When the sun goes down in Basilicata, the sky becomes a lung that coughs up blood, and the unsettling light makes you want to cough yourself. And before getting to the ravines, to the abandoned redbrick hotels and their infested pools near the gas stations with their lofty names, you have to pass by the oil stacks shining in the night and their red and green lasers that make you think of a prehistoric future— anything new in these parts ossifies quickly, changes to mineral, reflecting a deadened, gorgeous light—and then you have to go by a natural dam, a stretch of green water in the woods that the sun rarely finds and white smoke rises from in the morning. And it’s only after the curves of the dam, in the hairpin turns of water reappearing and disappearing with the complicity of the thin, dark trees, that the landscape finally opens almost to a desert, and the burnt amber of the sun transforms to something much rarer and hypnotic.

There’s a state road under the gaze of two rock spurs, and it’s here that I grew up.

The first place we lived was a two‑story house; the owner was the French teacher in town. As soon as I walked in, I asked what those metal hooks were in the ceiling: they were for hanging the pork, garlic, and dried peppers, but we never used them. By the time we left, there was an indelible stain on the floor from when my mother drank too much and was sick, the acids from her vomit imprinted on the tiles. The French teacher spread this story around, but we’d already found a new rental.

I came from asphalt, and in that town there was only stone.

The first day of school, I arrived in my light‑up Reeboks, fuchsia nail polish, and my hair combed back, and not in uniform. Right when I sat down the teacher said I’d have to dress like the other girls tomorrow. She had me sit in the middle of the others to make me socialize with everyone, but from that moment on I became an island, mortified by my self-sufficiency, yet continually seeking the affection of others. My brother had it worse: on that first day, his math teacher ripped out his earring, and he bled all over his desk.

I learned how to read and write in Italian, but always with a margin of error that made my teachers laugh. I said “stiro da ferro” for “ferro da stiro” (meaning “clothes iron” but saying nonsense), “bega” for “busta” (meaning “bag” but again, nonsense), and when we had to describe our favorite food, I drew a hot dog but called it a “frankfurt,” because that’s what we bought in Brooklyn, so even with this I was wrong. My fantasizing wasn’t just linguistic but also tied to class: whenever they asked us to draw our home, I’d make three bedrooms, a kitchen on to a living room, my mother’s painting studio, a playroom, a workout room, and a bar. Chrome surfaces, black leather couches, plants in the corners: the teachers took my drawings and had me come to the front of the class, where I was told that rather than The House I Want, the assignment was The House I Have, with me insisting it was all true.

I could read out loud perfectly, but I’d sometimes toss in a mispronounced word anyway because I just sensed what would happen if I didn’t make any mistakes: I already came from somewhere else and had no right—doing well in school would be an insult.

And so I stopped bothering with school and wound up skipping a hundred times in one year, enough days to guarantee I’d fail. The only reason I didn’t was that my teachers were afraid this would hold me back forever, would condemn me to teen pregnancy or a worthless engagement. I was “the daughter of the mute”—it wouldn’t be Christian not to show pity.

In the morning, I’d get my backpack, come downstairs and slam the door even if my mother couldn’t hear it, then I’d slip up to the attic with the key I’d stolen. I always wore a watch, so I could get back downstairs by one forty‑five, the official time to be home. Up in the attic I read Italian versions of Mickey Mouse and Grimms’ Fairy Tales, and old Elèuthera and La Tartaruga volumes, anthologies of feminist writings and prison songs. There was a wonderful story by Virginia Woolf where the main character called her husband a “lappin,” and I was convinced he’d really turned into a rabbit. And in Letter to a Child Never Born, when Oriana Fallaci imagines the main character during a trial, intent on speaking with her stillborn child, I thought that fetus was truly able to respond from its liquid‑filled jar, and I found this very touching. I was eight, and my mother never gave me any background about what I was reading: she, like me, always thought this was nonfiction, real life.

My mother can’t stand fiction. Whenever we watch something, there’s always a moment when she says, “But is it a true story?”—even if we’re watching a horror movie—and I have to lie because if I told her it’s completely made up, she’d lose interest and we’d never be able to do anything together again. Her “But is it a true story?” has plagued me forever.

To me, the book that changed everything was a Feltrinelli edition with an indigo cover. At the center of this cover was a heavily made‑up blonde dressed like Marilyn Monroe and walking along a shabby street past the fire hydrants. I snapped this book up for its title, Last Exit to Brooklyn, because I was homesick. It was extremely vivid, like I’d been shot through with contrast dye, revealing all my insides: I may have been a kid, but it felt like I’d been to that diner, the Greeks; I could see those dumpy apartment buildings—Grandpa Vincenzo had described them to me—and I understood why Tralala was acting like a prostitute: sooner or later she’d find the right guy. When they put their cigarettes out on her, filthy and sweaty, I was there to hold her. Through Hubert Selby Jr., I also discovered the importance of the dictionary: I had to stop reading until I looked up “faggot” or “Benzedrine.”

Mickey Mouse—Topolino—taught me Italian and gave me some lexical ownership; I would never have learned how to use the word “esilarante” (hilarious) or “scavezzacollo” (daredevil) otherwise; through gothic novels I was bequeathed “crepacuore” (heartbreak) and “consunzione” (consumption). And then there were those other books, my favorites, about street life.

In those years up in the attic, Fernanda Pivano became my best friend. My mother had Pivano’s translations of Kerouac and Fitzgerald, and these were careless and riddled with errors, apparently, which I’d only learn in college when everyone else made fun of them; it didn’t matter to me, though—I always made mistakes when I translated, and still do, because meaning doesn’t take on a stable form for me, and everything I think and everything I say suffers in the migration between different countries, bleeding the same way astronauts bleed when they’ve spent too much time in space and come home to constant nosebleeds in the light of day, back on earth.

Pivano knew how to hang out with bad boys and not fall into their bad behavior. Even if we came from very different families, I was grateful for her ungainliness and her capacity to fall in love with everything; it made me feel less lonely, and over time I convinced myself I wanted to be like her, awkward, manipulative, and in my mind, something of a liar.

Spring came, I opened the window, climbed out of the attic, and read on the roof. That’s where they found me. My math teacher and my mother were trying to knock the door down they were pounding so hard, but I didn’t hear because I was reading with my Walkman on. My teacher persisted; she went and got the neighbors’ keys to the attic and scrambled onto the roof tiles to come save me. I couldn’t go on like that, couldn’t keep covering my arms in Bic‑pen tattoos— tattoos were for far more adventurous people, sailors and circus dancers.

In the end, I had to force my mother to go along with my plan; bewildered, she couldn’t bear to see me cry and agreed not to send me to school, signing every excuse and letting me read what I wanted, though in bed, not on the roof.

__________________________________

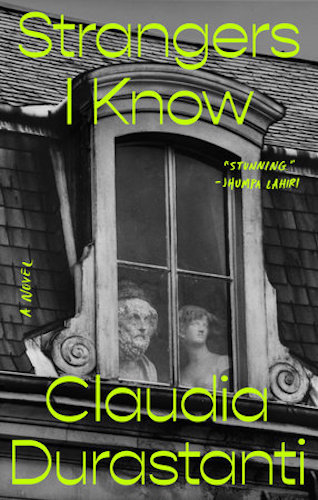

From Strangers I Know by Claudia Durastanti, translation by Elizabeth Harris, published by Riverhead Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2022 by Claudia Durastanti and Elizabeth Harris.