In the bitter year of 1988 I was banished to San Diego, California, to become a wife there. It was summer. I was buying groceries under the Yin and Yang sign of Safeway. In the parking lot, the puppies were howling to a familiar tune on a guitar plucked with the zest and angst of the sixties. I asked the player her name.

She answered:

“Stone Orchid, but if you call me that, I’ll kill you.”

I said:

“Yes, perhaps stone is too harsh for one with a voice so pure.”

She said:

“It’s the ‘orchid’ I detest; it’s prissy, cliché and forever pink.”

From my shopping bag I handed her a Tsingtao and urged her to play on.

She sang about hitchhiking around the country, moons and lakes, homeward-honking geese, scholars who failed their examination. Men leaving for war; women climbing the watchtower. There were courts, more courts and inner-most courts, and scions who pillaged the country.

Suddenly, I began to feel deeply about my own banishment. The singer I could have been, what the world looked like in spring, that Motown collection I lost. I urged her to play on:

Trickle, Trickle, the falling rain.

Ming, ming, a deer lost in the forest.

Surru, surru, a secret conversation.

Hung, hung, a dog in the yard.

Then, she changed her mood, to a slower lament, trilled a song macabre, about death, about a guitar case that opened like a coffin. Each string vibrant, each note a thought. Tell me, Orchid, where are we going? “The book of changes does not signify change. The laws are immutable. Our fates are sealed.” Said Orchid—the song is a dirge and an awakening.

Two years after our meeting, I became deranged. I couldn’t cook, couldn’t clean. My house turned into a pigsty. My children became delinquents. My husband began a long lusty affair with another woman. The house burned during a feverish Santa Ana as I sat in a pink cranny above the garage singing, “At twenty, I marry you. At thirty, I begin hating everything that you do.”

One day while I was driving down Mulberry Lane, a voice came over the radio. It was Stone Orchid. She said, “This is a song for an old friend of mine. Her name is Mei Ling. She’s a warm and sensitive housewife now living in Hell’s Creek, California. I’ve dedicated this special song for her, ‘The Song of the Sad Guitar.’ ”

I am now beginning to understand the song within the song, the weeping within the willow. And you, out there, walking, talking, seemingly alive—may truly be dead and waiting to be summoned by the sound of the sad guitar.

For Maxine Hong Kingston

__________________________________

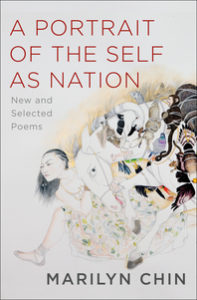

From A Portrait of the Self As Nation: New and Selected Poems. Courtesy of W.W. Norton. Copyright © 2018 by Marilyn Chin.

Marilyn Chin

Marilyn Chin was born in Hong Kong. She is the author of four previous poetry collections and a novel. Her work has appeared in The Norton Anthology of Contemporary Poetry, The Norton Anthology of Literature by Women, and Best American Poetry, among other publications. She is the winner of the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award, the PEN Oakland/Josephine Miles Literary Award, five Pushcart Prizes, fellowships from the United States Artists Foundation and the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, among other honors. Presently, she serves as a chancellor of the Academy of American Poets and lives in San Diego. Her latest book, A Portrait Of the Self as Nation, is available from W.W. Norton.