So You've Decided to Write: Is Your Novel Actually Fiction or Non?

Truth Can Be Revealed in More Ways Than One

A young woman in a bar asked me if my novel, which she had heard about from the bartender, was fiction or nonfiction. The awesome post-literateness of her question was picked up by most of the fiction writers I worked with as evidence of the precariousness of their place in the culture, and they hurled it back and forth as a kind of crybaby mantra. I was editing Esquire and I told them there would always be a place for fiction in the magazine, but I wondered sometimes if I was lying.

Esquire was thought of as the most important cradle of New Journalism, if not the actual birthplace. Esquire ran the work of Tom Wolfe, Norman Mailer, and Gay Talese, among many others who unlocked the new form. Those writers have, of course, been claimed by every magazine that ever published their slightest ruminations, but while working primarily for Harold Hayes (at Esquire), Clay Felker (the Herald Tribune, Esquire, the Village Voice, New York) and Jann Wenner (Rolling Stone), they gave journalism a new position of importance above the short story—a status that lingers not as the 50-year literary hangover still talked about in MFA programs but as a paradigm shift.

Yet even as journalists were making their reputations by using the techniques of fiction, Esquire, Harper’s and the New Yorker were also publishing short stories by writers who were rooting their work in a grittier reality, even if that reality was imagined. Raymond Carver called it “a bringing of the news from one world to another.”

What was unfortunate during all of the ping-ponging of techniques between fiction and nonfiction is that very little attention was paid to the fiction side of the game and a most important idea was lost. The best fiction written since Esquire began, in 1933, had almost always answered the who, what, when, where and why questions associated with solid journalism but in ways that made it what John Updike called “the subtlest instrument for self-examination and self-display that mankind has invented yet.” Updike wrote this in his introduction to The Esquire Fiction Reader: Volume II (1986) and went on to explain that fiction “makes sociology look priggish, history problematical, the film media two-dimensional and the National Enquirer as silly as last week’s cereal box.”

How silly, then, not to recognize that questions of what is imagined and what is observed cannot be answered by simply asking what is true and what is not. This is what Tim O’Brien (Going After Cacciato and The Things They Carried) meant when he wrote about “story truth” being “truer sometimes than happening truth.” This is also what Ken Kesey meant when he would say that some things were “true even if they never really happened.”

The best writers can handle the truth either way. You can work on that…

That woman in the bar turned out to be plenty smart, and in another context—the one outlined above by Kesey and O’Brien—her question was a good one. And beyond the tricky jujitsu of journalistic ethics, it can be answered in one word: both. Or maybe with something about two plows in the same field.

I always paid much less for fiction, and when I went to novelists with an idea for a nonfiction piece, they were surprised by how much more the journalism paid—usually at least double. “What the fuck have I been doing?” is how Bill Kittredge put it when I called him in Missoula to talk him into what became a widely admired essay called “Redneck Secrets.” He had written mostly short fiction, which is what he taught at the University of Montana, but after that the personal essay was his favorite form.

If you were keeping score, like I had to be, it was the non-fiction that was pulling readers, but maybe the fiction writers were throwing the longest shadows. The best writers could handle the truth either way. I think this is because of a commitment to revealing the shadings and complexities of the human condition. This sounds ambitious and it is, weaving a safety net for the most difficult truths, catching them as they fall through our lives.

Head here to read more writing advice from Terry McDonell.

__________________________________

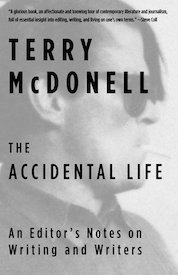

Adapted from The Accidental Life: An Editor’s Notes on Writing and Writers, by Terry McDonell (who is a cofounder of this website), published this month by Vintage. TerryMcDonell.com.

Terry McDonell

Terry McDonell has published widely as a journalist, top-edited a number of magazines, and was elected to the American Society of Magazine Editors Hall of Fame in 2012. He is the author of The Accidental Life: A Editor's Notes on Writing and Writers and Irma: The Education of a Mother’s Son. He is president emeritus of the Paris Review Foundation and co-founder of Literary Hub. TerryMcDonell.com