Taking an Author's Photo Is Like Going on a First Date

Nina Subin on the Careful Process of Taking a Writer's Headshot

It has been said that, to understand the process, every writer should have worked for a while as an editor and every editor should have written at least one book. The same is true for editorial photography. In my case, I worked for many years both as a photo editor (at New York, Esquire, and the New York Times) and as a photographer, mainly for travel magazines. For the last 20 years, I’ve left editing to do my own work: still-lifes for myself and commissioned portraits, generally of visual artists and writers.

Writers may be difficult in their private lives, but on the other side of the camera lens they tend to be nervous but sweet. At the point where they need to be photographed for a book jacket or a magazine article, the book they’ve been working on for years is finally done (and the reviews aren’t out yet). Unlike actors or “celebrities,” they are unaccustomed to being photographed. They have no physical “brand image” to project, or a “better side” for their profile. Almost all writers start the session by telling me that they are not photogenic. (I tell them to decide after they have seen the photos.)

I try to make the process relatively painless. When I’m shooting in my studio there’s no loud music or a hubbub of bustling assistants. I’ve usually read at least a few chapters of the forthcoming book—if I don’t already know the previous work—to get a sense of the person. We talk about the book or travels or families—anything except politics, which these days makes anyone look too depressed for a portrait.

It’s rather like a long first date. The writer starts out uncomfortable and tense. If hair and make-up have been requested, that may be a first experience. Initial movements and expressions tend to be awkward. But then the conversation rolls on, the logistics become familiar, and the writer usually drifts into a more relaxed state. This may well be boredom, but from my point of view, the face softens and that’s often when the best pictures are taken.

Almost all the work is done in my studio or in the writer’s own home or studio. Sometimes, when it’s appropriate for the book, we move outside, in natural or urban street locations. I especially enjoy photographing writers in their own environments, where they become part of what is almost a still-life of their life, surrounded by familiar objects. William Dalyrymple, at his home outside of Delhi, became distracted admiring his lovely cockatoo. Yoko Tawada felt like being photographed holding something red: she suggested a lobster but settled for a pomegranate, which I thought would be less Daliesque.

When this isn’t possible, the photos are taken in my studio, which is on a high floor in Chelsea with wonderful natural light. Rather than plug the subject into an existing set or a preconceived or standard “look,” I move flats and lights and reflectors and curtains around, and we try different angles or articles of clothing, so that there are always things about the individual that ultimately determine the portrait. From my years as a photo editor, I know that the best photographers not only do the assignment—what the client wants—but also explore the other unexpected possibilities that grew out of the shoot.

Writers are often surprised that it isn’t easy. It’s work. They can’t just stand or sit there and let the photographer do everything. It’s a collaborative process and they often leave exhausted. Many marvel at how models can do this every day. But usually, when they receive the photos that are sent for a final selection, they feel it was worth it in the end. And quite a few come back for a second date, years later, when their next book is done.

*

Click to expand.

- William Dalrymple

- Yoko Tawada

- Barbara Epler, New Directions Editor

- Tayari Jones

- Rivka Galchen

- Ta-Nehisi Coates

- Ayad Akhtar

- John Keene

- Josh Ferris

- Meg Wolitzer

- Reniqua Allen

- Pankaj Mishra

__________________________________

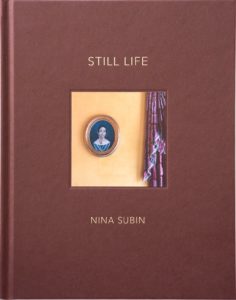

Still Life by Nina Subin is out now.

Nina Subin

Formerly the photo editor of the New York Times Sophisticated Traveler, Esquire, and New York magazine, since 2000 Nina Subin has devoted herself full-time to her own work: portraits from her base in New York City and photographs of sacred places and landscapes around the world. Her portraits of writers, visual and performing artists have appeared in numerous magazines, newspapers, book jackets, and publicity campaigns. She has done assignments for, among others, Little, Brown; Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; Harlequin; Farrar, Straus & Giroux; Riverhead Penguin Putnam; Random House; New Directions; Crown, Scribner, and Artisan Books; and Harper Collins, as well as many publishers abroad. Her photographs have appeared in The New York Times, Oprah, Bomb, Elle, German Vogue, People, Time, Artforum, and Time Out.