Susan Muaddi Darraj on Finding Inspiration in the Lives of Ordinary Palestinians

“I take my cue from them—these are my people, and their humble resilience will continue to inspire me.”

Every year, my aunt, who lives in the West Bank, ships bottles of olive oil to our entire family in the United States. It’s our share of the olive harvest—our inheritance from our grandparents and great-grandparents, who tended those trees since the late 1800s. My aunt handles it all, arranging for the olives on our family’s trees to be harvested and pressed into liquid gold.

When I was young, I loved hearing about how my aunt, my father, and their siblings joined my grandparents during the harvest. They’d surround the base of the olive tree with large tarps and swipe at the branches with long sticks, forcing them to release the olives. They’d sing songs to entertain one another, and when the sun rose high in the sky, they’d gather under the shade of the tree and eat their midday meal.

It’s an ancient legacy, unchanged for at least a century. In fact, one of their olive presses is the original one that our great-grandparents used.

I want to liberate Palestinian identity from the toxicity of middle-class respectability.

But since October 7th, olive farmers are being prevented from reaching their groves. Settlers shoot at, physically block, and generally terrorize them. This is nothing new; in years past, settlers have even uprooted, bulldozed, and burned centuries-old trees.

The olive harvest is October through November, maybe early December if you’re lucky. But at this point, it is over—and an entire community has lost its income, and its legacy.

And the olives are rotting on the branches.

*

These days, I’m reminded how impossible it feels to be a Palestinian in the diaspora. My social media timeline is more surreal than anything Kafka could have conjured up. On the one hand, I see a Palestinian child screaming, holding up a hand on which most of the fingers have been blown off. On the other, I see posts from American friends who are irate but amused that Valentine’s stuff is hitting the store shelves so soon after Christmas. Meanwhile, as a Palestinian Christian, I belong to a mourning community that refused to celebrate Christmas this year, even though the holiday originated with our ancestors.

Like I said, surreal.

Growing up in the United States as a Palestinian American, I’ve always lived in two worlds, although existing in this space now is more jarring than ever before. That’s because I am supposed to be, in this moment, while bodies in Gaza lay unrecovered under the rubble, promoting the launch of my debut novel.

I began writing this book six years ago. As a mother of three who works full-time, I have written fiction in the only way I know how: by squeezing even more time out of an already tight schedule. I belong to a group of people who write at 5am. I work until 6:30, at which time, my “real life” begins: I wake up the children, pack lunches, prepare my work bag, drop everyone off, and then head to my job. On a good morning, I will set the crock pot for dinner and start a load of laundry.

On one of these mornings, while the dawn was still splintering the sky, I began exploring a new character: a young Palestinian American man who is at odds with his father. Marcus is a cop, living in Baltimore. While Marcus and his father are both attached to their Palestinian roots, they are growing increasingly detached from one another.

As I wrote, morning after morning, I saw that Marcus’ father, a refugee, had one way of being Palestinian, an approach shaped by war and exile and poverty, while Marcus’s identity was quite different—it was deeply influenced by growing up in the working class, diverse city of Baltimore.

That’s how the book started, as a story about Palestinians dealing with the loss of their homeland, as well as with the urgency of living in a country that is, itself, fraught with class tensions and unable to confront its racist past. The novel grew from that seed, as I contextualized this father and son—I gave them subplots, I expanded on their relationships with others, I gave voice to their community, and so my novel came alive word by word and page by page during those six years.

As I wrote, I was driven by a passion to explore the lives of working class Palestinian Americans—the cousins of those olive farmers, of people who work the land and respect it.

Living in the United States, where the very notion of Palestinian existence is contested (I’ve heard “There’s no such thing as Palestine” enough for one lifetime), many Palestinians worked hard to depict our community according to upper middle-class standards of “respectability.” You were lauded for being a doctor, an engineer, a lawyer. Your home should be large and luxurious. Your clothes should be designer and your kids should be honors students. I get it—when your people are portrayed by the media as barbaric and uncivilized, the obsession with saying, “No, we’re not!” is intense.

And yet, I reject the idea that someone can be authentically Palestinian only if they’re upper middle class. What about those who landed in America and became part of the rest of American society that lives paycheck-to-paycheck? Are they less Palestinian if they delay an aching tooth because there’s no dental coverage? If they attend community college? If they work a job that leaves their hands and back aching at the end of the day? If their relationships don’t involve marriage and 2.5 children and a house with a pretty white fence?

I want to liberate Palestinian identity from the toxicity of middle-class respectability. Not many people write about the cleaning lady. Not many people write about the mechanic changing the oil on their car. About the immigrant mother who cuts coupons and can make a chicken breast stretch to feed a large family. About the refugee who quietly grieves when his children are financially stable but cannot speak to him in Arabic.

Erasure is a dangerous thing, but it’s why I have to believe that stories matter.

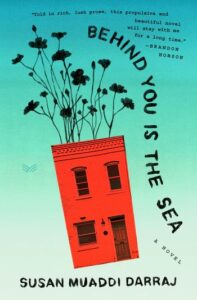

The book is titled “Behind You Is the Sea,” after the famous charge by Tariq ibn Zayid to his troops, when they landed on the southern coast of Spain. Having burned their ships behind them, he gave them no other choice by to go forward. Bleak as it is, it reminds me of the ways in which Palestinian refugees have had no other choice but to survive when they arrive in the United States… there is no path home, so they have to make it here.

*

I am relieved that my novel is finally making its way into the world. And yet, what kind of world is it entering? How can one think about books during a genocide, when the poets are being arrested, the writers ripped apart by bombs? Even the book world is violently suppressing Palestinian voices: how many instances of censorship have we seen? How many Palestinian writers have been either openly or—more dangerously—quietly canceled?

I had a school visit canceled shortly after the war began. I am the author of the Farah Rocks book series, an earlier foray into writing for children; my series is the first to feature a Palestinian American protagonist. I was scheduled to speak to elementary school students about becoming an author and the power of imagination.

The plans had been discussed in detail and the contract had been signed in September, but that suddenly didn’t matter to the organizers, PTA moms in this case. As they coldly told me that they’d see about rescheduling my visit later in the spring “or maybe next year,” I found their evasiveness insulting and infuriating. When I asked for more details, I was told, “We don’t owe you more details.”

I knew exactly what was happening.

I am Palestinian American author, and it was objectionable that students should hear me speak about the power of the written word.

Erasure is a dangerous thing, but it’s why I have to believe that stories matter. Writing is tedious but necessary work. Next year, the olive farmers in Palestine will be back at their trees, refusing to give up. I take my cue from them—these are my people, and their humble resilience will continue to inspire me.

__________________________________

Behind You Is the Sea by Susan Muaddi Darraj is available from HarperVia, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Susan Muaddi Darraj

Susan Muaddi Darraj is the author of A Curious Land, a novel in stories which earned an American Book Award and was a finalist for a Palestine Book Award. In 2018, she was named a Ford Fellow by USA Artists. A past winner of the Maryland State Art Council’s Independent Artist Award, she is also the author of Farah Rocks, the first children’s book series to feature a Palestinian-American character. She lives in Baltimore, Maryland, and teaches at Johns Hopkins University.