Most of us considered leaving art school after the first year. The education we were getting mostly consisted of identifying the limits of our creativity and the huge gaps in our self-understanding, and detailed insight about our professors’ bodies of work, which we were shown on projectors on the last day of class, always, like a treat, like they had been waiting the whole semester to reveal to us how amazing they were.

“Beautiful work,” a professor might say during critique. “Just really jarring.” Then the professor would stand in front of our work thoughtfully, turn around, and say, “What does everyone else think?” It was the kind of discourse that didn’t seem worth paying thousands of dollars for. But here we all were, paying for it. Here we were signing up for another semester of it. What else could we do? Go back to our hometowns and be ceramic teachers at local guilds? Get jobs at indie bookstores and do art in our free time, continuing to take advantage of the college’s free lectures and art shows and shuttle buses and even studio space if we were sneaky enough? It made suspiciously too much sense.

“I should move to New York,” Suz often said. “The art scene here is not what I expected. It’s like there’s no ambition.”

I never considered leaving school. I understood the education I was getting was of questionable quality and limited practicality, but I loved college life. I loved the deadlines and critiques and readings. I loved having access to the studios at any time in the night or day. I loved my apartment, a tiny, drafty second-floor studio I had all to myself, paid for by loans with interest levels I was not taught to understand. I left supplies out, sketchbooks open, and finished work pinned to the walls. I played music from my laptop in my tiny kitchen while I made quesadillas in the microwave with American cheese slices. I ate at a step stool on the floor next to the foot of my bed, a setup I referred to as the Formal Dining Room. Every morning I walked 1.5 miles to school carrying a huge portfolio, often in the rain, thinking, No one has ever been so lucky.

“What do you think of my film project idea?” Suz said. We were walking from where she parked her car to her apartment a few blocks over. “I don’t normally make work about my family. Does it sound cheesy?”

“I mean, everyone always loves your work. You have nothing to worry about.”

“I’m asking your opinion.”

“My opinion is that everyone always loves your work, including me. It’s going to be great.”

I could tell the compliment disappointed her. She was looking for something deeper from me, perhaps something rooted in art theory. A reference to some other artwork, or an awareness of the symbolism her idea might reflect. This was how she talked in class, relating our peers’ work to art movements of the past, seeing layers of meaning in smears of charcoal, going on and on about the texts we were assigned to read. My own artistic interpretations were shallow and simplistic by comparison. “That hand looks too small for that body,” is a critique I might offer. Or, “I’d like to see more red.”

“I’m going to cut the footage of my mom with other things, obviously. I want to work with the idea of my mom as a woman in a society that hates women, and with my own role in participating in misogyny.”

“Oh, wow,” I said.

I liked watching Suz’s brain work, even if I usually couldn’t follow its path. It was interesting to see how quickly she could get from Point A (a pen drawing of a house on fire, for example) to Point B (the fragility of humanity) without making any huge logical leaps. I always thought she must have already had the fragility of humanity on her mind and was looking everywhere for new ways to think about it. The idea of approaching art—or life—with your own agenda, rather than waiting to see what it told you, seemed original to me. And the idea of pondering the fragility of humanity in your spare time seemed hilarious.

We turned onto Suz’s street, which was lined with lush green trees. These kinds of tree-lined streets of historic buildings always gave me a jolt of realization that I was living in San Francisco, a place where millions of different kinds of people have lived, cared for, and built communities.

Small cities like Lodi, where I grew up, offered only sameness and emptiness. Green lawns, cars baking in the sun, hundreds of miles of sidewalk that rarely got used.

Not that San Francisco was a utopia or anything. There was garbage in the streets and human feces in doorways and it was pretty likely your bike would get stolen if you left it on a bike rack overnight without using two sixty-dollar U-locks. But people cared about the city, and it made the city feel alive. People put flowerpots on their stoops. People opened coffee shops and named them after the neighborhood they were in. Sometimes you’d see a fragile new tree planted on one of the sidewalks, and everyone, even the street drunks, would be careful not to run into it.

I took up space in this miraculous city. Thinking about it felt electric.

We put our things down inside her apartment and then went through the kitchen window to the roof. We sat on plastic chairs, took sweaters out of our bags and spread them out over our laps so we wouldn’t get cold or sunburned. You could never tell in San Francisco. We were quiet for a few minutes, a comfortable, relaxed silence I didn’t experience with many people, and then Suz pulled a book from her bag and started reading it. I took out my sketchbook and a candid photograph of myself on Christmas when I was eleven, sitting among unopened presents under a Christmas tree looking displeased, and started drawing my own chubby preadolescent face on a clean new sheet.

__________________________________

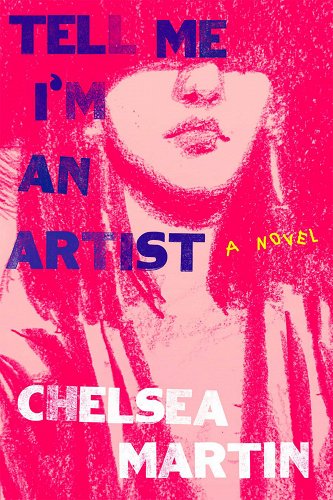

Excerpted from Tell Me I’m An Artist, copyright © 2022 by Chelsea Martin. Reprinted by permission of Soft Skull Press.