There were two buses—one to New York and one to Boston. I got on the New York bus and sat next to Jacquie Beller. She pointed out the window to someone’s older brother. “I just had S.E.C.,” she said. “With that boy. It was so great.”

S.E.C. was short for serious eye contact. It was one of our main goals all summer. He turned and caught us staring at him.

“I’m putting that on my list,” she said. “I don’t ever want to forget it.”

The worst thing about being on this bus was that Labor Day was in eight days and then school would start, which was unimaginable but that wasn’t going to ruin the two and a half hours that lay ahead of us. We had plans to take the love quiz in Seventeen, make lists of things that happened at camp, and pass around our address books to get everyone’s phone number. She had forced her mother to mail her the Weekly Wag, which was a New York City newspaper that had personal ads in the back, like if a man saw a woman at a concert or on a street corner, but was too shy to ask her out, or couldn’t because she was with another man at the time, but he was sure she was the love of his life, he could put an ad searching for her in the back of the Wag. We loved reading those.

One of the male counselors got on with a clipboard and read off everyone’s name who was supposed to be on the bus to New York.

“Jacqueline Beller?”

“Here.”

“Nedim Adem?”

“Here.” He was from Istanbul, Turkey, and someone was going to pick him up at the bus stop and bring him straight to JFK.

“Janie Rand?”

“Here.”

“Swanna Swain?”

“Here,” I said.

Then another counselor got on the bus and said something to him.

“Oh, Swanna, you have to get off the bus actually. Your parents are picking you up. Your mother called the office.”

“Not my mother,” I said, confused, and a few people laughed even though I hadn’t meant to be funny. I’m one of those people who always gets a laugh for absolutely no reason.

“Really, you have to get off the bus,” the counselor said.

My father had moved out before camp started, actually last Christmas, which was one of the reasons I got to go to camp in the first place, so I knew there was no way they were picking me up together, unless—I actually wasted my own time thinking—they weren’t going to go through with the divorce.

“I don’t think my parents would do that,” I said. “They’re separated.” Even though my voice accidentally caught on the word separated, a few more people laughed.

“Well, I guess it’s just your mother coming. But you have to get off the bus.”

“My mother doesn’t even know how to drive,” I said.

I hadn’t heard from her the whole time I was there although I’d written to her once a week at the address she’d given me

for the artist colony where she was spending the summer. The other reason I got to go to camp.

I started to panic a little. My father would be at the bus stop waiting for me in New York. I didn’t know what to do. I got up and walked to the front of the bus, intending to explain to the guy more privately that I would have to call my father first to check that I really was supposed to not come home.

When I got to the front of the bus, I saw my bags had been removed from the luggage compartment underneath and placed on the grass.

“I’m really sure I’m supposed to be on this bus,” I said.

He showed me the little piece of scrap paper with someone’s scrawled handwriting. Swanna Swain—mother will pick up!

“Mother? Or father?” I said.

“The bus has to go, Swanna.”

I tried to think if there was anything I especially needed in my duffel bags. My contact lens kit was in there, the saline solution, enzyme tablets, and the machine I needed to disinfect them. But maybe I could just leave them there and stay on the bus and drive off without them.

“This sucks,” I said. Again people laughed as if I had my own personal live studio audience. Something told me I should stay on the bus. Just sit back in my seat next to Jacquie and pretend I had narcolepsy or something. In two and a half hours I would be back in New York City. My father would be at the stop waiting for me.

We would have dinner someplace great. Shakespeare’s for a burger or McBell’s for a chicken pot pie. I liked McBell’s even though their salad dressing was a clear thick mucusy sauce with little red dots strangely suspended in it and their bread had raisins in it.

“I wouldn’t tell you to get off the bus if you weren’t supposed to get off,” the guy said.

“I’m going to stay on the bus because my mother doesn’t know that my dad made special plans to pick me up, and when she comes someone in the office can just tell her.”

“She is supposed to be on the bus,” Jacquie said. She was standing in the aisle.

“I’m sure your parents communicated with each other,” the man said.

“I’m sure they didn’t,” I said.

I started to head back to my seat but the man literally grabbed my arm. He actually blocked my way and sort of forced me off the bus like an SS officer in Nazi Germany, and the doors closed in front of me. I just stood there holding Jacquie’s copy of the Weekly Wag.

I watched the bus drive down the dirt road, past the infirmary and the tennis courts, until it was out of sight.

I went to the office cabin to call my father, but the door was locked. I went to the phone booth on the porch of the canteen and dialed my father’s number with a 0 in front of it. “Collect call from Swanna,” I told the operator.

But the phone rang and he didn’t pick up. “The party you are trying to reach is unavailable,” the operator said after I forced her to try three times. He was probably out buying some snacks for me to eat when I got home. I couldn’t wait to pop open a Tab.

I never saw a place empty out so fast. Over the next three hours, the counselors, music and dance teachers, the entire staff hot-tailed it out of there. It was sad, like when you see a clown smoking a cigarette before the circus. Seeing camp empty kind of ruined it. There was not a scrap of food left on the entire campus.

There had been one car in the parking lot, but when I came back from trying my father again, I was startled to see it gone.

I sat on the grassy hill with a scowl on my face.

I took off my high heels and laid them on the grass next to me. The leather on the heels was worn down. I’d worn them every day the whole time I was there. I took my diary out of one of my duffel bags and tried to write but the sentences came out too short and fast like trying to talk between sobs.

I looked at the Weekly Wag. Jacquie and I had called one of the ads in the back. It was visiting day and her parents took us both to dinner at the Red Lion Inn in Stockbridge, Mass. They had a room there because they were making a weekend out of it, and while they were at the bar we went up to the room and called the number in the ad from the hotel phone. A man answered. “Hi,” I said, “I’m calling about the ad you placed in the Wag. I think I might be the woman you’re looking for.”

“You’re kidding,” he said, sounding incredibly hopeful.

“Well I was in row C, seat 11, and I was wearing a brown suede jacket and I have long blond hair and aviator glasses and I was with someone,” I said, reading the details he had put in the ad. “But I did definitely notice you.”

“I can’t believe it,” he said.

Jacquie had her face plastered next to mine, trying to hear him.

We talked for a while about how great the concert was, and then I could tell Jacquie was starting to get nervous that the phone bill would be too big. And then I blew it. I pronounced John Prine like Preen, and the man said, “What?”

And I said it again, “I just love John Preen.”

And the man said, “I think it’s Prine. I’ve never heard anyone pronounce his name like Preen.” And then I hung up and Jacquie and I laughed hysterically for about an hour.

__________________________________

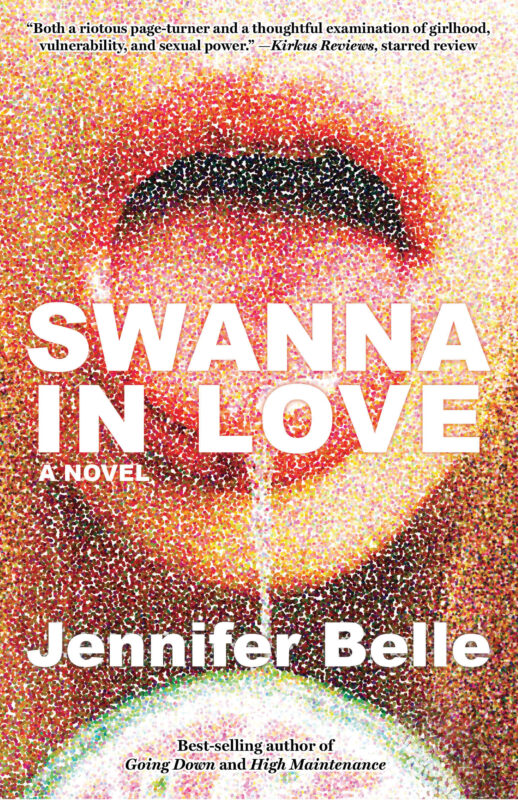

From Swanna in Love by Jennifer Belle. Used with permission of the publisher, Akashic. Copyright © 2024 by Jennifer Belle.