Taylor Byas on Writing About Her Hometown

In Conversation with Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan on Fiction/Non/Fiction

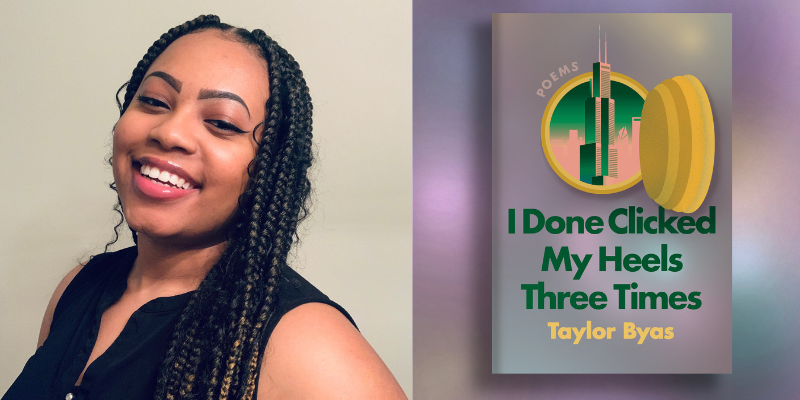

Poet Taylor Byas joins co-hosts Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan to discuss writing about Chicago, which she does in her Maya Angelou Book Award-winning collection of poetry, I Done Clicked My Heels Three Times. She talks about growing up in the country’s most segregated city, and considers its long traditions of Black, working-class, and ethnic literature, including writers like Nate Marshall, Lorraine Hansberry, Patricia Smith, and Jose Olivarez. She explains how moving away has given her a new perspective on Chicago’s politics, history, crime, and beauty. She reads a poem (“You from “Chiraq”?”) addressing how outsiders view the city, as well as from a crown of sonnets about the South Side.

Check out video excerpts from our interviews at Lit Hub’s Virtual Book Channel, Fiction/Non/Fiction’s YouTube Channel, and our website. This episode of the podcast was produced by Anne Kniggendorf.

*

From the episode:

Whitney Terrell: We’re glad to have you. The Maya Angelou Book Award is close to home since it’s sponsored by the Kansas City Public Library and six universities here in Missouri, where I live. We were thrilled that you were chosen by our finalist Judge Randall Mann and our readings committee. But you’re from Chicago, not Missouri, and you identify as a Chicago writer. Some of the most famous American writers that I’ve grown up reading are writers who write about Chicago. Richard Wright, Saul Bellow, Gwendolyn Brooks, Lorraine Hansberry, Upton Sinclair, Nelson Ahlgren, Stuart Dybek, Sandra Cisneros, just to name a few. Contemporary black poets like Nate Marshall, Eve Ewing, Patricia Smith, then of course, you. Given that list of names, it seems to me like Chicago writers have been among the most politically active and radical writers in the American literary tradition. I wonder if you think that’s true? And is there something about the city and its politics that makes writers from Chicago that way?

Taylor Byas: I think that is true, and I think there is something about the city that definitely contributes to that. Chicago is still—I believe—the most segregated metropolitan area in America. And so I know for me, there’s a very particular experience of being a person of color and growing up in a place that’s extremely segregated, which for me means growing up in a community of people that for the most part look like you and are going through the same things that you’re going through, and there is a particular comfort with that. Then I think over time, there’s the dissonance of safety and comfort from growing up in the community of your people. And then realizing what comes with that, which is ultimately, systemic and systematic structural racism, lack of resources, militarized police, those sorts of things. I think there’s this very interesting juxtaposition between the very early experience of being in a community of people like yourself, and then over time, realizing that this sort of segregation of the city comes with a lot more that is not as joyful and not as comforting as those earlier experiences.

There’s a shift that always happens, and maybe at different times for people. For me, in particular, I played volleyball when I was younger, and one of the things that I remember was traveling to other schools, particularly on the North Side of Chicago, and being struck by the differences between our schools and realizing how much more technologically advanced and how much more funding these sorts of schools had. So you have experiences like those where you realize the intense segregation of the city ultimately hurts you, maybe in ways that you don’t realize until you are forced to encounter those other parts of the city in particular ways.

On the other hand, Chicago just has a very rich history. You mentioned Eve L. Ewing, I’m thinking about 1919. We have Chicago being one of the cities where a lot of people settled in during the Great Migration. I think Chicago is just really ripe with a lot of complicated history, and coupled with the personal experience of growing up in your community and then realizing that it’s not as sweet as it seemed when you were younger. I think both of those things together are really conducive to a lot of political writing. For sure.

V.V. Ganeshananthan: That’s interesting because some of what you’re talking about suggests a particular kind of coming-of-age story. Of course, not all of the literature coming out of Chicago is that, but the transition that you’re describing suggests a very particular way that coming-of-age might play a role in literature for people from Chicago. Its geographic location has made it this place of great interchange—a place that people come to and spend key periods of their life. Some of the writers that we mentioned above weren’t necessarily born in Chicago, but maybe arrived there and spent formative periods of their lives there and then moved on. They also wrote in very specific ways—in a way that you do as well— about specific neighborhoods.

It seems to me like Chicago literature foregrounds are Black life, working class life, and particular ethnic communities. There’s all sorts of overlap between those categories, which are imperfect and intersectional. I’m thinking of Wright’s Native Son, Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun, which I remember reading in high school and being so blown away. Often, the only [contemporary] play a kid reads in school is A Raisin in the Sun, right? Like, Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, Sandra Cisneros’ The House on Mango Street. These are just a few examples of Black life, working class life, and the life of ethnic communities that exist across American literature. But Chicago’s contribution in all three of those categories is really distinctive. And I’m curious about why that literature has had such a great impact on us, and if I’m missing other ways we might think about those contributions. Am I missing any categories that we should be thinking about?

TB: I think there are a lot of categories that we should be thinking about. But I do want to focus on the Black, ethnic, working class literature that you’re talking about. What comes to mind—and I didn’t really think of Chicago in this way until I left and we can talk about that a little bit—I think in a lot of ways, a lot of what happens in Chicago, or a lot of the literature that I read about Chicago, can often serve as something symbolic or metaphorical about what happens on a larger scale in America, and oftentimes globally.

I think Chicago is very particular. Its politics are so particular, and again, its segregation is so particular that I think the narratives that come out of that offer this very magnified, but also very personal version of what happens on this much larger scale. And when we come to those texts, we often get these much larger lessons of history maybe along with these really personal narratives. I think about the impact of these works in schools, for example, or like, some of the school conversations that I had about A Raisin in the Sun.

A lot of what we talked about was this larger umbrella of the American Dream. This story about Chicago would then become something that stood in for this larger understanding of how people were trying to survive and make it in America. Going back to that experience of learning, over time, what it means to be in a very segregated place as a person of color, and then having to go outside of that community to then realize what that really means. I think that the coming-of-age narrative is very universal for a lot of people. I think Chicago politics allow for very particular narratives to be written about that, but I think it happens on different scales and in different ways everywhere. There’s something about the narrative that comes out of Chicago that a lot of people of color all over the world can really relate to.

Ultimately, I think there’s a universality in those narratives that I think serve really well when putting them in curriculum, or just having larger conversations about people of color’s experiences in America. For example, those narratives of when you first realize that you’re Black, or those narratives of when you first realize that racism exists when it happens to you? Those stories of Chicago really provide an easy space for us to talk about those sorts of narratives because of the environment, because of the segregation, because of its politics, and its corruption, etc, etc, etc. So I think that’s what happens and why those contributions from Chicago are so distinct.

WT: I was thinking, when you were talking about the siloed nature of life in the neighborhood that you grew up in, in Kansas City, is very racially segregated as well, which is something that I have written about. But it also doesn’t have, for instance, Polish American neighborhoods, which is what Stuart Dybek writes about. And I wonder if maybe that’s part of it. There are these very strong neighborhood borders, not just in between Blacks and whites, but between different ethnicities in the white community. Is that true of Chicago? Do those boundaries still hold?

TB: Yeah, in addition to those racial divides, there are also very intense class divides as well, so you also have those very distinct divisions. And then we also have neighborhoods that are heavily Hispanic, for example. So there’s a multitude of separations, not just the line between Black and white that we often think about.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Mikayla Vo.

*

Taylor Byas:

I Done Clicked My Heels Three Times • Bloodwarm • Poemhood: Our Black Revival: History, Folklore & the Black Experience: A Young Adult Poetry Anthology (Ed.)

Others:

Richard Wright • Saul Bellow • Gwendolyn Brooks • A Raisin in the Sun by Lorraine Hansberry • The Jungle by Upton Sinclair • Nelson Algren • Stuart Dybek • The House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros • Nate Marshall • 1919 — Eve L. Ewing • Patricia Smith • Promises of Gold by Jose Olivarez • Carl Sandburg • Chi-Raq (film, dir. Spike Lee) • Gordon Parks • Brandon Johnson

Fiction Non Fiction

Hosted by Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan, Fiction/Non/Fiction interprets current events through the lens of literature, and features conversations with writers of all stripes, from novelists and poets to journalists and essayists.