Space Pastoral: Finding a New Literary Genre in the Slow Death of the International Space Station

Samantha Harvey on Sci-Fi Becoming Sci-Fact and the End of an Era in Technology

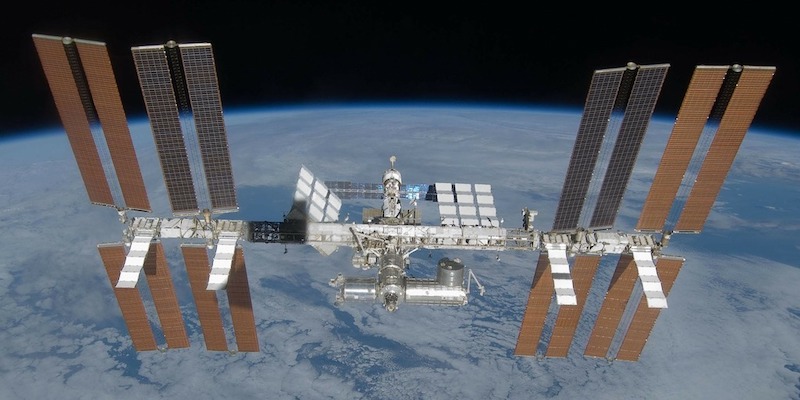

The International Space Station is a beguiling thing. Twenty-three years into its orbiting life, twenty-three years of continual human habitation, fifteen contributing nations, its story is an eloquent testament to international human collaboration. It’s the most expensive manmade object ever created, staggeringly complex and ingenious.

At the same time it’s become almost mythological in the human psyche—a point of moving light visible from earth, a silhouetted butterfly passing the moon, comforting in its unfaltering repeating transits.

As well as being technology and mythology, it’s also time capsule. Yes, new modules are added and there are constant innovations and renovations, but the original parts of the ISS are now well over twenty five years old. That’s a stately age for something bombing through low earth orbit at 17500 miles per hour, day in, day out—withstanding extreme heat, cold and solar radiation, pelted with space junk.

Marvelously, as a result, some parts of the Station are now in fact quite retro. They look more vintage than cutting-edge. The Russian segments, Zarya and Zvezda, are among the oldest, their internal parts fitted in the mid-1980s. Their walls are covered in oppressive green Velcro, handy for sticking things to in microgravity but now deemed a fire risk.

Many of the Station’s fittings are clunky and brutalist—not at all the corporate Disney-sleek lines of Space X tech that we see now. There’s a lot of disheartening beige. The “shower” is a pouch of water, a cloth and some rinseless soap. Lately, cracks have appeared in the Zarya module which a spokesperson has described, inspiringly, as ‘”bad.”

This splendid, sci-fi craft is orbiting its way into obsolescence. How tantalizing, from a writing point of view—the passing into nostalgia of something once trailblazing. Sci-fi, in becoming sci-fact, has become what I see as a whole new imaginative terrain, a kind of sci-pastoral. Space pastoral. With the outmoded Station and its gradual demise, an era ends. A technological and political era, but also a whole way of apprehending space and our relationship to it. A certain—if it’s not too simplistic to say it—lapse of innocence.

How tantalizing, from a writing point of view—the passing into nostalgia of something once trailblazing. Sci-fi, in becoming sci-fact, has become what I see as a whole new imaginative terrain, a kind of sci-pastoral.It isn’t just the spacecraft itself that has aged; some of its founding principles look kind of vintage now too. Consider that a quarter of a century ago the Russian space agency, Roscosmos, named one of its ISS modules “Zarya” (Dawn), signifying a new dawn in international cooperation in both geo- and space politics. Even if the relationship between Russia and the West was born more of expediency than love, still, it rattled on soundly enough.

And now, well—we’ve progressed (if that’s the word) to war and the complete collapse of that relationship. Where has that new dawn gone? Its last vestiges are orbiting the earth. Its ambitions are encoded into those hurtling titanium and steel modules: Dawn, Destiny, Harmony, Unity. Those cracking metal shells.

Enemies co-habit up there, cooperate there, share food stores, cut one another’s hair. Probably not for a great deal longer—Russia threatens to pull out of the ISS and it almost certainly will at some point—but for the time being the craft is a magnificent relic, a repository of disintegrated diplomatic dreams.

And then there’s the environment of low earth orbit itself that testifies to change. In 1961, a rocket upper stage exploded and its debris—about two hundred recorded fragments—was the first of its kind to enter into earth orbit. No human-made space debris had been created by a satellite breakup before then. Gradually this became more commonplace, but since the start of the twenty-first century, when countries all over the world started shooting satellites into orbit, the increase has been exponential.

Now there are millions of pieces of human-made debris orbiting the earth. They make human navigation complicated and dangerous; relatively often, the Station will slightly alter its course to avoid known debris, but the greater problem is the debris too small to have been catalogued—given the speeds of travel involved, a single fleck of paint can crack an ISS window.

What was once the new frontier, the pristine, humanless, ferocious expanse of low earth orbit, has become a rubbish dump we can’t clear up. We’ve done as we’re given to do—discover, domesticate, trash. Now consider again our time-capsule craft its determined orbit, speed-dodging old rocket payloads and spanners dropped by spacewalking astronauts. Can we really look at what we’ve done to the wilderness of low earth orbit and not feel a certain pang? A wish that this too had not been vandalized?

For that wilderness I feel the same strange, somewhat baseless—since I never experienced it—nostalgia I feel for medieval England, full of silent forests and eagles and wild boar. Something cellular in me longs for that again. This is what I mean by the imaginative field of space pastoral, the idea that space, too, has become subject to warm and probably useless thoughts of the good old days.

Yet meanwhile we set our sights on Mars. Space is no longer one thing; it’s the dusty past and cutting-edge future sharing surfaces with one another.

As for Mars. Our designs on that, too, lend the ISS what is beginning to look like a vintage charm. Granted that the ISS is a monumental and astonishing piece of science with specific goals, not least of which is to prepare equipment and astronauts for longer and deeper space missions.

It was always a step toward Mars. It was never an exercise in sentiment—but. But, it’s a craft that circles the earth from a distance of a mere 250 miles. It’s run collaboratively by national space agencies and everything that happens there (at least on the NASA/ESA side), every piece of science, all data, is in the public domain, ostensibly for the public good. It’s international, it came complete with a set of collaborative values on which it has delivered.

Contrast that to now, when space exploration is so commercially driven; every proposed endeavor in space travel is a part-privatized competitive effort not to circle and observe the earth but to get away from it, to the moon, which we plan to mine and build a base on, and ultimately to Mars. To get there first—fast! before Russia, China and India—to stake claims and to exploit resources, mostly for commercial gain.

The quarter of a century the ISS has spent in low orbit looks, by comparison, humble in its dedication to our planet. There’s something vigilant and devoted and democratic, even if just symbolically, in its steadfast orbit. Its observance of our weather, our animal migrations, our changing topographies; its ability, by virtue of its overview, to help contain fires and oil-spills.

It is by any measure a beautiful experiment that has almost served its time. In 2030 it will begin to be de-orbited and crash-landed piece by piece into the Pacific. It’s as if, as an entity, it perfectly projects humanity’s psychic shift from earthbound to extra-planetary as our curious restless spirit itches for the new.

What of those warm and probably useless thoughts of the good old space days? I do know that nostalgia can be a dull and forceless thing. I know too that on my gravestone will never be written he words: She Was a Great Adaptor. Left to me, humanity wouldn’t have progressed from caves and if it hadn’t already died out would be catching the odd rabbit which it would then feel bad about eating.

But in fact I found that this idea of literary pastoral was potent when I came to write about space. Here’s the slender whispering arc of our planet’s atmosphere, inside of which the auroras fret; behind which the moon distorts and the stars tumble. Here’s the dense crowded field of constellations at the Milky Way’s heart. Things that stagger you with their grand improbability.

And it seemed that if ever there were a vantage point for such writing it had to be this great space-hide we call the ISS, this ship that for almost a quarter of a century has been watching us and our acreage of cosmos with a faithful, quiet attention, just as the shepherd in the traditional literary pastoral watches his flock.

The Space Station as a new-millenium shepherd, inveterate wanderer, witness to loveliness, dependably circling. Its very presence in descriptions of space inscribes those descriptions with time and lends them vanishing points. I find this space-age relic, this embattled, dented dream-capsule, and everything it symbolizes, just captivating. On it goes, carrying at 17.5k miles an hour a lost era, an era that was once our golden future.

______________________________

Orbital by Samantha Harvey is available via Grove Atlantic.