Oh well, she’s down the hill now, may as well keep going a bit, just a few more minutes, they’ll probably all still be asleep when she gets back anyway, though maybe Steve in his dressing gown, picking at his feet and doing the crossword from last weekend’s paper which is pointless but harmless – the crossword, not the picking, the picking makes Steve much more likely to have his scratching fingers bashed with some handy domestic implement, with the iron or the big orange pan, than he seems to understand. It doesn’t change anything, does it, doing a puzzle, you don’t learn anything or make anything. It’s exercise for the brain, Steve says, stops you getting dementia, running doesn’t change anything either, you have your hobby and I’ll have mine. Anyway it’s a bit weird, he says, the amount you run, it’s not normal, you do know that, you’re addicted. Fuck off, she says, yes I do know it’s not normal, normal is sitting on the sofa pushing cake into your face and complaining about your weight until you get type-two diabetes and they have to cut your feet off and then you die, no thanks. And she’s out and back before the kids are up, isn’t she, and if it keeps her fit and well into old age he should be grateful, she knows who’ll be looking after whom.

She must turn back. She can hear her children turning in their beds, scent their morning breath, feel on her fingers the roughness of their uncombed hair. There’ll be small bare feet on that carpet, small morning erections in dinosaur pyjamas. She’ll just go to that bay ahead, where the loch laps boulders and tree-roots under the fog, a tenderness between water and land that’s almost a beach, and she’ll pause there, a moment’s triumph before she turns back.

And she does pause and she does rest, inhales the morning through the rain, is still, lets water drip from her hair and her top. Here she is, under this mountain, beside this loch. Here, now.

But what’s another person supposed to do, if her heart stops? How would it help, to have a witness?

She sets off again before her muscles cool, before the body’s equations change again, back up the hill, under the trees, along the shore. There is a hiker, and another two, mummified in waterproof coats and trousers and gaiters, their rucksacks wrapped in tarpaulin. Just run, she thinks, take it all off and run, and she’s at the top of the hill above the car park when it happens again. Does it feel like a fish in your chest, the doctor said, patients often say it’s like a fish flopping. A bit, she’d said, watching him hold the probe on the bones above her breast the way they’d held it on her belly for the babies, thinking more like a bird, really, a flutter, a brush, nothing to worry about, nothing worth bothering the doctor for if she hadn’t collapsed at the top of the stairs at work. Turned out to be nothing, she said later, to Steve and to HR and to her mum, after the ambulance and the oxygen and the ECG. Nothing at all, I’d run that morning and not got round to breakfast, I’ve always been a fainter, remember when I was carrying Noah? No reason to stop running, one funny turn.

It’s more than a wingbeat this time, as she splashes through the brown puddle that now covers the whole width of the path. More, she thinks, grinning at the menagerie now imagined in her ribcage, at the entire damn food chain gathered in the chambers of her heart, more like a small mammal, something with hurrying feet. Smaller than a hare. A vole, doctor there’s a vole in my upper ventricle. One of these days, she thinks, one of these days, girl, and she pulls off her wet vest, balls it in her hand, picks up the pace, races bare-bellied in the rain past the tent and through the trees and around the barriers at the top of the holiday park, past the bicycles and the blue gas cylinders and the limp laundry and the old man sitting again at his open French windows with a cup of tea. Safety first, the consultant said, there in an overheated pink room with the machines resting between patients, we must think of your kids, they need their mum, don’t they, I’m afraid I must say there’s to be no more running. And if you really won’t take my advice at the very least don’t go far, don’t push yourself, don’t ever run alone.

But what’s another person supposed to do, if her heart stops? How would it help, to have a witness?

__________________________________

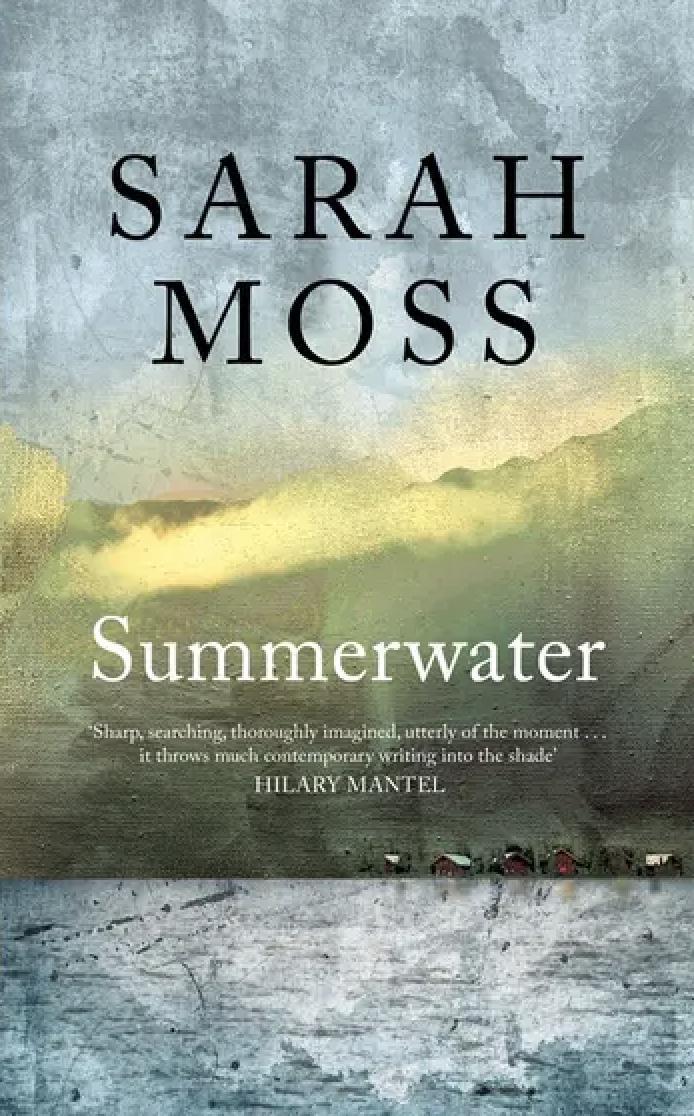

Excerpted from Summerwater by Sarah Moss, with the permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2021 by Sarah Moss.