Slept poorly. The light from the green exit sign above my cabin door was too bright, and the ticking and cracking of the wooden building in the wind kept me awake. I get up at five thirty and shower, then make coffee. Manage to hotspot to my phone momentarily – reception very poor, but that is supposed to be the point of coming here – and download a short cheerful email from Alex, and a few others. Read some of them but can’t face answering any. I should have set up an auto-reply, but even that seemed an impossible task. I sit with my coffee at the little wooden desk and watch the sky slowly lightening beyond the spires of the pencil pines. I listen to the wind as it gradually drops.

At seven thirty I go, out of curiosity, to Lauds. (What else did I imagine I’d be doing here? Sleeping, I think. Deciding, perhaps, about Alex, my work. Crying. Hiding.) As I close my cabin door in the sunrise, the cold clean air moving down from the mountains, and the taste of that air, comes to me as if from childhood.

The sun is lifting and it streams into the church each time the big wooden door opens. The nuns enter quietly. The one with the walking frame arrives first. She might play the organ, though from my seat near the back of the guest pews I can’t see around the corner. Another lights the candles – one near their door, another by the lectern and two on the floor, at the foot of the big crucifix.

The singing is transporting, especially when they harmonise. One nun leads a psalm and the others do a repeated chorus. Lauds, like Vespers, goes for half an hour.

After this comes the Eucharist (which might also be called Terce?) at nine o’clock.

During Lauds I found I was thinking, But how do they get anything done? All these interruptions day in, day out, having to drop what you’re doing and toddle into church every couple of hours. Then I realised: it’s not an interruption to the work; it is the work. This is the doing.

*

The candles in the church are plain and white with a pleasant smell. Sort of herbal or cinnamony. A hint of incense, but not overpowering.

In the church, a great restfulness comes over me. I try to think critically about what’s happening but I’m drenched in a weird tranquillity so deep it puts a stop to thought. Is it to do with being almost completely passive, yet still somehow participant? Or perhaps it’s simply owed to being somewhere so quiet; a place entirely dedicated to silence. In the contemporary world, this kind of stillness feels radical. Illicit.

*

Later in the day I turn up again, at Middle Hour. It’s only about twenty minutes long. The same little tune is used for the various psalms, the same fatigue overwhelms me, and I can barely stay awake. Their singing is a chiming, medieval sort of sound: unexpected and unbalanced, yet melodious, in those thin reedy voices. They sing everything very slowly. It’s hypnotic. The words seem to make no sense. There’s a lot about evil-doers trying to destroy the psalm’s narrator. All day long they crush me. Foes and enemies, intent on massacre and annihilation. All this warbled by a bunch of nuns way out here on the high, dry Monaro plains, far from anywhere.

At the end of the Middle Hour, two approach the centre from opposite sides of the church, bow to the crucifix, then turn and bow to each other, then they leave. The next two arrive at the centre, bow to Jesus and then to each other. And so on, until there is nobody left.

*

Lunch is either to be ‘shared at table with other guests’ – no thank you – or a takeaway affair. I set off with my basket and a couple of containers from my cabin, down to the dining room. When Anita described this arrangement it sounded romantic, taking your basket and filling it with food. Images of wicker and chequered tea towels, Red Riding Hood-style. But it turns out the basket is the gaudy plastic kind used in the supermarket express lane. The decor (if that is what you can call it in a nunnery) is very simple, sort of innocent and somehow poignant. Like the house of an elderly aunt, but with crucifixes instead of ‘Bless this house’ plaques. Today’s lunch is thick slices of cooked ham, some bright yellow chutney, a plain green salad with a bottle of ‘Italian dressing’ nearby, and roast carrots, potatoes and parsnip, all a little hard. Plus a big vat of sticky-looking mashed potato that I avoid. The dessert is some kind of apple pudding. The pudding is good; everything else is ordinary. You wouldn’t want to eat this stuff every day of your life. The other guests – the two women, anyway; I haven’t seen the man – don’t look up when we pass each other. Which is fine by me.

Lunch is the main meal of the day, and we are to assemble our own dinners from one of the many packets or single-serve tins in one’s room. I’m saving two slices of lunch ham to have for supper with baked beans. The cupboards in my room are like some kind of storeroom from one of the country motels of my childhood. Everything’s packaged in individual sachets and servings – Nescafé, sugar, Vegemite, margarine, teabags. Teensy cans of Heinz spaghetti or baked beans, or tuna. Little boxes of highly processed breakfast cereal. There are biscuits in two-packs; Scotch Fingers, Jatz. And tiny individual packets of cheese slices in the bar fridge. Something makes me wonder if all this has been donated by some corporation or other. When I first saw all that packaging I couldn’t stop my tears coming, which was ridiculous. But something about the nasty little packets overcame me; it was to do with splitting everything into awful, unnatural fragments. The loneliness and waste of it. And a polluted feeling: even here, the inescapable imperative to generate garbage. Surely, if God exists, He could not approve of all this rubbish. Yet I have brought with me, quite against the spirit of the place, my own rubbish – blocks of chocolate, packages of salted peanuts, blueberries in a plastic carton, coffee, wine. He probably wouldn’t approve of that either.

Being here feels somehow like childhood; the hours are so long and there is so much waiting, staring into space. Absolutely nothing is asked of me, nothing expected.

*

I think of wandering to the shop to buy some candles. If there are any plain ones like those in the church, I would like to take one home. But instead of taking that three-minute walk I lie on the floor again and fall into a syrupy sleep.

Later, around four, I do visit the shop. There is nothing of interest to buy. Many hideous greeting cards, some of which bear religious images, but mostly they are just bad paintings of flowers. The Handmade Candles are especially ugly, garishly coloured and decorated with lumpy gold scrolls and astrological-looking designs. I do buy a plain sandalwood-scented candle, a plastic torch and a wooden cross. The cross has rounded edges and fits snugly in the hand. I am a bit ashamed of it. I don’t know why I buy it, except maybe as a mark of respect to these people, and as a kind of talisman, to hold and feel. It is for the body, not the mind.

*

Vespers again. There is one spoken element that disrupts the singing; ‘prayers of the faithful’ is the phrase that bubbles up from my childhood. ‘We pray for a marriage that is breaking down,’ one of the sisters says. I look at the floor. I think about Alex, but he’s free. He needs no prayers from me.

Then this: ‘We pray for all those who will die tonight.’

*

After my parents died – not together, though close enough in time to fuse inside my primitive self, inside my dreams and my body, into a single catastrophe – for many years I felt as though I were breathing and moving through some kind of glue. I could not have said this then. If someone had asked me how I felt, I would not have been able to answer. The only true reply would have been: I don’t know.

The day after I learned that my mother’s illness would not be cured I kept a doctor’s appointment in the inner city, where I lived then. When I entered the room and the doctor asked brightly how I was, I began to cry, and then – embarrassed – explained. She asked about my father, and when I told her he was dead she asked about the kind of counselling my mother and I had sought when he died. I was mystified. As far as I knew there was no such thing as counselling in our town.

She then told me I was clever, and right, to seek help now. But I only came here for a pap test, I said through my tears. She handed me a tissue box and said we would do the test another time. She asked me about my parents, and listened for some time. Towards the end of the consultation she recommended I see a bereavement counsellor. She herself was not a trained counsellor, only a general practitioner, and a specialist would be better able to help me. She wrote the name and address of the centre on a piece of paper.

Can’t I just talk to you? I asked her.

And so I did. I went to see her three times.

The doctor was big and square and imperious. For some reason her authority and her deep, practical kindness made me assume she was gay. She did not gush or emote, which was a relief. If someone had been openly empathetic, if I’d been entreated to elaborate upon the emotional terrain of what was now being called my grief, I would have been ashamed.

On my second visit, I remarked (embarrassed again by my tears) that it seemed my friends were deserting me, just when I needed them most. She was unsurprised. Your life has been stripped down to bedrock, she said. It’s not their fault; their lives are protected by many layers of cushioning, and they can’t understand or acknowledge this difference between you. It probably frightens them. They’re not trying to hurt you.

She didn’t say, Understand this: you are alone, but that is what I heard. I found it strangely comforting. She said again, I think you should call the bereavement centre.

The last time I saw the doctor, she seemed weary of me and my problems. She asked from behind her desk, a little testily: What is it that you want right now?

For this not to be happening, I said. I could hear the sullenness in my voice.

The doctor looked at me and waited for a moment. She seemed to decide on the simple, brutal truth. Well, it’s happening, she said.

I have always been grateful to her.

__________________________________

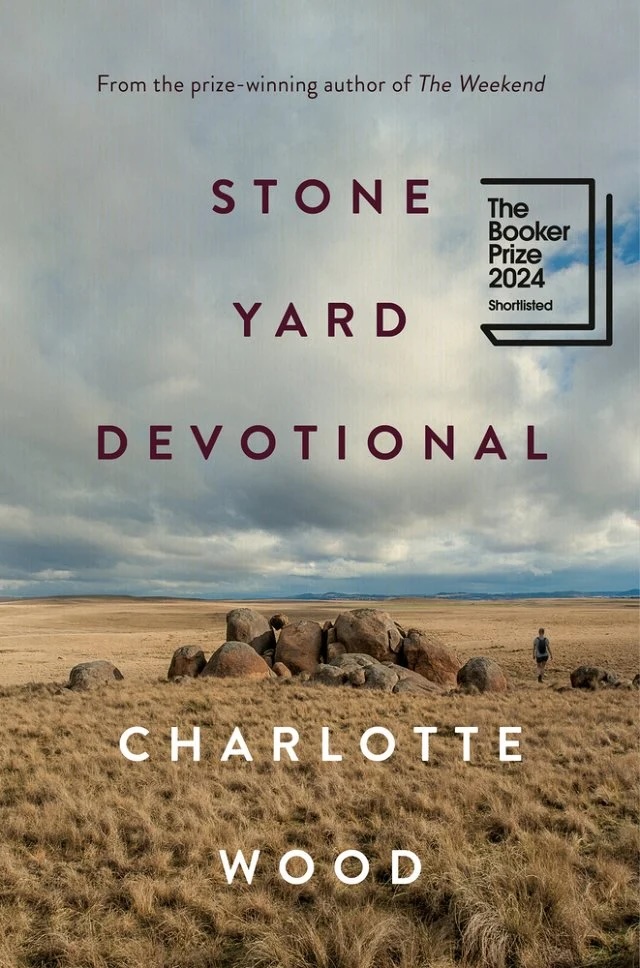

From Stone Yard Devotional. Used with permission of the publisher, Riverhead Books. Copyright © 2025 by Charlotte Wood.