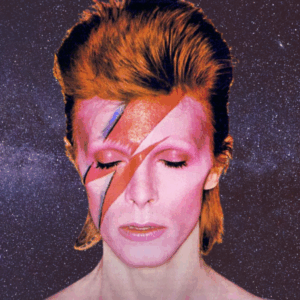

1.

The shop owner, by then, knew all about it: the girl’s hatred of elbows and stray pieces of hair; how her boyfriend disliked the taste of her lip gloss; how she referred to far too many body parts as “it.”

He knew which details she had made up to appear more experienced, even what she had swept over in an attempt to be coy. He listened to her, as bosses do, with hands folded, waiting through her blushes and her flights of qualifiers. The corners of his mouth and eyes remained still, like water.

The girl and the shop owner liked to talk. Once, they had been talking in the storage room, searching a heap of bubble wrap for a lost piece to a tea set, and he had gotten very close to her, blocking the door with his body. She had looked up and met the buttons of his shirt, tugging across his torso, and a flight of nerves had gone up inside her, like someone had smacked a screen door covered in moths. He had joked that someone might walk in and get the wrong impression, as if life could just be so funny.

It had come to this, surely, by the girl’s own indiscretion—not just her candidness, but some kind of postural lingering, something learned, but unconscious. She started to spend more time in front of the full-length mirror on the inside of her closet door, so that she could see all the way to her heels, which she raised off the floor. She saw less and less of her boyfriend, and when they spoke she thought she detected something in his voice, like the hook of suspicion. They broke up two months later, although it had nothing to do with the shop owner.

“If I were to ask you what your preferences are,” the boyfriend asked, “what would you tell me?”

The girl told him that he needed to be more specific.

“Your preferences,” he said again. It was an odd word for him to be using, she thought, but before she could answer, he continued.

“Well, mine are different. People already know.”

When she went to work the next day, the shop owner was there, feeding the wood stove. She told him about the breakup and their strange conversation and he turned his face to the fire, to hide from her, she imagined, whatever satisfaction he could not, for the moment, subdue.

“I was wondering when you were going to find out,” he said.

He stayed for the day, when he would have usually left her in charge, and chopped firewood behind the building, hauling armload after armload inside with his sleeves rolled up past his elbows. It was the sight of the sleeves like that—the meat of his forearms darkened by hair—that made her wonder if something had changed between them and if, perhaps, he was waiting for her to do something about it.

There was a large desk where she sat, in the back, by the stove. On one side of it, there was a stack of old magazines, and on the other, a shallow wooden box of loose postcards, mostly photos of old bridges and the fronts of hotels. The middle of the desk was kept clear for the exchange of money, the sliding over of small purchases in a folded paper bag. She didn’t know what put it in her head to sit there—some adolescent notion of sexual liberty—but she knew, the instant that he returned and saw her like that, that it was the wrong thing to do.

The shop owner dropped his eyes to the side and waited for her to climb down, then handed her the keys and told her to lock up in 30 minutes. She watched him go and heard the triple clatter of the bell above the door. There would be no more shoppers at this time. People did not like to stop roadside after dark, especially not to lurk through the twilight of scuffed velvet and sad lampshades. Still, she waited until closing time. She took the money from the cash register and recorded the profit onto a slip of paper. The drawer, now balanced for the next morning, was locked into the register, and the envelope of cash was placed in a small safe beneath the desk.

The next week, the shop owner said that he would be on vacation with his family and, since the girl would be off from school, it was up to her to look after the shop. He assured her, in his instructions, that there would be enough chopped wood for the fire until he returned. She wondered, briefly, how she must have appeared, on top of the desk like that. She knew better than to worry that he would speak of it, but she also knew that it would always exist, as a small loss on her part.

She worked diligently while he was away, even though she was alone and could have easily spent the time reading books or using the phone. She even dusted the stuffed emu that had remained unsold for so long that it had acquired a name, chosen by the girl who worked there before her, who had occasionally been mentioned by the owner with unwavering neutrality.

At the end of the day, she locked herself in to count the register. Because the shop owner was not there to collect it, the money began to pile up in the safe. Then one night, the girl unlocked the safe to find the money gone, replaced by a small brown box. For a moment she feared that they had been robbed overnight, but then she saw that the box had her name written across the top.

Allison.

Inside, under a sheet of crepe paper, was a necklace with an oval black stone. Formal. Something for a young woman.

2.

Allison met the man that would become her husband during their last year of college, then followed him to the city. He was always saying that he had friends there. She didn’t know why she was surprised when the friends did, in fact, exist, all together in little compartments over the street. Like the college boyfriend, the friends had been biology students, but they spent a lot of time playing guitars plugged into big amplifiers, which they once accused her of moving two inches to the right based on dust patterns. There had been shouting. The college boyfriend had flown to her aid, his ears turning pink with outrage. She had cried and cried from the commotion. The city was making her sick with its fumes, its pockets of hot breath and burnt rubber. She swore that the cupboards smelled like newborn mice.

“I have this thing where I can’t be around vomit,” the boyfriend had said the first time it happened and put up his hands.

It was the pregnancy that caused them to move back north, to be closer to his family. His parents owned a large property with a barn, but you couldn’t call it a farm; the horses were old, likely to trot back from the pasture favoring a hoof, and the chickens were slowly disappearing. There was speculation of a fox, as if such a creature in that area needed speculation.

Their decision to get married seemed not to rely on whether it was the right choice but rather on if his relatives in Canada could make it to the wedding, and if it was better to try to hide the belly or wait until after the baby was born.

“Things usually go back to normal,” said the woman who would be her mother-in-law. “Before the third one, at least. And by the fourth, you don’t care, just as long as it isn’t another boy.”

“These decisions—the birth, the wedding—as well as others, were made with the earnestness of dogs wanting to be good.”

It was a boy. They named the baby after Allison’s late grandfather, because it seemed like the right thing to do. He was born in January, in their own undecorated living room, with the rug rolled up, so that it would not be stained. It was how the baby’s father had been born, same as his brothers, all four of them. Ideal, maybe, in the old family homestead, with its hearth and its lambskin throws. But this was a one-story ranch, spare of furniture and not fully unpacked. The midwife had needed a pan to collect the placenta and they found one in a cardboard box, next to an unwrapped sushi kit and a ceramic cat with hearts for eyes. Come on, Mama, the midwife had said throughout the labor. Come on, like someone coaxing a stubborn cow.

By summer, they were married on his parents’ property, under a rented arbor. These decisions—the birth, the wedding—as well as others, were made with the earnestness of dogs wanting to be good. They painted the nursery yellow, because that was the color of the husband’s room when he was a boy. She could not dispute this logic, she knew, without weakening the mortar that had fixed together happiness and bumblebee yellow always in his mind. Even though, the way she saw it, bumblebees were mostly black.

In college, she had played the viola. She had always imagined herself in the symphony, with her straight, narrow back, wearing something thin, dark, and almost glittering. In the city, that may have been possible, but so far north, and now with the child, there were only opportunities in the early and late summer, when there were weddings.

Her husband’s cousin played the cello and knew a wealthy couple who had taken up the violin years ago, as an answer to their “echoing empty nest.” They formed a quartet and met at the cousin’s church, in the basement, playing “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring” between spines of stacked folding chairs.

The night before their first performance, she found herself struggling to find something to wear. Something around her middle had changed since the baby, who was now four months old, and there was a veiny tint beneath her eyes. She found the necklace with the black stone in the back of a drawer, still in the box with the crepe paper, and put it on for the first time. The shop owner had never spoken of it, and she had never felt an obligation to wear it for his sake. She had taken it in the way someone might receive a confession: not entirely certain whether power had been granted, or taken away. Still, the weight of the stone flat against her skin brought the small pleasure of knowing that she was once something unknown to the people there; to her son and to her husband.

The boy grew, healthy and cheerful, and often satisfied to play alone. Allison took advantage of this, retreating to her room to work through a bit of complicated fingering. Sometimes, talking to the boy, discussing what color spoon he should use, or whether or not it was a good idea to dip his teddy bear into the bath, left her voice feeling frail, caught in the pitch of adult to child deception. Something needed to be purged, and so she would work it through the instrument, following an earthy, resonant phrase, like walking a trusted path.

She worked, too. The husband brought in only so much as a high school science teacher, which had him in fits at the end of the day. Why, he wanted to know, was there always some teenager trying to tell him that whales were not animals?

“They probably just mean to say that they are not fish,” she suggested, even though she knew it would make his eyes clench in mock pain; his fight was wearying, the enemy ever more insidious.

It was her husband who got her the tutoring position at the high school’s library, which was better than her last job behind the counter at the coffee shop: being looked up and down by the worldly, latte drinking citizens, scanned by their eyes for general intelligence, sex appeal, usefulness; being asked, in so many ways, what had gone wrong in her life. But even with her pupils, she was always up against a sneer; another dirty attitude, waiting for her to slip up.

Her in-laws took the child during this time, which she was grateful for, even though it depressed her to hear them ask, every day, are you a good boy?, and to hear them say, watch your footing, be careful, until the anxiety was too much for him and he fell. That and they wanted to put him on a horse, which she fought outright, until they wore her down. It was an old horse, they said, a slow horse. Her husband had ridden it when he was a boy. All the boys had.

They saddled the horse on the first warm day in April. The saddle was a western style, large enough that mother and child could both sit without being crowded by the horn. The mother-in-law would ride ahead on her pony and the big horse would follow. There was nothing to worry about.

The husband’s family owned acres, stretching into the forest behind the house, but it was no use riding where there weren’t any paths, so they followed the neighboring fields. As long as they stayed next to the tree line, where they would not trample the crops, it was fine. Allison felt her shoulders relax. If she closed her eyes, she could feel down through the trunk of the animal beneath her, down to the planting of each giant hoof.

“A tractor,” said the boy, as they rounded a line of trees. He was excited to see a piece of machinery, like a familiar face in the wilderness. It was parked at the far tree line, by a woodpile. Allison could make out the form of a man, carrying out a repeated swaying motion with his body. As they approached, it was clear that the man was taking wood from the pile and throwing it into the back of a four wheeler. Every time a log would crash into the bed, the sound would bounce off the side of the tractor, doubling up in echo.

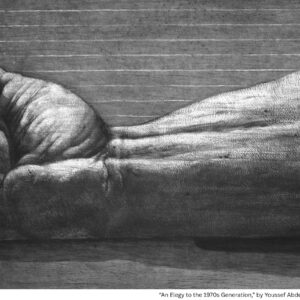

As they passed, the man threw in another log with a crash, causing the mother-in-law’s mare to bounce in annoyance, firing a little blast of warning from under her tail. In response, the big gelding buckled at the knees, then danced from side to side before leaping forward at a full gallop. The reins fell from Allison’s hands, the boy shifted to the side, and at the same time she had all the time in the world to think of what to do. There was no hope of stopping, so she kicked off her stirrups, hugged the boy’s arms to his body, and let herself roll off the side so that she would hit the ground with her back, her body a cushion for his. It was so very easy to maneuver. She felt like she could laugh.

The ground hit, and, as the air burst from her lungs, she had a clear sense of déjà vu, accompanied by a thought: This is where it happens. It has always been right here. It was as if she and the boy had taken the fall over and over again, recycled throughout eternity.

“That is just what Allison wanted: to come to the edge of a cliff and to back away, preferably on hands and knees.”

Her breath returned. The child struggled to free himself from her arms so he could watch the big horse thunder back to the barn, kicking up bits of horseshoe-shaped mud along the way. He was unharmed, unconcerned even. No one, for that matter, seemed alarmed. The mother-in-law, in pursuit of the runaway horse, could be heard whooping its name from the next field over. The man at the woodpile, who’d seen the fall, did not slow his swinging arms, nor did he call off his dog when it went to investigate the two figures on the ground. The dog licked the boy with a wet muzzle, pushing its insistent face back into them, no matter how Allison held out her arm.

They did not call it an accident. There was a lesson to be learned for the boy.

“He’ll have to get back on sooner than later,” said the father-in-law. “We wouldn’t want him to develop a fear.”

But that is just what Allison wanted: to come to the edge of a cliff and to back away, preferably on hands and knees; to see a rabid animal and to barricade the doors, call the fire department.

They told her that she was worrying too much. The runaway horse had been found after the incident, standing square in his stall, eyes half closed. Just a big marshmallow, they said. A teddy bear. We’ll just put the boy on his back, while the horse grazes in the field. As if that were somehow safer.

They lifted him by the armpits, red-faced and kicking, onto the back of the horse, who chewed, drooling gobs of green saliva.

“There,” said the in-laws, with some breathlessness. “Now he can get down.”

Allison watched the boy run back into the house, then sat on an overturned feed tub by the pasture fence. She wondered why everything was wrong, why she couldn’t just be thankful that everyone was alive, that bombs were not falling from the sky.

3.

A year later, she found herself separating from her husband. There had not been an affair, or even an argument; it was just that he had left for a long weekend to attend a job training and she had not wanted him to come back. It was the anticipation of his face, drawn in fatigue and pained by private failures; the dirty swill of his eyes scanning the kitchen, the living room, looking to see what had changed while he was gone, or what still had not been done.

The training was for science teachers, kindergarten through 12th grade. It was held somewhere in the Adirondacks, at a state park, in a small concrete building filled with beaver pelts, animal scat references, and cicada casings. The teachers slept in cabins and took cold showers in the outbuildings in their flip-flops.

“We learned how to dissect owl pellets today,” the husband said over the phone. “You know what they are, right? Tell me what you think they are.”

She had been about to throw a basket of laundry into the washing machine but set it down, standing over its armpit smells, the acrid shadow of his pillowcase that she’d washed twice already since he’d left. She sighed.

“It’s all the mouse parts that the owl can’t swallow.”

“Well,” he said, the word drawn in, a dumpling at the back of his throat. “The point is that you didn’t say owl poop, which is what half the people here said. Half. Can you believe it?”

“No.” She gave the basket a nudge and it slid almost the entire way down the basement stairs, hissing, like skis, before it flipped and bounced to the bottom. She knew that the stain on his pillowcase wasn’t really a stain, just the place where his head ground into the pillow at night, the one place in the house that would always smell most like him and would always remind her of a thumbprint in cheese.

He was upset to hear that she wanted to leave, but not as upset as she thought he would be. He told her to take the child and move to her hometown, only two hours away by car. He was certain that she would want to come back after some time alone. He would send her money. He would tell his parents that she was going to spend time with a sick family member, so that they would not think poorly of her. Everything would be fine. By the time they were finished discussing it, she was not entirely sure that the separation had not, in fact, been his plan all along.

Her parents’ house still had the aluminum swing set in the backyard from when she was a girl, with the same slide, always dappled by the repetition of rain and soil. Their rooms were made up for them, complete with a layer cake of towels laid out on the bed, like a hotel. The boy was adored with quiet gratitude. Her decision was never questioned.

“There were certain steps to be taken, she knew, for moving on, like chopping her hair, doing something drastic, but not too ugly.”

She found work at the elementary school, taking over temporarily for a music teacher who was having a baby. There was a lot of cardboard and glitter and toilet paper tubes, stopped at the ends and filled with beans for shaking. There was no epiphany, no rush of dark pleasure now that she was on her own; just “I’m a little teapot” during the day and dinners at home of macaroni and cheese with little cubes of hotdog.

When she first took out the viola, it sounded dry from the travel. Her mind would drift; her bowing arm would become heavy. There were certain steps to be taken, she knew, for moving on, like chopping her hair, doing something drastic, but not too ugly. Her mother urged her to meet people, to “build a foundation,” but she would not; she was comfortable, for the time, living in a blind spot, off the grid of where she had pictured her life heading.

And then one day, in February, a change occurred, marked by a dream. It was one of those dreams where very little happens, but something is injected under the surface, into the commotion of life, drugged by sleep. When she woke, she remained in bed for some time, seeing his face in the rumpled darkness, while falling snow and ice hissed against her window.

In the morning, she was still stirred, but with an added dint of sadness. Her husband had called her the night before, like he did every Sunday, to ask about the boy and to inquire, nervously, about her plans. He told her that he hadn’t felt like seeing anyone else, meaning women, and then waited a long time for her to respond. He talked about his students. He wanted to know if she had heard that narwhals were in fact mythical. Did she know that brown cows can only make chocolate milk?

She focused on the slight breakage at the end of his questions, the great effort he put into pronunciation that could only be described as “toothy.” She had tried to imagine that this would be the last time that they would ever speak, even though she knew he would call again next week. She had imagined what it would be like to see his traits emerge in the boy as he grew, traits that she may or may not have taken for granted in the past. But there had been only weightless, drifting apathy, like the fatigue from artificial light.

She went outside to clear the snow from her car and then work on the layer of ice on the windshield wipers. You could sometimes forget that there was something to be uncovered once you got to chipping and scraping, as if the point were to just keep working until you hit the ground. Exhausted, she opened the car door and sat, freezing, behind the wheel. She looked at the gray sky, the corroded white of birch trees, through the hole of visibility that she had cleared on her windshield.

In her dream, the shop owner had been sitting behind the desk by the open stove, the same large desk that had been there when she worked for him, years ago. He was writing in some kind of financial log with his sleeves rolled up and his arms glowing in the light from the burning coals. He would not look at her. He would not speak to her.

She turned the key in the ignition and was blasted by cold air. Inside the house, she knew that her mother would be making coffee, while the boy ate his cereal in the kitchen, scrutinizing the cardboard box (why he could never put that kind of concentration into a real book, she would never know). If she left now, they might not even notice that she was gone.

By the time the hot air kicked in, she had already taken the exit off the highway and pulled into the gas station across the road from the old antique shop. She would wait for ten minutes, she told herself, and if she did not see the shop owner by then, then she would go home, call in sick to work, and come right back. She would sit there in her car all day if that is what it took.

She prepared herself to wait, but when she raised her eyes, he was already there; just a shadow behind the window of a pickup truck, rolling to a stop in the gravel parking lot in front of the shop. The man emerged, hulking in a gray overcoat, and walked to the shop door, where he kicked loose an icicle on the gutter. Her first impression was, not surprisingly, that he looked older—he had been in his fifties when she worked for him, almost ten years ago—but he still had the same broad carriage, the same security of strength. She could see his beard, now fully gray and trimmed close to his jaw. The rest of his face was hidden beneath the furred brim of his hat. She watched him unlock the door to the shop and disappear behind it, imagined him switching on the overhead lights and then going straight to the wood stove. Something knocked around inside her chest, half-winged and terrible.

She went about the rest of the day distracted, unable to focus on her regular tasks, as though she were still in that frozen car, peering through the narrow hole of cleared ice and snow. At school, she unlocked the storage closet and dragged out the xylophones and frayed squares of carpet for her students. She let the time pass in the clumsy gallop of misplaced mallets and little voices off key. When the last school bell rang, she drove home, stopping by the neighbor’s house on the way to pick up the boy, who had been there since lunch. She must have strapped him in the car seat, she must have put his mittens over his hands, for although she didn’t remember doing so, he was there, dressed and asleep, by the time she pulled into the gas station again. The antique shop across the road did not close until six and it was not yet four, so there would be little chance of seeing him. Still, she sat, warming the tips of her fingers in the heating vents, just in case she caught a glimpse of shadow, some small sign that he was inside. That was all that she needed.

Half an hour passed. From where she was parked, she could see the items on display in the window—an iron ribbed trunk, a stenciled child’s sled, a mirror reflecting the purpling clouds overhead—and behind them, a sliver of depth, the only suggestion of the space beyond. So far, nothing had crossed it, even though her eyes had remained fixed, pooling with concentration. When the child woke, he wanted to know where they were. He was hungry and cold. She turned on the radio, she dug through her purse for a candy, but the boy only began to cry. Defeated and annoyed, she drove home, determined to return to the spot in the morning.

But the next morning, she felt differently. With horror, she recalled the events of the day before and found each moment distorted by something that she now felt no connection to. Toward the man, the shop owner, for whom she’d waited so long to see cross behind the window, she felt only disgust. She would never go near the place again.

Weeks passed and the strangeness of the day had not returned. A freak reaction, she told herself, caused by stress, or the long winter. She developed a better practice schedule and, through regular use, her viola regained its familiar give, ripened like a spot of hardwood floor warmed by the sun. When she played, she dipped into something that was always streaming, moving like ants through the veins of a colony. There, she was all feelers, little bits of armor, a million tiny, uncrushable hearts. They poured from her instrument and found their way in swarms through the cracks in the walls, slipping outside beneath the skin of the trees, down into the earth, where the egoless are.

And then, on a day in March, she woke before sunrise and could not fall back to sleep. Her mother’s little dog was up, dancing its toenails against the kitchen floor, so she put on her jacket and clipped the leash to its collar. Outside, it was unseasonably warm. Her muscles relaxed and her mind wandered. She wished that she had someone to call other than her husband, whose conversation was still irritatingly stoic.

“She wanted him to ask her about the people in her life who’d hurt her and for him to be surprised at her answer, impressed by the depth of her life before him.”

“We lost another chicken at the farm,” he would say. “Maybe you will have an answer for me by spring.”

She had tried to speak to her husband about the incident with the horse after it had happened, about how time had slowed and she had maneuvered her body to protect their son. About how she had felt that it had all happened before. This is where it happens.

“Adrenaline,” had been his response. “An amazing thing.”

But that wasn’t what she had wanted to talk about. She knew the mechanics of it as much as anyone. What she wanted was for him to ask her about something ridiculous, like her past lives, or if she ever flew in her dreams and, if so, whether she flapped her arms or kicked her feet. She wanted him to ask her about the people in her life who’d hurt her and for him to be surprised at her answer, impressed by the depth of her life before him. It wasn’t about revealing her soul—a word that she wasn’t sure if people were still using seriously, like Pluto—but about giving the tangential a place in their life; casually but also mindfully, just as one might start putting a feeder out for birds in the winter.

She let the dog put its weight into the leash, as if she could get away with following it, across town, to where the houses had shapelier gardens and names on the knockers; to the street where the shop owner lived with his wife. The windows of the house were thick with sleep, with gray-blue deafness.

She took a seat on the curb directly across the street from the slope of his front yard, where the crocuses were already coming up along the lattice under the porch, little wet paintbrushes of purple and yellow. The dog sat on its stump, obediently, and looked with her, working its nose against the wind. There was no bench, no view, no reason to be there. She should not have been there, but she waited as the cars came with their headlights spreading over the road, and as birds dropped down and picked over the new ground. She waited for the light to turn on and when it did, downstairs—a little yellow heart, beginning again—she stood up and walked back.

When she returned to her mother’s house, the boy had just risen and was looking for her with a watery, worried stare. He wanted her to pick him up, up, up, as if to break through the atmosphere.

4.

She wore the black necklace to the shop owner’s funeral that fall. When she read his name in the obituaries, it did not register immediately. Was that really how it was spelled? Was that how it looked on paper? Because it was not how it felt, spun into malleable lint inside her mind. She wanted to know if it was him, or just someone with his name.

She was shocked to see the open casket—as if it were something that he had consented to—and it shook her opinion of him, just a little. She considered reminding her husband, who still called every Sunday night, that she wanted to be cremated, but then wondered if that knowledge would somehow tie her permanently to him, “until death.”

She remembered, as a child, dreading the body of her grandfather, her son’s namesake—not because of its appearance, but because she feared that she would be expected to say something to it, a prayer that she had not been taught. Her six-year-old cousin, the only other child attending the wake, had huddled by the fireplace, shivering. I’m cold, he told the grownups, I’m too cold, and they shook their heads. You can always count on that one, they had said. Oh yes, you can always count on him.

Years later, during some unremarkable moment—sitting in school, or riding in the car with her feet on the dashboard—it had suddenly occurred to her that her cousin had been afraid of the body, but did not want to admit it. What a terrible world, she had thought, and still felt, from time to time, that a boy, who was probably scolded for saying things like “cross my heart and hope to die,” was expected to see a corpse and act accordingly. Stepping into the funeral home, she vowed silently to save the children, should there be any inside.

There was one, a little girl wearing a purple jumper over a black turtleneck, who swung her legs from a tall armchair while reading a paperback. She did not appear to need saving. Allison stood in a line to the casket. One moment, she was looking at the spider veins at the hemline of the skirt in front of her, and the next, she was over his face. Some nearby vent was pumping cool air, which, although odorless, she wanted desperately to avoid, like the puff of wind from under a train. The face before her looked pained, as if caught in the state of being about to swallow. A poorly executed clay figure; a creased sock at the bottom of the laundry basket. She felt the pressure to move along, so that someone who actually knew him could gaze, move their lips.

And then she was in front of the man’s wife, not realizing that she had entered a second line. The wife had an open expression, a face of recognition, perhaps left over from the person who had been in front of her just before. The skin around her eyes was gluey, caked-over red.

“Oh, Allison,” she was saying. “Allison, Allison, Allison. Look how you’ve grown up. Thank you for coming.”

The line moved on. Conversation trickled as people willed themselves into circles, trying to place their connection to each other, like stringing beads.

“Do you know how it happened?” It was the girl in the purple jumper, leaning back in the chair, her arms spread wide in ownership.

“No,” said Allison. “Do you?”

“My mom said that his heart kicked it, but I don’t believe her because my dad looked at her weird when she said it.”

“You’re not afraid to be here?”

The girl swayed a little, dreamily.

“No. Grandpa looks like the trees when they talk in cartoons. They talk and then their faces just go back to looking like bark. That’s what I say.” She curled back the front half of her book and forced a sigh.

The woman walked home with her hands plunged into the pockets of her cardigan, digging into the give of the wool. She waited for a weight to lift, or to descend, some indication that her life was affected by the man’s death, but felt only the pain of her shoes where they rubbed, up and down. It was a Friday afternoon, still two more days until her husband would call, leaving openings in his speech, places where she knew she could lay out her decision and have it met tactfully and with absolution. She stopped to look up at the glint of a passing jet, which had been roaring inconspicuously through her head for some time. How lucky I am, she thought, watching the plane blink into the clouds, to still have someone on the other end, waiting for me to make up my mind.

This story originally appeared in New England Review. See the rest of the 2017 O. Henry Prize stories here.

Genevieve Plunkett

Genevieve Plunkett’s stories have appeared in the New England Review, Willow Springs, and Mud Season Review.