Sorry Michelangelo, Da Vinci Was the True Master of the Human Form in Art

Charles Freeman on the Marriage of Beauty and Science in the Italian Renaissance

One can hardly deny Michelangelo a place in the history of observation when one looks closely at his Pietà (1498–9) in St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. However, his sculpture is always distorted by his desire to convey emotion rather than accuracy.

In the Pietà, Mary, holding the body of her thirty-three-year-old son among her voluminous skirts, is depicted as no more than a teenage girl. This is what gives the sculpture its pathos. His David is not well proportioned—the head and the hands are exaggerated—but his primary aim was to show the resolution and power of Florence, whose city authorities had commissioned the work from the twenty-six-year-old Michelangelo in 1501.

In his many tortuous representations of the nude, Michelangelo broke all the accepted conventions of classical harmony. Among them the Dying Slave, intended for the tomb of Pope Julius II but still unfinished after forty years, is a brilliant illustration of his internal frustrations. While his so-called “gift drawings,” made in the 1530s for a young Roman nobleman, Tommaso Cavalieri, to whom Michelangelo was deeply attached, are brilliant, they are disegni, compositions primarily designed for emotional impact rather than to demonstrate accuracy of representation.

Photo by GraphicaArtis/Getty Images

Photo by GraphicaArtis/Getty Images

The supreme genius of “scientific” observational art was Michelangelo’s older contemporary and rival, Leonardo da Vinci. Leonardo was born in 1452, the illegitimate son of a Florentine notary, and was brought up by his mother, probably Caterina Lippi, an orphaned fifteen-year-old, in the small hill town of Vinci in Tuscany. He moved into nearby Florence to begin an apprenticeship in the workshop of the painter Andrea Verrocchio. Leonardo had had no more than the basic education of the day in numeracy and literacy and does not seem to have mastered much Latin; throughout his life, he preferred to read vernacular Italian.

Perhaps one reason why he became so interested in the human body is that medical texts were by now often translated into Italian and so he would have been able to understand them. We know that he carried sketchbooks around with him, jotting down aides-memoires of whatever caught his attention. One text describes him as virtually buried by the reams of paper around him in his studio.

“No one,” in the words of the Leonardo scholar Martin Kemp, “covered the surface of pages with such an impetuous cascade of observations, visualized thoughts, brainstormed alternatives, theories, polemics and debates, covering virtually every branch of knowledge about the visible world known in his time.” In his surviving drawings one can often see how his mind works as he covers a page (from right to left) with the elaboration of ideas as they enter his mind, one drawing often infusing or influencing the next.

By the 1480s, in his early thirties, Leonardo had moved north from Florence to the opulent and scholarly court of the Sforzas at Milan. He was well trained, fully confident of his abilities and he must have felt that the city would give him more scope for his talents. There is another possible reason for his move.

Intellectual life in late fifteenth-century Florence was heavily influenced by Neoplatonism and so encouraged introspective thought, the search for truths that could only be grasped through meditation on eternal realities. This went against Leonardo’s own instincts and it seems that a more Aristotelian approach, reaching outwards to the material world, was prominent in Milan. It was certainly attractive to him. A surviving fragment from the 1480s confirms the markedly Aristotelian cast of Leonardo’s thinking: “All science will be vain and full of errors which is not born of experience, mother of all certainty. True sciences are those which experience has caused to enter through the senses, thus silencing the tongues of the litigants.”

He also wrote in his notebooks, again in contrast to those in thrall to the works of antiquity: “A painter who imitates the work of other artists instead of Nature herself, becomes Nature’s grandchild when he could have been her son.” Yet mere observation of “Nature” is not enough; there must be thoughtful consideration of the underlying structures of living things.

When Leonardo highlights the difference between those who paint as if they are simply producing a mirror image of an object and those who aim to capture its essence, his outlook seems to be moving closer to Platonism. As Ernst Gombrich, the great Austrian art historian, noted, Leonardo is the “most important witness” for those “convinced that the correct representation of nature rests on intellectual understanding as much as on good eyesight.”

After the degradation of the human form in so much medieval art, it was an important statement.

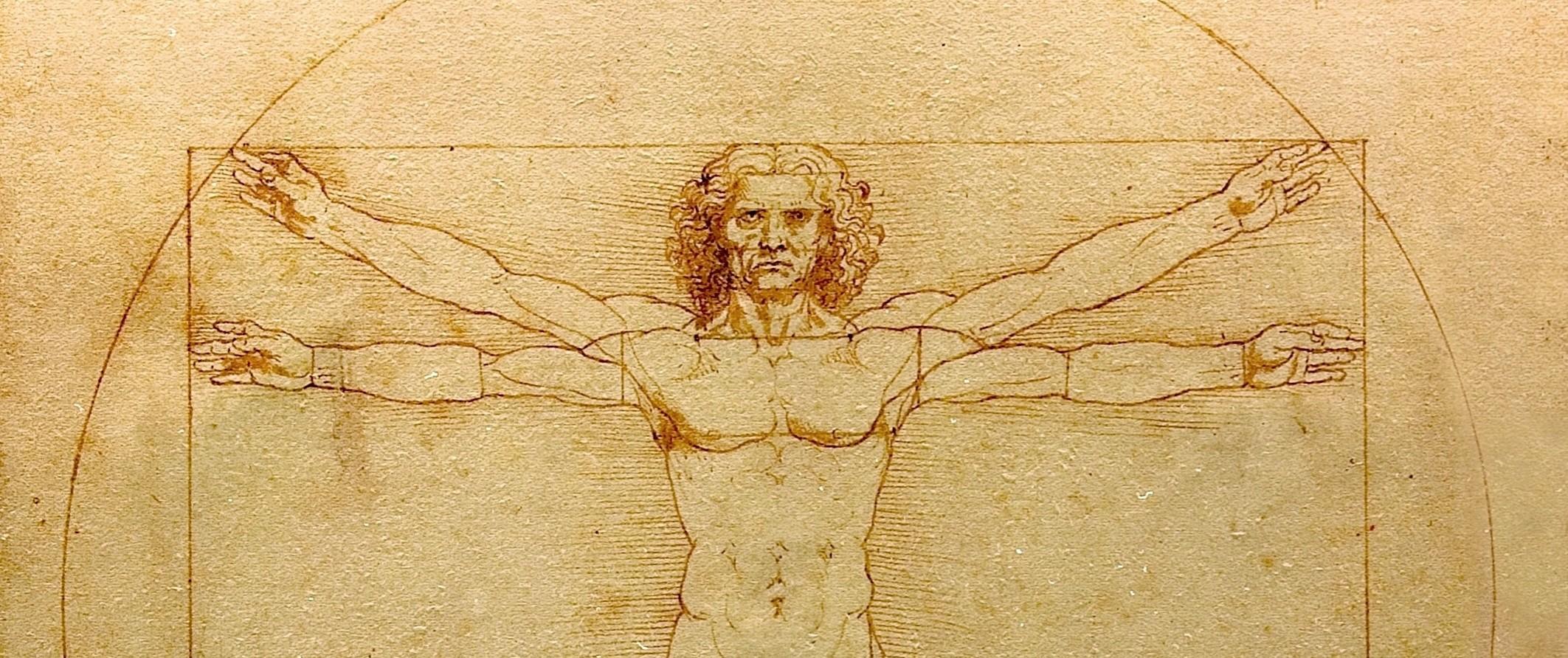

In the 1480s Leonardo produced his first anatomical drawings. He was still conditioned by outside influences, notably the belief that a human body was a harmonious whole. Inspired by the ideas of Vitruvius on proportion from the Roman architect’s text De architectura, he drew his famous “Vitruvian man,” probably about 1487. It remains one of the defining images of Renaissance humanism, a perfect male body stretching out to fill both a circle and square simultaneously. Of course, Leonardo recognized that this was an ideal body, perhaps seldom encountered in real life, so it can hardly be called a “scientific” illustration, but after the degradation of the human form in so much medieval art, it was an important statement.

In 1489 Leonardo described in a text, On the Human Body, how he would create a set of drawings that would show the progress of an embryo through conception to birth and then to the first year of life. He would then concentrate on the fully grown human body. The questions he asked are “scientific” ones. “Which tendon causes the motion of the eye, so that the motion of one eye moves the other?”

Never before had the human body been so rigorously examined. And Leonardo’s genius had endowed him with the artistic skills to match his intense curiosity. Among the fruits of this anatomical inquisitiveness was Leonardo’s studies of the human skull. These appear at first sight to be accurate drawings, but they too are created within an ideology that draws on ancient texts, in this case Aristotle and Galen, the outstanding physician of the second century ad.

It is clear from his accompanying notes that Leonardo was as much concerned with understanding the metaphysics of the human soul, its location within the skull, as in creating an accurate picture of the skull itself. “If man’s construction should appear to you to be of marvelous artifice, remember that it is nothing compared to the soul which inhabits such architecture, and, truly, be what it may, it is a divine thing.” This is typical of his intense desire to understand the issues he confronted in their most comprehensive form. As the distinguished Leonardo scholar Martin Kemp has put it: “No artist or scientist has ever possessed a stronger sense of man in motion as a sentient, responsive and expressive being.”

Photo by GraphicaArtis/Getty Images

Photo by GraphicaArtis/Getty Images

Yet inevitably, Leonardo was constrained by his sources and these appear to have conditioned his depictions of the human body. He drew on classical and medieval notions of the nervous system and shaped his studies of the spinal cord to represent them. Of course, he faced enormous challenges with dissection, as his corpses decomposed quickly in the warm climate. The dissected eye is notoriously difficult to draw as it “rapidly collapses into a gelatinous heap.”

It is evident that Leonardo allowed himself to be influenced by earlier conceptions of optics to make up for the inadequacy of his specimens. So while we can say that Leonardo showed a “scientific” approach to the human body, as yet he had not made any groundbreaking progress in the representation of one. It is not even certain, this early, that he was involved in dissection himself.

Even so, he was an inveterate observer of the natural world. It seems that there was no area of life that Leonardo did not penetrate and transform with his imagination. So quite apart from his achievements as a painter—his mural of The Last Supper, in the convent of Santa Maria della Grazie, Milan, even in its decayed form, provides an extraordinary example of how Brunelleschi’s rules of perspective, and the academic development of them by scholars such as Alberti, can be exploited—there are endless studies of movement in Leonardo’s work, swirls of water (a particular obsession), engineering gadgets, fortifications, ambitious plans to build a canal to make the River Arno navigable to the sea, and a famous map of the town of Imola, near Bologna. The Imola map, designed for Cesare Borgia, shows how Leonardo was able to adapt surveying techniques to produce pinpoint accuracy without depriving the town plan of an aesthetic life of its own.

There was no area of life that Leonardo did not penetrate and transform with his imagination.

Back in Florence by 1500, after the expulsion of his Milanese patron, Ludovico Sforza, from his court, Leonardo was restless and unsettled but no less productive. He was now devouring texts—his library contained 116 named items plus another 50 unclassified works. He had developed an interest in mathematics and possessed Euclid’s Elements, the most common primer for mathematical proofs, as well as works of Archimedes.

As was the case with Galileo after him, Leonardo appears to have regarded Archimedes as the greatest mathematical figure of the ancient world, and he explored Archimedean principles obsessively through his geometrical drawings. Like many other artists (notably Piero della Francesca; see p. 306), he appreciated the certainty that mathematical logic could bring.

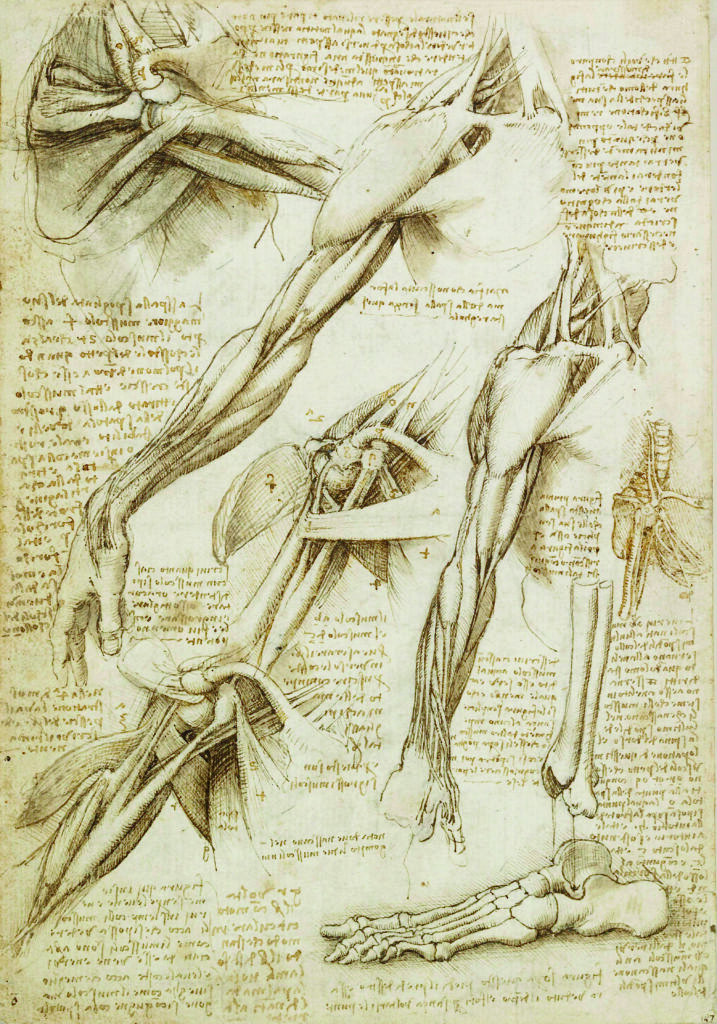

Leonardo’s preoccupation with the human body led to a burst of creativity around the year 1508, when he famously dissected a man aged over 100. Here he took an anatomically more sophisticated approach; his uncovering of the veins of the old man, withered and narrowed in comparison to those of a two-year-old child, led him to explore how blood and air were transported around the body. His own studies of fluids, many of them natural water flows, further informed these investigations.

Over the course of some twenty years, therefore, Leonardo had moved towards observations that broke free from ancient precedent. In his studies of the female body, now in the Royal Collection of drawings at Windsor, he attempted to depict the respiratory, vascular and urino-genital tracts together as a whole. While not wholly accurate, this ambitious juxtaposition of organs showed that he was now aware of just how complex the structure of the human body is.

Photo by British Library/Bridgeman Images

Photo by British Library/Bridgeman Images

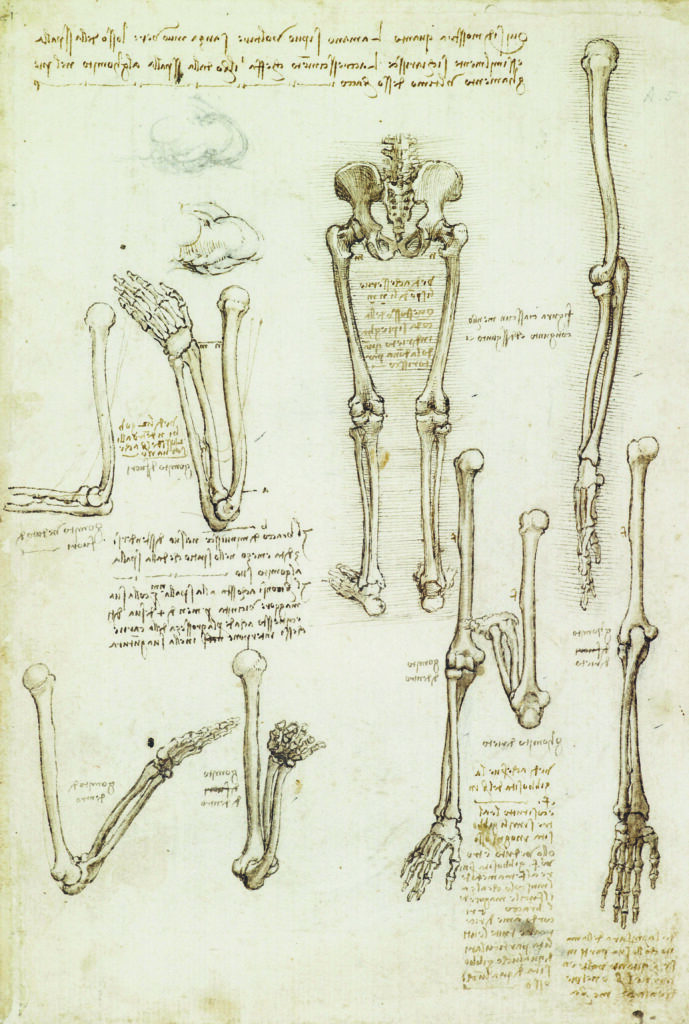

In 1510 Leonardo set out on a final quest to depict the inner workings of the body. The only way he could do it was to show the flesh, muscles and bones of each limb stage by stage as it was dissected. His aim now was clarity, so the different elements of the limb are first shown separately and then as they are when they are reassembled. This was an innovative approach and has been enormously influential in technical drawing. Leonardo exulted in what he had achieved in an age when anatomical texts lacked illustrations.

He knew that his drawings encompassed knowledge that a written text would never be able to provide. He had become a true empiricist, rejecting in the process the external “causes” of the organs, which the classical sources had defined for him, in favor of what he could actually see. As he put it: “Nature begins with the cause and ends with the experience: we must follow the opposite course, that is beginning with the experience and from this investigate the reason.”

Leonardo concluded his researches in 1514 with a magnificent series of studies of the heart of an ox. His determination to define cause and effect, to portray how the valves actually worked, led him to insist that it was essential to achieve the precision of a mathematician. Everything had to fit together as a working instrument. His greatest anatomical achievement was his accurate portrayal of the functions of the three-cusp valve at the base of the pulmonary artery. His depiction is so exact that modern research has confirmed his insights and his design is similar to the artificial valves used by surgeons today.

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Reopening of the Western Mind: The Resurgence of Intellectual Life from the End of Antiquity to the Dawn of the Enlightenment by Charles Freeman. Copyright © 2023. Available from Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Charles Freeman

Charles Freeman is an academic historian and the author of eight previous books. In 2005, he was appointed to the editorial board of the Blue Guides as Historical Consultant and has written the historical introductions to several new editions. He lives in Suffolk, England.