Support One Moment, Racism the Next: On Being a Black Nigerian Man in America

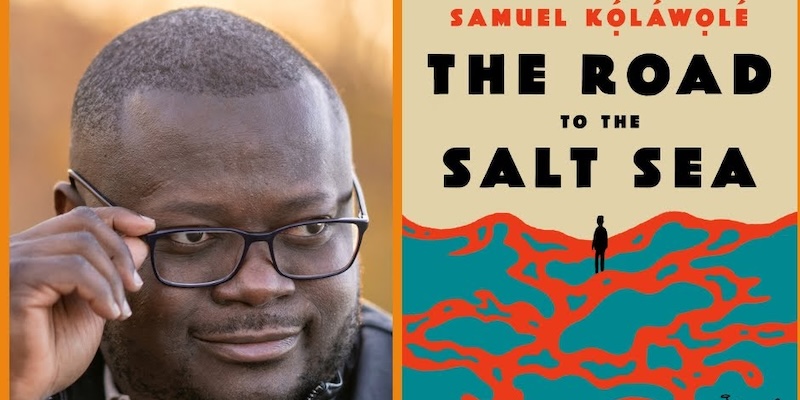

Samuel Kọláwọlé Recounts His Painful Entry Into the United States

After arriving at New York’s John F. Kennedy Airport, I proceeded to border control. I gave my passport to an immigration officer, and he asked me why I was visiting America. I told him I had been invited for a fellowship.

“You’re a writer?”

“Yes,” I said, barely getting the word out of my mouth.

The immigration officer said something about a book he had read while he scanned my documents. He took my fingerprints. I was too tired to pay attention, but I was happy to finally be in America for the first time. I passed through passport control without any problems.

After I retrieved my suitcases at baggage claim, I joined the long, slow-moving customs line. Moments later, a police officer approached me and told me to step out of the line. I was surprised but obliged without question, too fatigued to ask why he singled me out from the crowd.

I dragged my luggage behind me as he led me to a room with a long metal table. He demanded to see my passport and instructed me to put my bags on the table.

I was surprised but obliged without question, too fatigued to ask why he singled me out from the crowd.

“You are from Nigeria.”

“Yes.”

“Why are you in my country?” the police officer asked.

“I am here for a fellowship, sir.”

“What is that?”

I wasn’t sure what to say. I didn’t know if I needed to explain what a fellowship was or what would be a satisfactory response to his question.

I was particularly looking forward to this literary fellowship, which was awarded to me by the now-defunct Norman Mailer Center. Years of arduous work had culminated in this fellowship.

As a child, I aspired to be many things as one would at that age but never considered becoming a writer. Even so, I had a vivid imagination and frequently made-up stories in my head. My father was a researcher and my mother a voracious reader so there were stacks of books all over the house.

Then, in my late teens, I was plagued by debilitating depression, which threw me into the lonesome company of books and authors such as Stephen King, Mark Twain, Henry James, Jane Austen, and the Heinemann African Writers Series. This time of seclusion helped me come to terms with who I was. It was during this period of reckoning that I knew I wanted to write. After that, I couldn’t do anything else. I had found my calling.

In my twenties, I faced the painful realization that, given the lack of educational possibilities and infrastructure in Nigeria to support my aspiration and the general lack of recognition for my work as a writer, I would probably never be able to realize my full potential as a writer. There was a time when living in Nigeria was what I needed as a writer. The water, the air, the noise, and the experiences I inhaled nurtured creativity within me. Living in Nigeria made me the writer that I am today and even now the umbilical tie to my motherland is still very much intact. But I knew then that I had to leave.

In America, as in that detention room, I realized I still had to navigate the presumption of danger and guilt.

Receiving the Norman Mailer fellowship was my first sign that I could pursue my artistic career abroad. It was a harbinger of good things to come. I thought maybe I would one day make this place my home. I went to the US embassy not knowing if I would be granted a visa—American visas were said to be hard to get, especially for first-time applicants.

I was pleasantly surprised when the consular officer asked me just two questions and handed me the visa approval letter. I recall telling myself that perhaps the prestige of the fellowship was partly responsible for the ease with which I received the visa, with the most of it attributable to the divine hand of God.

Before I could respond to the police officer’s question, he grabbed a razor from a little handbag on the table and began ripping down the edges of my bag. I could not believe my eyes.

Despite my tiredness, I managed a firm tone: “Is there a problem, officer.”

“I am doing my job,” he replied.

“But you are damaging my bag,” I said after a pause.

“Nigerians often bring drugs into this country.”

When he finally stopped shredding my luggage and glanced up, I was simmering with rage. But I stayed calm. I had seen on TV what American police officers did to black guys. I just wanted to be on my way–I still had another long flight to Salt Lake City. Moments later, he let me go with no apologies and a torn bag.

In that room, I was confronted with the stigma attached to my green passport, which was partly created by the past transgressions of my compatriots, but I also sensed the racism that had dogged the United States since its founding. In that room, it didn’t matter that I had earned this renowned fellowship, or that I was in my house, in my small corner, when I received the email—I wasn’t a desperate migrant on the southern border, nor an embattled refugee seeking asylum. None of this mattered. What mattered was that I was Black.

In the years since my airport encounter with the police officer, I have questioned why I thought I was superior to the desperate immigrant and besieged refugee seeking asylum in that room. I have since developed a sense of kinship with those who leave their home countries in search of greener pastures or sanctuary, regardless of how they do it.

Three years after receiving that fellowship, I moved to America, and living here has left me with a longing for the sights, sounds and images of my motherland, so I wrote about Africa more than ever before as I had never been interested in exploring what it was like to be an immigrant in a foreign land. I was writing about what I knew, what was ingrained in me, and Africa was my canvas. Though they piqued my intellectual interest, my experiences in America have hardly found their way into my writing, in any form of prose—until now.

In America, as in that detention room, I realized I still had to navigate the presumption of danger and guilt. While enrolled full-time in the MFA in Writing and Publishing program at Vermont College of Fine Art, a white man approached our table when I was out to dinner with my classmates. He leaned over to whisper in my ear that I was not welcome in Vermont.

Vermont, the home state of Senator Bernie Sanders. Vermont, where on more than once occasion people crossed the road to avoid me. The unpleasant experience at the restaurant, however, was offset by the solidarity and support of my classmates and the college.

I’ve lived in the United States for more than eight years. I am now a professor in a top research university with publications and accolades. American is a place where I was encouraged to wander into the realm of possibilities, where my creativity found the space required to flourish, and my work is celebrated and rewarded.

But I am still a Black man in America, and in many ways, a foreigner. However, this is the country where I have felt most supported and free to make art. The kindness of friends has helped me in too many ways to count.

I’ve also poured into others and supported them in the same way that I was supported. I’ve had the good fortune to be part of strong communities. Here, I feel like I can inhale and exhale. But does this place feel like home?

______________________________

The Road to the Salt Sea by Samuel Kóláwólé is available via Amistad.

Samuel Kóláwólé

Samuel Kọláwọlé was born and raised in Ibadan, Nigeria. He is the author of The Road to the Salt Sea, and his work has appeared in AGNI, Georgia Review, The Hopkins Review, Gulf Coast, Washington Square Review, Harvard Review, Image Journal, and other literary publications. He has received numerous residencies and fellowships, and has been a finalist for the Graywolf Press African Fiction Prize, shortlisted for UK’s The First Novel Prize, and won an Editor-Writer Mentorship from the Word. He studied at the University of Ibadan and holds a Master of Arts degree in Creative Writing with distinction from Rhodes University, South Africa; is graduate of the MFA in Writing and Publishing at Vermont College of Fine Arts; and earned his PhD in English and Creative Writing from Georgia State University. He has taught creative writing in Africa, Sweden, and the United States, and currently teaches fiction writing as an Assistant Professor of English and African Studies at Pennsylvania State University. He lives in State College, Pennsylvania.