Solving the Mystery of My Father’s Journalistic Shorthand and Discovering… The Beatles?

Richard Sanger on the Surprises and Banalities Hidden in “Pitman” Notations

We thought we had heard his stories. My father is 92 and lives in a retirement home in a pleasant part of Ottawa. Originally English, Clyde spent his working life as a journalist in Britain, Africa, the US and Canada. Four years ago, when he and my mother began moving out of the big old house they’d lived in for close to 50 years, my three brothers and I helped clear things out. Paper in all its many forms was the house’s main ingredient: glossy government reports, dog-eared typescripts, ring-bound notebooks, fading blue aerogrammes, press releases from defunct NGOs and, of course, books of all kinds, hardbacks, paperbacks, novels, biographies, histories, atlases, dictionaries…

As the Manchester Guardian’s first-ever Africa and then UN correspondent in 1960s and later the Guardian and the Economist’s Canada correspondent, Clyde accumulated a lot of material; as an inveterate clipper and filer of stories, he had filing cabinets filled with articles on topics ranging from the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa to Saskatchewan’s potash industry. As a journalist herself, ardent Canadian and devourer of novels, my mother had certainly done her bit to fill the shelves—and then, at 86, had had the good sense to depart before we had to empty them.

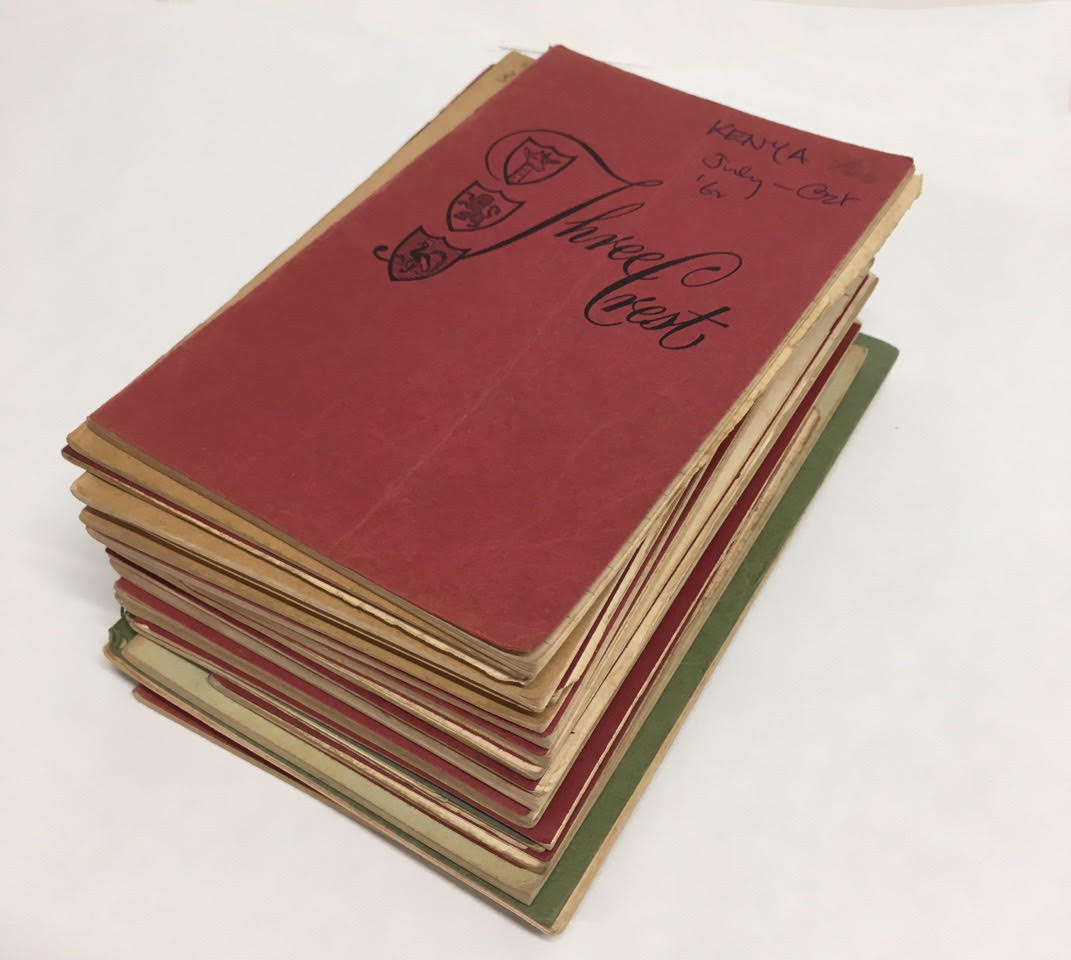

In this morass of print, perhaps the most intriguing items were a group of 50 or so small red notebooks filled with odd, runic squiggles occasionally interrupted by an English proper noun or a number. Looking at them, I could briefly imagine my father as a spy or cryptographer. In the early 1960s, well before cassette tape recorders, he had used these little Kenyan-made notebooks to record his notes in Pitman shorthand as he travelled through south, central and eastern Africa to report on the growing independence movements and interview nationalist leaders, colonial administrators, recalcitrant white settlers, tribal chiefs and such like.

Africa was where my parents had met and spent the first five years of their married life, the place they would hearken back to and remain involved with for the rest of their lives. There were often African students, journalists and politicians passing through our house and, as children, we were taught early about the injustices of apartheid and colonial rule. I remember vividly one of those African students at a Toronto party of my parents sneaking my seven- or eight-year-old brother and me out of the house in our pajamas to give us a ride in the dark on the motorcycle he had just bought—and then my mother appearing on the front steps to watch us return, with an expression—feigned or not—of mild concern.

When it came to finding a home for all this printed material, we quickly learnt our lesson: no one wants books these days. Not even the most obscure fugitive African-published progressive magazines from the 1960s that my father had saved were of interest to university libraries—let alone the actual works of Nyerere, Ngugi, Achebe, Lessing and others. And forget about the Encyclopaedia Britannica my father was given in partial payment for contributing the article on Zimbabwe. It turned out that a former colleague of Clyde’s had sold her Africa collection to Stanford University a few years previously and they had catalogued all those obscure magazines and publications from the 1960s. In contrast, there was a lot of interest in any original documents we might have from both Stanford and the Guardian Foundation’s new Guardian News and Media archive—and that meant those red notebooks full of Pitman shorthand. We chose the Guardian and duly shipped off five big boxes of notebooks and typescripts and letters to London.

People at the Guardian seemed genuinely excited about all those files and notebooks that had sat in my parents’ basement for close to five decades. In fact, when interviewed in the paper’s online edition about her job, the head archivist Philippa Mole had singled out Clyde’s papers as the kind of thing she found fascinating. They also ran a story about the donation—and seemed to think that the Pitman notebooks might include real surprises. I wasn’t so sure. Intriguing as it looked, it seemed to me you could just as easily use Pitman to record banalities as secrets. My guess was that there were probably quite a few interviews with obscure party officials in newly independent nations about their upcoming five-year agricultural plans. I obviously thought I knew his stories.

Then, last summer, two years after sending off the boxes, we got an email from Philippa saying that with some funding from the UK National Archives and the help of Britain’s University of the Third Age, the Guardian had found a group of some 40 Pitman-proficient volunteers who were going to transcribe the notebooks. They were all required to sign confidentiality agreements because it was thought the notebooks could contain sensitive material about living people. The four month project got underway just as the prospect of a Covid winter became reality and, partly because of my father’s idiosyncratic Pitman skills, served to bring an eclectic group of Englishwomen of a certain vintage together on line.

All women, yes: Pitman shorthand was widely taught in secretarial schools up until the 1970s (though the Moravian missionaries who developed the first written forms of Cree and Inuktitut in the 1860s also based their syllabic scripts on Pitman). Clyde, whose handwriting is distinctive and neat, writes a version of Pitman that looks like the marks an acrobatic worm might leave in the sand if attempting a straight A-to-B dash by a series of end-over-end leaps—one unpredictable squiggle after another. As one volunteer noted, he also tended to leave out vowels and periods and would often jump from one place and topic and date to another without any indication… All lapses that make sense if you realize he was only writing for one reader—himself.

Intriguing as it looked, it seemed to me you could just as easily use Pitman notebooks to record banalities as secrets.The volunteers set up an online forum where they would post and discuss difficult passages—and by and by seemed to bond with each other. A number had connections to Africa and so were especially interested in the material. One was an active Wikipedia contributor and so wrote up an entry for Clyde. Then a very thoughtful volunteer arranged for the group to write to Clyde and tell him of their experiences transcribing his notebooks. Many said they had enjoyed reviving their Pitman skills and that the challenge had helped them get through the enforced isolation of Covid. One volunteer who had lived in Uganda told of her delight in discovering that some of the words Clyde had written down in Pitman were Swahili. And another wrote how excited she was when she finally decoded the word “twiddling” as in what an interviewee was doing with a pencil.

But the biggest surprise came from Ann Brookfield who wrote “I enjoyed transcribing your conversations with the Beatles after their successful concert in the US.” What? We couldn’t believe it. Clyde had met the Beatles and never told us?! How often had we listened to the Beatles with him and he’d never said a word! How often had we heard about Jomo Kenyatta, Julius Nyerere, Joshua Nkomo and Ndabaningi Sithole… And not a peep about John, Paul, George and Ringo? My parents had had and played all the Beatles albums—there is no music I associate more with my early childhood. Think of how we could have impressed our classmates.

It took some probing from all four sons to get the full story. When my brother Matt asked why he had never told us, he said he just didn’t find them that interesting. When I asked, he said, with the inscrutable logic of a 92-year-old, well, it wasn’t a “very smart” place they had played in. We eventually learnt that, in August 1966, Clyde, the Guardian’s UN correspondent, was asked to sub for the paper’s holidaying Washington correspondent. My mother, now caring for four boys aged three to six without the help of our Kenyan nanny, was back in Canada with us. And then the Beatles came through town on their final tour ever.

Clyde went to the concert—in those days, they only played one 30 minute set—and then was apparently locked up with them and other journalists for a good deal longer afterwards until the police decided it was safe for them to leave the stadium. During this time, as Anne wrote, the Fab Four “resorted to entertaining you the journalists with their views on life, fame etc.” It’s not hard to conclude that Clyde, then 37, had been overexposed to these young musicians, all in still their early twenties but used to having the press find profundity in their every word.

The biggest surprise came from Ann Brookfield who wrote “I enjoyed transcribing your conversations with the Beatles after their successful concert in the US.”In the notebook entitled “Aug 66,” there are five pages of squiggles recording the encounter that begin simply with the initials “R P J G” and “P” (Paul) saying he would like to be reincarnated as a tree. The following pages do touch on some serious issues—the Vietnam war, the prospect of the band breaking up—but in each case the Beatles seem more interested in defusing controversy than creating it. In 1966, summer riots in Black neighborhoods were a regular feature of American life and the fact that this British band was now causing white youth to riot had driven conservatives and the Ku Klux Klan to hold rallies and make threats in response. In Memphis, someone threw a firecracker on stage. The young Liverpudlians were probably just hoping to get out of the US alive. Perhaps out of boredom with what they were saying, Clyde at one point reverts to his interest in his interviewee’s physical tics, noting that an unidentified Beatle “shreds a Kleenex like a fly whisk.”

But if the Beatles’ utterances seem pretty anodyne, Clyde’s Guardian story, published August 16, 1966, and unearthed online by my nephew Adam, sets the concert deftly in the context of American racial politics and answers all the difficult questions one might ask today. He notes that the Beatles’ audience was almost entirely white, but focuses on a riot that took place that same night in a Black neighborhood in Washington—and the fact that though “Negros” comprised the great majority of the city’s population, they had no say in its government. In short, there are riots and there are riots. Having come from Africa, where he’d watched a generation of young Black nationalists fight for and finally achieve independence, he clearly saw the continued oppression of African-Americans for what it was—and found Beatlemania pretty faddish and ephemeral by comparison. Though those Pitman notebooks did hide a surprise, it was one that in turn contained its own banalities.