around Lidia Yuknavitch’s The Chronology of Water, which had exploded everything I thought I knew about queer storytelling when I first read it nearly a decade ago. I had always identified as a water gay, but it wasn’t until I read her experimental memoir that I considered how that identity could shape not just the content of what I wrote but also its very form and shape—its chronology.

She employs what she calls “the chronology of water” to tell the story of her own early entrances into the pool, her time in Ken Kesey’s writing group, and her difficult experiences with abuse, addiction, and miscarriage, rarely reverting to the actual lived order of things to tell the story. “All the events of my life swim in and out between each other,” Yuknavitch says. “Without chronology. Like in dreams.”

Gina Chung, Sea Change:

I first read Zaina Arafat’s You Exist Too Much not long after its release in June 2020, in what felt like a fever dream. I sat down with the book one hot, lazy summer afternoon, and didn’t emerge from it until the sun had set and my back hurt from sitting in one position for too long. I felt a strange flush suffuse my body as I read about the heartbreaks and suffering of Arafat’s protagonist, a bisexual Palestinian American woman struggling with shame, love addiction, disordered eating, and a strained relationship with a mother who always seems to be holding her at arm’s length. (The title of the book comes from something her mother says to her after she comes out).

It’s considered a bit of a cliché nowadays to say that a book made you “feel seen,” but that’s the only way I can think of to describe the thrill of recognition that coursed through me as I continued reading and rereading breathlessly into the night. As a bisexual woman and the daughter of immigrants myself, I spent much of my teens and twenties like Arafat’s protagonist, falling in and out of obsessions with emotionally unavailable crush objects, while in denial about the nature of my sexual desires.

Realizing the truth of my queerness in my early 30s has been a vulnerable, thrilling, and sometimes shame-filled journey—I have felt, on various occasions, both “too much” and “not enough.” But Arafat’s powerful, moving novel reminds me that what is more important than trying to find some idealized perfect balance between these two arbitrary designations is celebrating the mere fact that I do exist, in all my queerness, and that that alone is enough.

Tembe Denton-Hurst, Homebodies:

I’d have to say The Color Purple by Alice Walker. It was one of the first instances that I saw queerness as a path to freedom, a radical kind of love that had the power to transform and heal. Shug being sure of herself and reflecting that back at Celie, seeing Celie, changed the way that Celie saw herself. And what is love if not a mirror?

It doesn’t end perfectly for them, but it showed me the way something can be messy, deep and complex, but also beautiful.