No one ever hears music past the first time. Everything after is just a high-fidelity echo, fading already, even in the midst of our own incarnations. Then we’re born and we walk around for a little while, humming, whistling, tapping our feet, trying to find the beat, the note, the sound. Anything to get us back to the source, just one more time, before we start the slow, certain process of dying to ourselves, life shrinking little by little, the echo growing fainter and further, until one day it falls silent. If only we could hear that song one more time.

I looked for music everywhere: in basements and VFW Halls, in roller rinks. I learned the guitar and fell down the stairs holding it in my hands. I sang in church choirs; I sat through funerals just to hear the organ play. I started a band and screamed into rusty microphones, jumping around the stage until my shoes filled with blood. But it wasn’t enough.

Sure, sometimes I’d close my eyes and the band would play and I’d feel a pulse in my whole body and my mouth would drop open until I was the O in holy, but it only lasted for a moment. It was so big and memory is so small. I couldn’t contain it.

I once saw a man get shot outside a club we had just played, somewhere in Arkansas. It sounded like God’s own snare drum at the beginning of time. An orchestra tuned up in the scattering crowd. The incident’s conductor raised his hands in the air. I was sure it was the start of something special. But the music never came.

I tried everything. I turned up the stereo and stuck my head inside the speaker’s cone until my whole skull rang. I stuffed my ears with cotton and pressed my chest against the megaton subwoofers beneath the festival main stage until my body threatened to shake loose.

I fell back on the ways of science, the teachings of my chemist father, trying to isolate the most essential properties of song by process of elimination. First, I threw out any record with words. Being a singer myself, I knew how useless they were. After that, it was anything with guitars, then drums, and so on, until I only bought records that sounded like the faint hum of empty train tracks at midnight.

Things went on like this for the better part of three decades—my life spinning around me like a record on a turntable, the world getting smaller and faster as the needle moved closer to the center label—until every recognizable tone and timbre fell away and all that was left was the static and skip of the runout groove,

ca-chic-ca-chic-shhhhhh

ca-chic-ca-chic-shhhhhh

Over and over again.

*

After watching my band implode on the last tour of our career, I spent a couple of days wandering through San Francisco, drinking coffee. I had almost entirely given up on music. Still, I walked around, humming, whistling, tapping my feet out of habit more than anything else. It was in such a state that I lost myself in an upper room at City Lights, flipping through the writers of my youth: Burroughs, Corso, Ferlinghetti. Those old junkies sure knew how to make a point, even though they were probably full of shit, too.

I picked up a copy of Howl that must have been printed earlier that morning—the tang of ink was fresh like bitter grapefruit. It had echoes between its covers. Earlier voices, earlier thoughts. There must have been a time when its ideas were new and pure, but this was just a reprint. Already, I could feel it breaking down in my hands. I walked to the window and turned the book’s pages until I saw a phrase that produced an immediate physical reaction in me: listening to the crack of doom on the hydrogen jukebox. I wanted to believe in the existence of that sound so desperately that it felt like being stabbed. For a moment, I held the phrase in my mind, letting the discomfort build, then I closed the book and threw it out the window.

Unfortunately, the staff saw me do it. After I paid for the book, I tried to explain myself. I had thrown the book out the window as the result of an aesthetic decision. Staying in San Francisco, rather than going home, had been an aesthetic decision as well. Increasingly, these were the kinds of choices I felt capable of making. The store’s manager struck me as an incredibly kind, patient man. As he escorted me outside, he softly confided that he understood just what I meant.

Howl was waiting for me against the curb. It looked better having had the shit kicked out of it. All echoes should have a few bruises. That’s just life: A thing happens once and it’s pure, everything after is a facsimile, which degrades. But surely there must be a way to follow an echo backward into an original state of grace. At the intersection of unrelated things, couldn’t there be a place where echoes might collide, briefly making something new?

My mind accelerated without a weight to pin me to the present moment.

Out loud, I said, “I am going to kill myself.” But the aesthetic was wrong. I picked up Howl. Each line depressed me more than the line that came before it. In this very city, Ginsberg had found the original music. He had heard something. He had lived. But that was such a long time ago. I dropped the book and kicked it down the sidewalk. Wind blew through a pile of garbage sitting at the curb. A voice called out to me.

“You want to know the secret?”

The garbage sat up, kicked some newspapers from his body, and pointed to the book.

“I can show you.”

I didn’t have anywhere else to be, so I followed him.

*

I went looking for the sound at the bottom of a bag of heroin. We traveled from the bookstore to Kearny Street, then through the Tenderloin, and down the 6th Street corridor, where meth heads paced the corners, tapping worn-out sneakers on the pavement’s loose keys. Here, clocks ran a little faster, sunlight burned a little brighter. But we were looking for something else. At the BART station on 16th and Mission, figures materialized in the shadows, stepping out of corners to see if we wanted a taste.

My companion held out his hand and said, “This is the guy.”

I gave him all the money in my wallet. An exchange took place. Church bells were ringing. Somewhere in the station, people were drumming on plastic buckets. Down the block, a car horn blared. Trains were approaching. My mouth began to water.

“Do you hear that?” I asked him.

It got quiet as the dealer slipped something into his palm. He cupped both his hands around it and spoke softly. I leaned in close and listened. I never really got a good look at the guy’s face, but when he opened his hands, he was beautiful.

*

This is what it’s like: the shit comes on and you’re running up that ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night. The echo gets louder. More vivid. You can almost see the source through the upper atmosphere—it dances just ahead of you. Then, you’re stuck in a cloud and nothing makes sense. Pretty soon, you’re falling and the echo is fading until,

ca-chic-ca-chic-shhhhhh

ca-chic-ca-chic-shhhhhh

Over and over again.

*

New York pulled me back home. But it’s all the same no matter where I go. Each time, that runout groove comes a little quicker, hits a little harder. Twenty minutes, followed by that stutter, skip, pop, repeating endlessly until I pick up the needle and start the process over again. Even still. Records are miraculous things. For such small circles, they have an amazing capacity for emptiness.

*

I stand on the corner. I walk around. I wait for my man to come and I give him money.

He says, “Be careful with that.” He says, “Shit is strong.” He says, “Fire.”

I nod. I smile. I go to work and spend a lot of time in the bathroom.

I fall asleep at my desk.

I skip lunch.

I skip dinner.

I stand on the corner.

I turn thirty-four.

I turn thirty-five.

Thirty-six.

I turn thirty-seven, leaning on a wall, feeling like a tube of toothpaste with all the fresh squeezed out.

*

I’m shivering on the corner of Manhattan and Huron when my old roommate Don walks by, wearing a torn, striped T-shirt. Immune to the cold, he sports no jacket, carries no sweater. His platinum hair looks hacked off with a machete where it falls over his cloudy blue eyes.

He says, “Surprise, surprise.”

He says, “I’d ask how you’ve been, but.”

Snow is falling. I can’t stop sweating.

He says, “Been meaning to talk to you anyway.”

He says, “Since you stopped returning my calls.”

He says, “Thought I might find you here.”

My eyes are running. I can’t stop sniffling.

He says, “Look at this.”

He pulls a Polaroid out of his back pocket. The gesture contains all the sharp angles of his guitar playing. I sneeze into my sleeve, which leaves a spot of blood on the fabric. Don shows me the photo: a man with a microphone. Bright lights throw his shadow against the back wall of the stage.

Don says, “Look familiar?”

The street’s quiet. I check my phone. “You got an extra twenty bucks?”

He holds the photo up, “Just look.”

“Is that Sean?”

He says, “Sean’s been dead a long time. That’s you.”

“Looks just like Sean.”

He says, “Couldn’t stop what happened to him.”

He says, “I can’t stop what’s happening to you now.”

He says, “But I hope you’ll consider something. As a favor for me.”

He pulls a printout from his front pocket: Crossroads Mexico Ibogaine Clinic.

He says, “Experimental treatment.”

He says, “Famously unpleasant.”

I look down the street. I check my messages.

He says, “Can you hear me?” He folds the printout and says, “Go to Mexico. Get help.” He tucks the folded paper into the book I’m carrying: The Architecture of Happiness. I look over at the squat gas station on the corner and back at Don’s blank face.

“Did you have that cash?” I ask.

Don opens his wallet, hands me two ten-dollar bills.

My phone rings and everything starts sparkling, but it’s just my mom, so I hang up. Don takes the phone and types something into my contacts but then it rings for real and I run down the block without saying goodbye. I see my man and he takes my money and I go in the bathroom and then things finally sparkle for real.

__________________________________

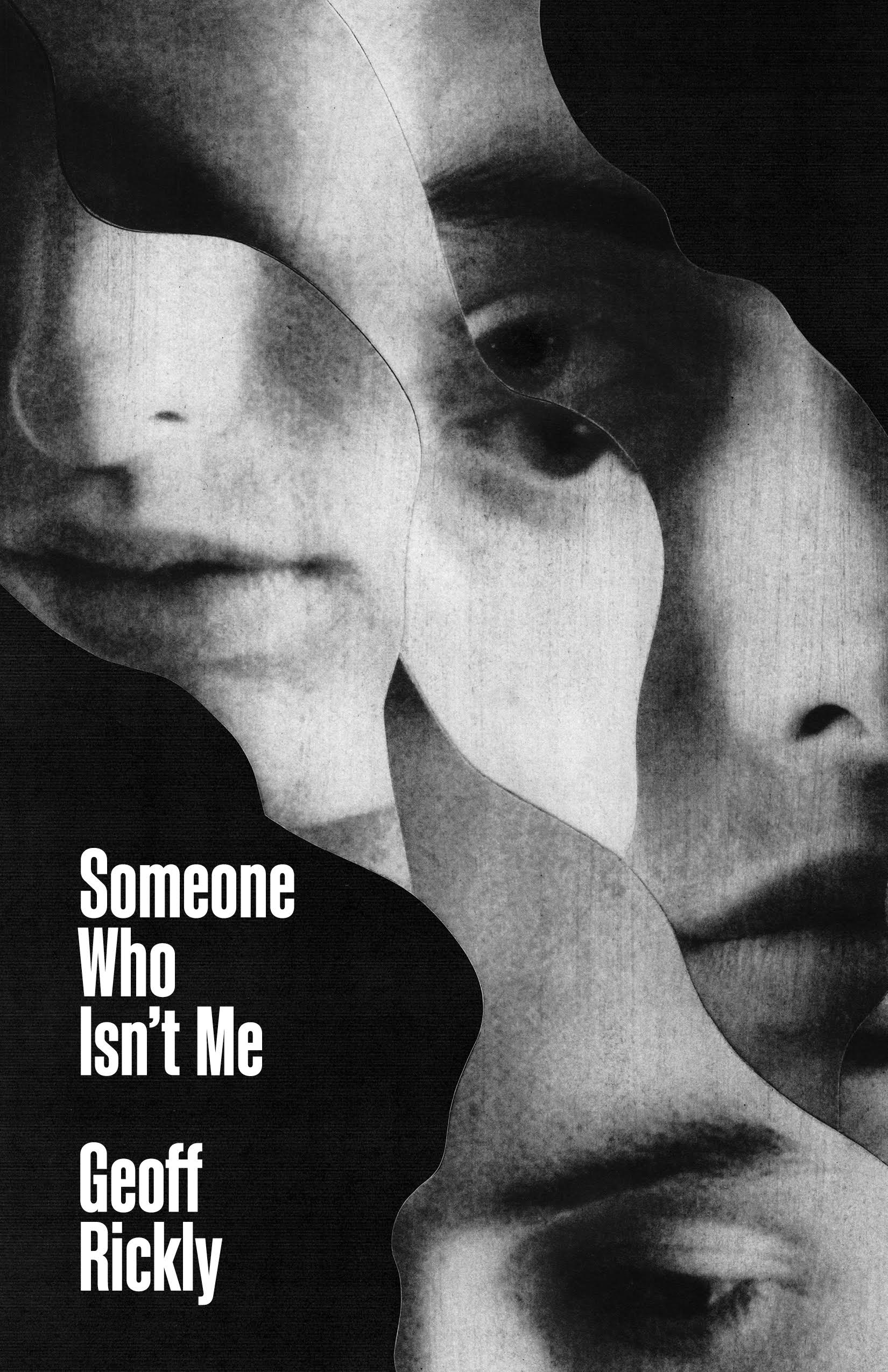

From Someone Who Isn’t Me by Geoff Rickly. Used with permission of the publisher, Rose Books. Copyright © 2023 by Geoff Rickly.