So Who Was Jack the Ripper?

Otto Penzler on the Most Famous Serial Killer of Them All

For a quick word game, give a person a subject and ask for the first name that comes to mind. There have been many great magicians, but ask any random person to name one and they’ll inevitably call up Houdini (and he was far from the most accomplished). Ask a casual baseball fan to quickly name any player of any era and he’ll say Babe Ruth (though he really was the greatest to ever play the game). Pick a soft drink, and they’ll say Coca Cola. How about a serial killer? Yes, it will certainly be Jack the Ripper.

While the world has had no shortage of murderers, with Cain wasting no time in getting humanity started on its blood-stained path, none has imposed himself on the public consciousness as indelibly as Jack the Ripper. Most experts, known in this very specific area of scholarship as Ripperologists, believe that the fiend committed his atrocities during a relatively short period of time in 1888, yet his sobriquet resonates throughout the world today.

It is reasonable to ask why this remains true after more than a century and a quarter. Certainly, there have been countless other killers whose names have screamed at us in headlines through the years, holding our attention for a while before fading and, mostly, disappearing.

There is a seemingly limitless number of people who have committed untold numbers of heinous acts throughout the long history of homo sapiens, a species almost unique in its ability to kill within the species for the sheer pleasure of it. With so many others having murdered in even greater numbers than Jack the Ripper, and some equally brutal (or worse, engaging in unspeakably depraved torture of living victims, a practice almost entirely eschewed by Saucy Jack), why does he continue to maintain his place at the top of the public’s consciousness?

While students of criminology are not unanimous in attributing the number of the Ripper’s victims, with five apparently accepted universally, but one, two, three, or four others also credited to him by various scholars, it is generally agreed that all the murders occurred during the autumn of 1888 (again, with outliers claiming at least an additional year at either end). The victims were all prostitutes in London’s East End, a ghetto teeming with the poorest segment of the population. The dark, narrow alleyways, often ending in cul-de-sacs, were perfect venues in which to commit an act of violence—or a transaction of a sexual nature, performed by a member of the largest profession of the neighborhood. The noxious fumes of coal stoves and fireplaces, as well as the factories located in the area, combined to provide an almost permanently darkened sky, a smog known as London particular. The women of the night, prowling the streets, looking for partners to pay them enough for a glass of warming gin, were perfect victims, willing—no, eager—to slip off to a darkened corner to quickly ply their trade. Although police patrolled regularly throughout the night, it was seldom by the cream of the force, and the odds of them catching a criminal in the act, with visibility frequently limited to two or three feet, were slim.

Since so few cared about the victims of the Ripper’s carnage while they were alive, why has their fate continued to resonate today? A likely reason is that he was never caught. Having spread a tsunami of terror for a short time, he disappeared completely, leaving his identity to be theorized, discussed, argued, and written about for decade after decade. It did not hurt his legacy of notoriety that he frequently taunted the police, with the complicity of the local press, by sending letters warning them of forthcoming attacks and daring them to catch him if they can.

The frisson of terror evoked by his name, Jack the Ripper—so much more chilling than merely Jack the Killer or Jack the Stabber—stays in the memory, and on the tongue, so easily. He was written about in such extreme terms, first of course in newspapers, but then in magazine articles and books, that he provided endless fodder for those who became intrigued by him. Theories about his identity were rampant, with clues clutched to advance one theory, while other possible pieces of evidence were ignored if they suggested that someone else was the genuine article. Other Ripperologists rushed to discredit the first theory and advance their own, which suffered the same fate at the hands of still other students of the crimes. Jack the Ripper has now been “proven” to be any one of at least a half-dozen people by various authors and scholars.

One of the first to be “identified” as Red Jack was known as Leather Apron for the garment he wore. He had evidently been seen becoming violent with a prostitute while drunk and was picked up by the police with several knives in his possession. When he explained that he repaired boots for a living, hence the leather apron and the knives, demonstrating how each was used in repairing footwear, the case against him weakened, and was finally destroyed when his family swore he was home with them every night that a murder had been committed.

The next suspect was more colorful. A mad Russian physician named Alexander Pedachenko was reportedly sent to England by the Czarist secret police to embarrass British detectives. In a variant theory, he had allegedly murdered several women in Russia in similar fashion to Jack’s but, because of his high social position, was sent to England instead of being arrested. Pedachenko was reported to be the Ripper in a manuscript written in French by Gregory Rasputin and found in his basement after the Mad Monk was assassinated in 1916. Skeptics pointed out that Rasputin’s house had no basement, nor did he read or write French.

One firmly held theory is that the culprit was another medical man, Dr. Stanley, who supposedly contracted syphilis from Mary Kelly (the last victim positively identified as having died at the hands of the Ripper) and, in a rage, began killing Kelly’s friends before slaughtering her. The weakness in that theory is that the very precise records of the General Medical Council of Great Britain do not show that anyone named Stanley practiced in London in 1888.

A newspaper reporter named Roslyn D’Onston, an alcoholic, drug abuser, advocate of black magic, and a friend of Aleister Crowley, was identified as Red Jack years after the fact when it was discovered that his stories included facts that only the Ripper would have known, but he was never charged and there are no records of his ever being interviewed, much less arrested.

Where do the theories end? They don’t. Arthur Conan Doyle was convinced that the fiend was really Jill the Ripper, probably a midwife who had been sent to prison for performing abortions and was a lunatic by the time she was released. Dr. William Gull, Queen Victoria’s physician, was named by a spiritualist. Gull admitted to having blackouts, unable to account for periods of time, but there was no physical evidence to suggest he had been in the East End at any time during the murders. These possibilities merely scratch the surface of the named suspects and those vaguely assumed to have committed the crime, from butchers to Jews to foreigners because, as several newspapers assured readers, no Englishman could have committed such atrocities.

Having now read more books, stories, articles, and reports about Jack the Ripper than I ever imagined I would, I confess that I have absolutely no idea who committed these heinous crimes. I’m not even sure how many victims there were, nor am I 100 percent convinced that there was a single murderer. I don’t know if he was brilliant enough to elude capture, night after night, or merely incredibly lucky. I don’t know if the police were competent, and I don’t know which of the thousands of newspaper accounts of the time were accurate. Amateurs have devoted years of studying and theorizing to arrive at a solution, and so have professionals; police officers, authors, scholars, historians, sociologists, and journalists have spent years on the subject, and they have no difficulty in sharing their opinions.

The only difference between them and me is that I admit I have no clue as to who Jack the Ripper was. It’s okay. I was only obsessed about it for a year—but I’ve recovered.

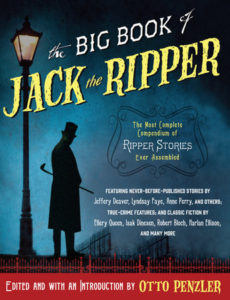

Adapted from the introduction of THE BIG BOOK OF JACK THE RIPPER, edited by Otto Penzler. Used with permission of Vintage Crime. Introduction copyright 2016 by Otto Penzler.

Otto Penzler

Otto Penzler is the founder of The Mysterious Press and The Mysterious Bookshop. He has written and edited several award-winning books and is regarded as the world's foremost authority on crime, mystery and suspense fiction.