Storytelling Tips from the Writer of Blade Runner

Hampton Fancher: "If you're not in love with words why are you writing?"

If you’re not in love with words why are you writing? Wondrous, the books that explore the words, words that lead to ideas and ideas to expression. It is to your benefit to read a thousand books in your lifetime, and to get there you need to always be reading. Imagination is a greedy little pig that needs to be hand-fed. Several times a day. Fatten the pig.

If you’re not in love with the construction of words, trying to be a writer is as futile as trying to find water in a desert. By memorizing great writing—the lines, the speeches, the dialogues of the poets and dramatists—you’ll be keeping inside you the best company, the highest teaching. It will restore your heart, reward your mind, and provide immediate inspiration. Through recitation you can prime your faculties to write dramas wherever—on the subway, in the car, on the street, in the dentist’s chair. “If there is any substitute for love, it’s memory. To memorize, then, is to restore intimacy.” Joseph Brodsky wrote that.

Ink and blood. Ink means the actual writing, putting the story to the page. There is good ink, which draws me into the narrative, and there is bad ink, which loses me. Blood is what brings to life drama and depth of the story; the viability and plurality of its characters. You can have intriguing characters that exist within an otherwise flat or confusing story—that’s bad ink. You can have a good story with many dynamic elements, but acted out by characters who fail to pump the blood.

Explore ways to improve your writing of dialogue by asking what should I have said instead of what I did say. We walk away from situations all the time saying to ourselves, Damn, I wish I would have said this instead of that. That’s dialogue. Pay attention to it. Making notes on this stuff is one way you’ll learn to write better dialogue. Pay attention to how you say what you say in your head, trust that it’s the best way to put something to writing. And make a habit of writing these things down, otherwise you’ll be stuck in your head and that might drive you nuts.

Plot is fate. Fate is inevitable. There can be no fate without characters whose fate concerns us. So for now forget plot except how it grows from character—the plight of your characters.

Every principal character has an enterprise. Question it. If it’s not there the character won’t move. There’s got to be more than what just meets the ear.

Expression lacking the mandates of drama are worthless. There’ll be no incentive to turn the page if there’s no expectation of a destination. No matter how extraordinary the event described, it will only be ordinary if it’s not consolidated within a plight of a character whose action concerns us. What is it that impedes, compromises, jeopardizes the concerns of the character? Locate the actionable conflict. The trick is to impede the character, not the reader. Make it difficult for the character, simple for the reader.

Too much talk and not enough trouble is a bad thing to do. Exposition should be disguised, hidden in the trouble. Don’t be explaining things. Get rid of elaboration, keep the ball in the air, wake up the story. Draw a tree of your story. Climb the tree.

Mystery, discovery, a revealment. Is it achieved, even a little? A little goes a long way. But you’re in trouble if there’s no trouble they’re in.

Linkage: a chain of events, without a chain the wheels won’t turn.

The aqueduct. It’s got purpose. Its structure is a function of its purpose. To convey something that moves, moves from A to whatever letter you want it to end on.

The anticipation of an event: the principals have been put on notice. And we await the outcome. Something expected, something that threatens to reveal or change the fate of one or more of the characters.

Drama is contraction/expansion, momentum based on the frustrated necessities of the characters. Their woes, agendas, liabilities and strengths, virtues, hopes and contradictions.

Progression, being on the way to something, somewhere, leaving somewhere, wanting, needing something. Don’t dawdle, amble, or dillydally. Clarify, stay with the objective. There are exceptions, but if you digress, it better be pertinent to something your story or characters are up to. And digression better be fun. Above all, don’t fucking digress into anything intellectual. It’s action you want. It’s a pinprick even. Keep it simple, keep it felt. Language is secondary. But it also isn’t—don’t be stupid, write sharp.

The conflict between harmony and invention will lead you to the inevitable in unforeseen ways.

__________________________________

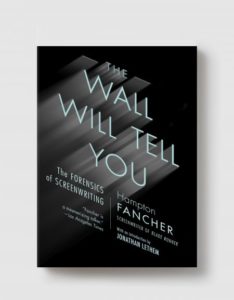

From The Wall Will Tell You. Used with permission of Melville House Books. Copyright © 2019 by Hampton Fancher.

Hampton Fancher

Hampton Fancher is a screenwriter, director, and former actor. Among his many credits, he wrote the screenplays for Blade Runner and Blade Runner 2049. A fascinating character in his own right, Fancher was the subject of the recent, highly praised documentary Escapes.