Tackling Ballet’s History of Anti-Blackness as a White Woman

Karen Valby: “It is not my job to be a white woman beyond reproach—some mythical anti-Karen that doesn’t even exist.”

I try not to let apology creep into my voice when someone asks me for my name. It’s only been a few years since Karen became a catch-all for meddling, abusive white women who take it upon themselves to jeopardize a Black person’s peace. In 2020, Amy Cooper immortalized the name after she harassed and called the police on a Black man, insisting that his binoculars and his love of birds posed a threat to her. The internet renamed Cooper the “Central Park Karen.” Since then, Karens have ruined barbecues, shut down kids’ sidewalk candy sales, and tried to criminalize people for going about their business. Karen is a danger. She is a drag. No wonder friends earnestly began wondering if I should start using my middle name.

By the time Karen became synonymous with menace, I was already the white adoptive mother of two Black daughters. Recently we had to move and a cute rental in our price range popped up on Karen Avenue. Not a chance, no matter how good the square footage. Being raised by a Karen is indignity enough; I couldn’t drag my daughters to her homeland. When I meet new parents in the waiting room of Ballet Afrique, the dance studio in Austin, TX, where both of my girls have taken classes since they could walk, I try not to lead with an easy joke about my name. I need to be at peace with the fact that my name is a threat spoken aloud.

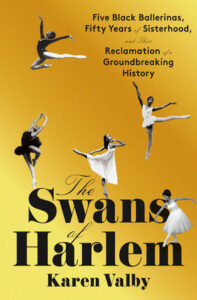

Just as I was not the first or necessarily best option to mother my darling girls, nor am I the obvious person to write about the intimate experiences of Black women who came of age during the Civil Rights Movement. My new book The Swans of Harlem: Five Black Ballerinas, Fifty Years of Sisterhood, and their Reclamation of a Groundbreaking History is about young women who gave their entirety of selves over to an artform that had long considered the Black body and temperament unsuited to the classical stage.

I think part of the reason the women trusted me with their memories was because of their investment in my daughters’ wellbeing. These women well understood the value of a Black dance institution, and how it can keep the soul of a young person healthy and whole. The Dance Theatre of Harlem was like a lighthouse to these women in the 1960s and 70s, when ballet companies typically wouldn’t even let a Black person audition.

My job—as both mother and writer—is not to negate, pollute, or dilute a Black woman’s experience.In the book, McKinney-Griffith described how she coped with so often being the only Black person in her years of training before becoming a founding company member of the Dance Theatre of Harlem in 1969. “When you live in this skin,” she told me, “You grow up knowing you have a special position in the world that you must protect. It’s something all Black women understand. I don’t think we’re even aware when we’re doing it, but we’re always protecting ourselves—in school, in different communities. You put on your armor and wear blinders and focus. You’re used to thinking two things at once: Yes, I’m the only Black person here and Yes, let’s do this.”

Conversations like that with Swans threw open windows for me. For over three years, I’ve had the luck of hearing the triumphant and tragic stories about their formative years together, when as young women they accomplished what a doubting, rigid world said couldn’t be done. The magic of their union didn’t just exist on stage, under sublime spotlight, set to the roar of standing ovations. These women’s sense of community is deeper than time or place. As girls, they had to lean on each other to survive and surpass expectations.

Fifty years later, they formed the 152nd Street Black Ballet Legacy Council to protect and celebrate the irrefutable fact of their existence as artists and women. Their highest power has always been in company with each other. By some miracle, they let me into their circle. And I tried not to squander their embrace by centering myself, which would have rightfully forced the women to put their guards up. Yes, I’m the only white person here and Yes, I take seriously the responsibility and honor of this.

It is not my job to be a white woman beyond reproach—some mythical anti-Karen that doesn’t even exist. My job—as both mother and writer—is not to negate, pollute, or dilute a Black woman’s experience. So, I choose to think of my name as an asset. It’s a reminder of the potential harm I can bring to Black spaces. Speaking it aloud enlivens the tender barrier that exists between me and Black friends and family. It keeps me careful, and accountable.

How easy we white people can tell ourselves that we’re an ally, that we’ve done the work, that we’re not a part of the problem, that we’re one of the good ones. But rarely have I seen that kind of defensive righteousness—assumed because of the way we vote, perhaps, or because we had a Black Lives Matter sign in our yard for a time—serve as a path to true connection. The infinitely kinder cousin of ignorance is curiosity. What if a Karen could practice putting down her manufactured grievance, and her claims of victimhood? Imagine if she tried listening for a change, even if that meant hearing uncomfortable truths about herself.

__________________________________

The Swans of Harlem: Five Black Ballerinas, Fifty Years of Sisterhood, and Their Reclamation of a Groundbreaking History by Karen Valby is available from Pantheon Books, an imprint of Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.