“So Boundless an Affluence of Sublime Mountain Beauty...” When John Muir First Encountered Yosemite

Dean King on the Great American Wanderer’s Experience of the Sierra Nevadas

“I often wonder what man will do with the mountains—that is, with their utilizable, destructible garments. Will he cut down all the trees to make ships and houses? If so, what will be the final and far upshot? Will human destructions like those of Nature—fire and flood and avalanche—work out a higher good, a finer beauty? Will a better civilization come in accord with obvious nature, and all this wild beauty be set to human poetry and song? Another universal outpouring of lava or the coming of a glacial period could scarce wipe out the flowers and shrubs more efficiently than do the sheep. And what then is coming? What is the human part of the mountains’ destiny?”

–John Muir, August 1875

*

Most of the men who arrived in San Francisco during the 1849 Gold Rush, eager to get rich, stayed in town for only a few nights before pushing on to Oakland and the journey east toward the Sierra Nevada mines. And most soon learned that searching for gold was a largely futile and frequently treacherous pursuit in such a lawless land. While a few of the forty-niners would get rich, the majority came a long way only to find hardship and despair, as well as to see the city of their arrival burn to the ground seven times in eighteen months.

John Muir, who that same year had migrated with his father and several siblings (his mother and the rest would follow) from Scotland to southern Wisconsin, where they plowed the earth for crops, not gold, landed in San Francisco two decades later at the age of twenty-nine and did not give the place even a single night.

When the Muirs settled in Wisconsin, the country, under President James K. Polk, was just finishing up a massive expansion, adding California, the Oregon Territory, and Texas. Now the nation had just expanded again with the purchase of Alaska from the Russians for

$7.2 million. Muir seemed intent on exploring it all. Before reaching the West Coast, he had trekked through the Midwest and across the Deep South, finding ample opportunity to indulge his passion for nature, but it was California and Alaska that would ignite his soul, drive his intense curiosity, and compel him to fight to save nature from man.

Like San Francisco, Muir was well acquainted with fire—not to mention brimstone. While carving a farm out of the Wisconsin wilderness, his father, Daniel, had used bonfires to clear the land. One day while Muir stood before a fire so hot he could not approach it to toss on more branches, Daniel bade his son to study the flames: “Now, John, just think what an awful thing it’d be to be thrown into that fire,” he said, “and then think of hellfire, which is so many times hotter. Into that fire all bad boys, sinners of every sort who disobey God, will be cast just as we’re casting branches into this bonfire, and although suffering so much, their sufferings will never, never end because neither the fire nor the sinners can die.”

As a Disciples of Christ evangelist, Daniel believed in the literal truth of the Bible—the only book welcome in his house—and austere living. Muir learned his Bible verses at the threat of the whip, worked in the fields from dawn to dusk, and for a time, like the rest of the family, survived on gruel dished out once a day, thanks to his father’s interpretation of the “wholesome” and trendy Graham Diet, the brainchild of the evangelist Sylvester Graham, who believed that a sparse, meatless, and bland diet of whole grains, fruits, and vegetables would lower sexual desire and thus improve morality and health.

A series of clashes with his father propelled young Muir from the nest in 1860, at the age of twenty-two. By then he was a devout but restless spiritual seeker with a fierce independent streak.

Intensely smart and curious, the boy, who loathed bullies, caught glimpses of Wisconsin’s fleeting native peoples in the woods and felt the injustice of their being “robbed of their lands and pushed ruthlessly back. . . by alien races,” in a cruel case of “the rule of might with but little or no thought for the right or welfare of the other fellow if he were the weaker.” The teenager smuggled books of poetry and adventure into the house and read them in the wee hours of the morning, awakened when his early-rising machine—a clock-based invention that he had whittled out of wood—collapsed the foot of his bed and dumped him feetfirst into a pan of cold water.

A series of clashes with his father propelled young Muir from the nest in 1860, at the age of twenty-two. By then he was a devout but restless spiritual seeker with a fierce independent streak, a stout work ethic, a knack for innovation, a photographic recall of Scripture, and a wry sense of humor. His knowledge of Wisconsin’s plants and animals was encyclopedic, and his uncanny ability to endure peril and hardship, as well as to scamper over mountain terrain, would become legendary.

*

Fire played a role in the next chapter of Muir’s life too. During a furious blizzard, a freak gust of wind shot down the chimney and sucked smoldering embers up onto the roof of the factory deep in the Canadian woods where he and his younger brother Dan worked during the Civil War. Thirty thousand broom handles and six thousand rake handles went up in smoke. It was a crushing blow, as Muir had not only reengineered the factory, greatly improving its efficiency and profitability, but had also found a new family of sorts among its owners, who were devout and nature loving and who had offered him a partnership in the business.

The blaze cost Muir his savings and his hopes of returning to the University of Wisconsin, which he had attended for two years before running out of funds. In Madison he had met his soulmate and muse, Jeanne Carr, a botanist and the wife of Ezra Carr, a medical doctor and professor of natural sciences. Jeanne would serve as a mentor to Muir and introduce him to a number of the brilliant minds of their day, along with the woman who would become his wife.

Muir, sporting a neat beard and mustache below piercing gray-blue eyes, had been an outsize personality at Madison, where his room full of plant specimens and his mechanical clock-based inventions, including his early-rising machine and a hand-carved desk with a rotating book carousel, were a campus attraction. He had gained recognition for both his creative genius and his folksy vernacular. He was a shy but outspoken self-taught nature zealot with big hands powerful from farmwork and a penchant for moralizing.

Penniless after the fire, he took a job in a wagon factory in Indianapolis, where he invented a state-of-the-art process for making wagon wheels. But one day as he was repairing a machine belt, a wayward spike punctured his right eye and left him temporarily blind in both eyes due to a sympathetic reaction. Confined to a dark room, he lapsed into melancholy. “I have often in my heart wondered what God was training you for,” Carr wrote him while he was recuperating.

She had been amazed by Muir’s handmade inventions, his Scots-inflected poetic observations and insights, and his knowledge of and devotion to the natural world, and now she reassured her young friend with Emersonian verve: “He gave you the eye within the eye, to see in all natural objects the realized ideas of His mind. He gave you pure tastes, and the sturdy preference of whatsoever is most lovely and excellent. He has made you a more individualized existence than is common, and by your very nature, removed you from common temptations He will surely place you where your work is.”

While convalescing for a month, as his eyesight gradually recovered, Muir reflected on his purpose in life and decided to return to his most cherished pursuit—the study of nature. He resolved to travel to South America to follow in the footsteps of the German explorer and naturalist Alexander von Humboldt, whose writings about the interconnectedness of nature he admired.

He was mauled by mosquitoes, chased by an alligator, and suffered the fever spasms of malaria. By the end, in Cuba, he was delirious from hunger and disease.

In the fall of 1867, Muir took a train from Indianapolis to Jeffersonville, Kentucky, then set out on foot through the Southern wilderness to the Gulf Coast of Florida, carrying little more in his rubber travel bag than a change of undergarments, his plant press, and copies of the New Testament, Paradise Lost, and Robert Burns’s Poems. In the course of a thousand miles, he met people even more isolated from the rest of the nation than he and his siblings had been on their remote Wisconsin farm and narrowly escaped a confrontation with a band of ex-Confederate marauders.

He was mauled by mosquitoes, chased by an alligator, and suffered the fever spasms of malaria. By the end, in Cuba, he was delirious from hunger and disease, but his walk in the wilderness had provided some clarity. He had seen life rugged and raw, nature broad and powerful. He had been reduced, stripped bare, and separated from a world ruled by the desire for material success.

Haunted by malarial fevers, Muir postponed retracing Humboldt’s route. He decided instead to pursue nature in the American West and booked passage from New York to California, via the Isthmus of Panama. By the time he had disembarked from the steamship Nebraska in San Francisco, in March 1868, he was already eager to escape the brawl of humanity—the whiskey, gambling, and prostitution dens of the city’s notorious Barbary Coast—and to head for the vast forests, mountains, and wilderness that he had heard so much about.

He stopped a man on the street carrying a carpenter’s kit on his shoulders and asked him for “the nearest way out of town to the wild part of the State.” Surprised, the man set down his kit and inquired, “Where do you wish to go?” “Anywhere that’s wild,” Muir responded. He and another passenger from the voyage, Joseph Chilwell, a world-wandering cockney, who called Muir “Scottie,” took the ferry to Oakland, as directed, and set out for Yosemite Valley, not by the usual route—a river steamer to the town of Stockton and then on by stage and horseback—but on foot, “drifting leisurely,” as Muir proposed, paying little heed to roads or time and camping in their blankets wherever nightfall overtook them.

Muir was soon smitten by California’s sun-drenched lowlands and coastal ranges, where larks sang amid hills so blanketed with flowers “they seemed to be painted.” Happy and relaxed, he wanted only to take his time crossing the 250 miles to Yosemite in the Sierra Nevada. “Cattle and cultivation were making few scars as yet,” he later wrote, “and I wandered enchanted in long, wavering curves, aware now and then that Yosemite lay to the eastward, and that some time, I should find it.”

Surviving on tea and unleavened flour cakes toasted on coals—though he had been a crack shot as a youth, Muir had given up hunting—the pair followed a rough wagon road, shunning lodging of any sort.

Muir and Chilwell walked down the Santa Clara Valley, and on a bright morning at the head of the remote fourteen-mile Pacheco Pass through the Diablo Mountains of the Coast Ranges—a place once known as Robber’s Pass—Muir was stunned by his first view of the Sierra. In the foreground, at his feet, lay the San Joaquin and Sacramento Valleys, “the great central plain of California, level as a lake thirty or forty miles wide, four hundred long, one rich furred bed of golden Compositae,” some of them taller than he was, a floral landscape that he called “the most divinely beautiful and sublime I have ever beheld.”

In the distance, on the eastern edge of this “lake of gold,” the “mighty” Sierra rose “in massive, tranquil grandeur”:

. . . so gloriously colored and so radiant that it seemed not clothed with light, but wholly composed of it, like the wall of some celestial city. Along the top . . . was a rich pearl-gray belt of snow; then a belt of blue and dark purple, marking the extension of the forests; and stretching along the base of the range a broad belt of rose-purple, where lay the miners’ gold and the open foothill gardens—all the colors smoothly blending, making a wall of light clear as crystal and ineffably fine, yet firm as adamant. Then it seemed to me the Sierra should be called, not the Nevada or Snowy Range, but the Range of Light.

Muir had not come to the Gold Rush hills looking for gold, but he had found it anyway. “It was all one sea of golden and purple bloom, so deep and dense that in walking through it you would press more than a hundred flowers at every stop,” he recounted. At sunset each day, he and Chilwell threw down their blankets “and the flowers closed over me as if I had sunk beneath the waters of a lake.” When he opened his eyes in the morning, his gaze fell on plants he had never before encountered, and his botanical studies began before he got up. “Not even in Florida or Cuba had I seen anything half so glorious,” he said.

Change was about to come fast to Central California amid rampant farm expansion and the consequent water wars. “I have always thanked the Lord that I came here before the dust and smoke of civilization had dimmed the sky and before the wild bloom had vanished from the plain,” he would tell an audience almost three decades later. But in that moment, he and Chilwell felt enthralled and awakened by the fresh and varied scents in the air—the sweetest air there is to breathe, Muir hailed it.

“The atmosphere was spicy and exhilarating,” he recalled. “This San Jose sky was not simply pure and bright, and mixed with plenty of well-tempered sunshine, but it possessed a positive flavor, a taste that thrilled throughout every tissue of the body.” Muir and Chilwell, having lived only on “common air” all their lives, now discovered “multitudes of palates” and a much vaster “capacity for happiness” than they knew existed. “We were . . . born again; and truly not until this time were we fairly conscious that we were born at all,” Muir enthused. “Never more, thought I as we strode forward at faster speed, never more shall I sentimentalize about getting free from the flesh, for it is steeped like a sponge in immortal pleasure.”

They crossed the San Joaquin River at Hill’s Ferry, then headed east along the Merced River toward Yosemite Valley, a former Ahwahnechee stronghold and sanctuary. After ascending the foothills from Snelling Ranch, the Merced County seat, which simplified its named to Snelling two years later, to the gold mining town of Coulterville, nearly fifteen hundred feet higher in elevation, they bought supplies—flour, tea, and a shotgun—and asked the Italian storekeeper about the route into the valley. He described forests of pines up to ten feet in diameter but warned that it had been a severe winter and the Yosemite Trail was still buried in snow up to ten feet deep. He advised them to wait a month to avoid getting lost in the snowdrifts. “It would be delightful to see snow ten feet deep and trees ten feet thick, even if lost,” Muir replied, “but I never get lost in wild woods.”

Surviving on tea and unleavened flour cakes toasted on coals—though he had been a crack shot as a youth, Muir had given up hunting—the pair followed a rough wagon road, shunning lodging of any sort. The road ended at a trail that climbed up the side of a ridge dividing the Merced and the Tuolumne to Crane Flat, at six thousand feet. Here they found the promised great pines, towering firs, and six feet of snow.

Muir considered it “a fine change from the burning foothills and plains.” Coming to an abandoned cabin, they decided against wading on through the snow. Although Muir preferred to sleep under the stars, regardless of the snow, Chilwell, who was eager for even a semblance of a roof overhead, swept away the snow on the cabin floor and made a bed out of silver-fir boughs. He had asked Muir to teach him how to shoot and had pinned a target to the outside of the cabin for Muir to test the gun.

As Muir prepared to shoot at it from thirty yards away, Chilwell disappeared. Muir, unaware that he had gone back inside the cabin, fired, and Chilwell came running out, hollering, “You’ve shot me! You’ve shot me, Scottie!” The lead shot had penetrated the soft pine wall and Chilwell’s several layers of clothing and embedded in his shoulder. Muir had to pick out the pellets with a penknife. They set out again the following day through the snow, Muir guiding them by the topography.

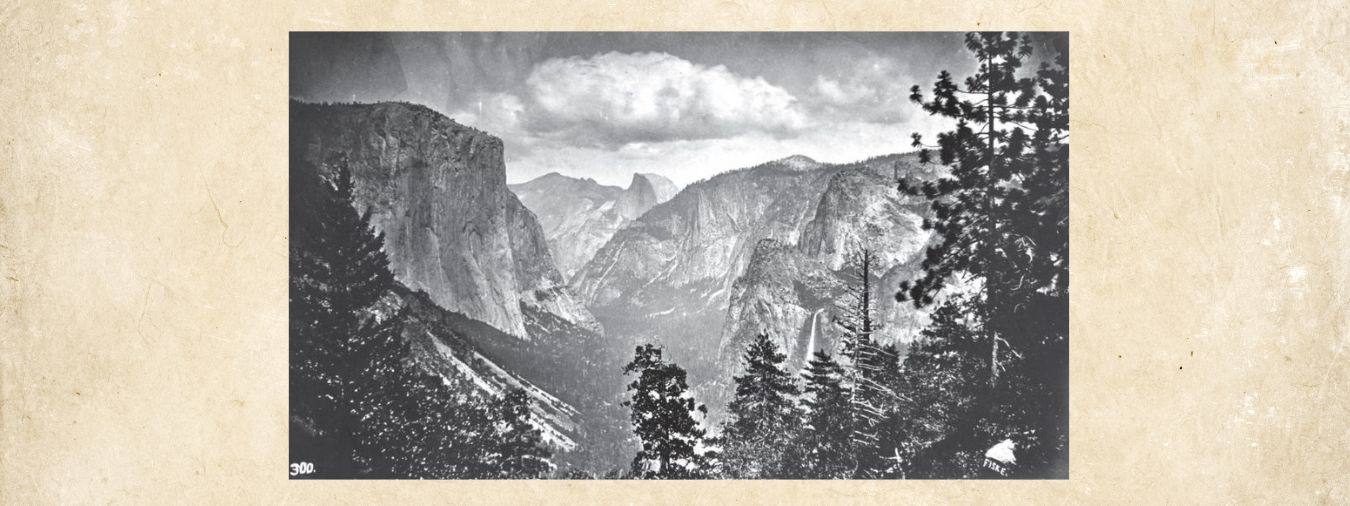

Just as they reached a trail on the Yosemite Valley rim, Bridalveil Fall came into sight. “See that dainty little fall over there, Joe?” Muir said. “I should like to camp at the foot of it to see the ferns and lilies that may be there. It looks small from here, only about fifteen or twenty feet, but it may be sixty or seventy.” Later, after observing the six-hundred-foot fall up close, he laughed. “So little did we then know of Yosemite magnitudes!”

As they camped in the Bridalveil Meadow, a grizzly bear approached to within thirty feet, though on the other side of their fire. Muir added buckshot to the bird shot in the gun and waited silently, hoping the bear would not come closer, as Chilwell trembled beside him. Fortunately, the grizzly finally ambled off.

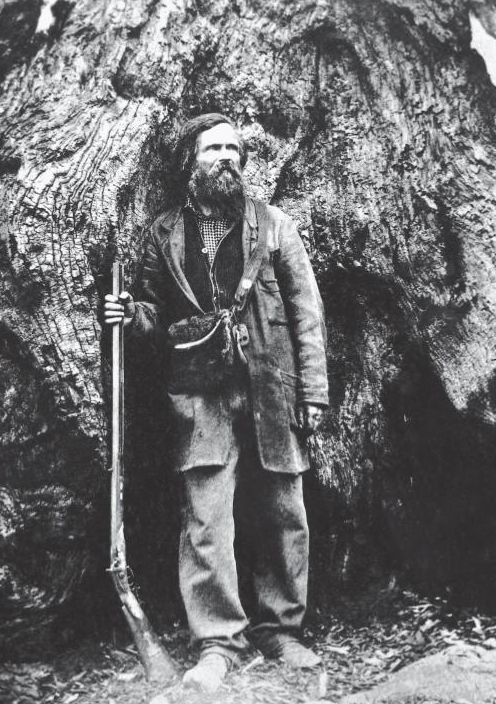

For ten days the two explored the falls and the views from the valley walls, sketching and collecting ferns and flowers. Muir had seen enough to know he had to return. In the meantime, although low on provisions, the pair headed down the south fork of the Merced River to see the famous trees. After a few days, they reached Wawona—“big tree” in the Miwuk language, derived from the sound of the hoot of an owl, the guardian spirit of the sequoias—and the nearby Mariposa sequoia grove. Here they met a woodsman who more than a dozen years earlier had built his cabin at a river ford near the trail that led to the sequoia grove and to the valley.

Galen Clark, a Canadian-born former gold miner, who had been made the Guardian of the Valley by the park commissioners in May 1866, gave them a supply of flour and fresh meat. They reached the grove after dark, built a great fire from the fallen brush buried beneath the snow, and roasted the meat, neither having ever tasted bear before. Chilwell, famished, gobbled his down (he would later also eat owl soup), but Muir, as deprived as he was, found the pungent, oily meat inedible. He would prove on this and many occasions to have an unusual ability to thrive on the most minimal intake. Camping in the Mariposa Grove, amid “the greatest of trees, the greatest of living things,” was nourishment enough for him.

Galen Clark in front of the Grizzly Giant in Mariposa Grove. Carleton Watkins, ca. 1858-60.

Galen Clark in front of the Grizzly Giant in Mariposa Grove. Carleton Watkins, ca. 1858-60.

Little could Muir know that he and Clark would eventually spend much time together. Four years after this first meeting, in 1872, Clark would assist Muir in setting stakes in a Mount Maclure glacier as Muir tested his hypothesis that glacier motion shaped Yosemite Valley and all the Sierra Nevada. They were two of a kind.

“I’ve tried many kinds of work,” the shepherd wasted no time in informing him, “but this of chasing a band of starving sheep is the worst of all.”

Muir, known for his swift pace over steep and rough terrain and his unconcern for hardship, admired Clark’s ease in passing through the dense chaparral and his ability to sleep “anywhere on any ground, rough or smooth, without taking pains even to remove cobbles or sharp-angled rocks.” These two single-minded men would later find themselves essential companions in the fight to save Yosemite.

After their adventure Muir and Chilwell headed west to Snelling Ranch, on the San Joaquin plain, and took jobs as hired hands on a farm. While Muir had found farming under his father grim and debasing at times, he now discovered a renewed appreciation for agricultural pursuits and decided to stay on after Chilwell left and help the other hands—a mixture of Spaniards, Britons, and Native Americans—harvest wheat, shear sheep, and break Arabian mustangs.

As the summer of 1868 gave way to fall, he abandoned his idea of traveling in the footsteps of Humboldt to stay in California for another year, or perhaps two. The beauty of the Sierra Nevada had surpassed his expectations, and he wanted to explore it.

In the spring, he found an undulating flower-filled depression between the Merced and Tuolumne Rivers, which he dubbed Twenty Hill Hollow. He calculated that every square yard of the hollow held from a thousand to ten thousand flowers. “The earth has indeed become a sky,” he enthused, “and the two cloudless skies, raying toward each other flower-beams and sun-beams, are fused and congolded into one glowing heaven.”

From one of the surrounding hills, he could see Mount Diablo and Pacheco Peak, far away but not distant. “Their spiritual power and the goodness of the sky make them near, as a circle of friends,” he wrote. “Plain, sky, and mountains ray beauty, as if warming at a camp-fire. Presently you lose consciousness of your own separate existence; you blend with the landscape, and become part and parcel of nature.”

Before long, an Irish sheepherder named John Connel, who liked the inquisitive, poetic, hardworking Wisconsin Scot, approached Muir and asked him to watch his flock. Once a shepherd with only a couple dozen scruffy ewes, Connel, who went by the name Smoky Jack, was a well-known success story, now “sheep rich,” with a flock of thousands in three bands. Smoky Jack offered Muir $30 a month plus room and board and assured him the sheep would show him the range and “all would go smooth and aisy.” For that lie, Muir would skewer Smoky Jack with a Twain-worthy humorous description:

[Smoky Jack] lived mostly on beans. In the morning after his bean breakfast he filled his pockets from the pot with dripping beans for luncheon, which he ate in handfuls as he followed the flock. His overalls and boots soon, of course, became thoroughly saturated, and instead of wearing thin, wore thicker and stouter, and by sitting down to rest from time to time, parts of all the vegetation, leaves, petals, etc., were embedded in them, together with wool fibres, butterfly wings, mica crystals, fragments of nearly everything that part of the world contained—rubbed in, embedded and coarsely stratified, so that these wonderful garments grew to have a rich geological and biological significance.

All Muir had to do was find his way to the shepherd’s cabin, about five miles away on Dry Creek. “You’d better go right over tonight, for the man that is there wants to quit,” Smoky Jack said. “You’ll have no trouble in finding the way. Just take the Snelling road, and the first shanty you see on a hill to the right—that’s the place.”

As Old World traditions and British Romantic poetry still colored Muir’s notion of shepherding, Smoky Jack’s offer seemed to provide an ideal opportunity to observe and explore nature on the wild hillsides. Although Muir had grown up around beasts of all sorts, he had no idea what he was getting into. He arrived at the Dry Creek cabin at dusk the next day to find Smoky Jack’s young shepherd fixing his supper. A quick look around the defiled place hinted at a long, slow descent to its hellish state.

“I’ve tried many kinds of work,” the shepherd wasted no time in informing him, “but this of chasing a band of starving sheep is the worst of all.” He then launched into a recitation of his grievances and admonitions, liberally cursing sheep in general and this flock in particular, while preparing to depart. Taken aback, Muir begged the brusque shepherd to stay the night and show him the ropes in the morning.

“Oh, no need for that!” the shepherd chided. “It’d do you no good. I’m going away tonight. All you have to do is open the corral in the morning and run after them like a coyote all day and try to keep in sight of them. They’ll soon show you the range.” With that, he departed, leaving Muir to explore his new home for himself. A closer look did not reassure.

Muir saw how the shepherds preceding him had had their spirits crushed, living like hapless beasts themselves. He seethed at the greed and cruelty of California’s industrial sheep farming.

The layers of filth and detritus showed that previous shepherds had left the place in shambles and the most recent had merely augmented it. Among the Boschian heaps of ashes, rancid old shoes, and other rubbish strewn around the dirt floor were sheep jaws and skulls, some with ram horns, skeletons with attached tendons, and “other dead evils.” Though pervious to rain, wind, and light, the hut reeked of charred grease, mold, and sweat. It took little imagination to picture small demons dancing here with fiendish glee.

Inclined to sleep outside under the stars, Muir discovered that, despite the two sheepdogs he had inherited, aggressive wild hogs rooted and ruled at night. He opted for the rickety bed-shelf in the corner of the shack, its mattress a wool sack stuffed with straw and old overalls, and gazed at the stars through the gaps in the roof while drifting off.

It was a cloudless morning, and when he opened the corral gate, eighteen hundred sheep burst out, “like water escaping from a broken flume,” as he put it, trampling through Dry Creek and scattering across a dozen hills and rocky banks. He went in pursuit, not quite sure what to do and feeling “that like spilt water they would hardly be gathered into one flock again.” While the old and lean soon tuckered out, a thousand or so pushed on until they at last homed in on their own suitable grazing patch.

But five hundred or thereabouts, whom Muir dubbed “secessionists,” bolted off, halting only occasionally to pluck green shoots, seemingly more interested in escape and adventure or quite possibly in testing and hazing their new sitter. Muir dashed ahead to try to cut them off, and they soon discovered that he was even more fleet-footed and stubborn than they were. With the hot afternoon helping to tire out the runners, he slowly managed to turn them back toward the herd and create a semblance of order. About two hours before sunset, he started driving the flock the two miles back to the corral. They reached Dry Creek at dusk, where to his surprise his charges obediently formed parallel columns and streamed back into the pen.

It turned out to be an unusually bitter winter. Through the solitary months, Muir came to understand the previous shepherd’s desperate need to leave the place. With California’s free pasturage and favorable climate, sheep owners might double their wealth every other year, but while the owners got rich, their shepherds toiled away in harsh isolation and rarely managed to become owners themselves.

In Scotland, a shepherd usually came from a line of shepherds, inheriting a love and aptitude for the life. He had only a small flock to tend, supported by his collies, saw family and neighbors regularly, and often had time to read books in the field and thus “to converse with kings.” But the California shepherd, alone in his dingy hovel, stupidly weary, had no balance in his life, leading to dejection, poor health, and in a few cases even insanity.

For five months Muir observed the life cycle of sheep with all its complications and pleasures. He participated in the arrival and departure of life over and again. Hundreds of ewes lambed that spring, only for the newborns to be exposed to the unseasonably frigid weather. He carried many of them into the hut to keep them warm by the fire and bottle-fed more than two hundred. But he could not protect the entire flock, and one icy morning he woke to find that about a hundred sheep, huddled together against the cold, had frozen to death overnight.

One day out on the open plain, he discovered two little black piglets, “lying dead in a small bed which they had dug in the sand just the length of their bodies. They had died without a struggle side by side in the same position. Poor unfriended creatures.” And it dawned on him: “Man has injured every animal he has touched.”

Indeed, Muir had recently been wrestling with the hypocrisy of “civilized man,” as he recorded in his journal, in no uncertain terms, while walking across the South:

Let a Christian hunter go to the Lord’s woods and kill his well-kept beasts, or wild Indians, and it is well; but let an enterprising specimen of these proper, predestined victims go to houses and fields and kill the most worthless person of the vertical godlike killers,—oh! that is horribly unorthodox, and on the part of the Indians atrocious murder! Well, I have precious little sympathy for the selfish propriety of civilized man.

Muir saw how the shepherds preceding him had had their spirits crushed, living like hapless beasts themselves. He seethed at the greed and cruelty of California’s industrial sheep farming, where as long as resources were unlimited and cheap, animal life was taken for granted. Despite the hardships, Muir later valued his time tending Smoky Jack’s flock, some of the most trying work he ever did.

Yosemite, First Blush, Summer 1869

At the beginning of June, after seeing some of Muir’s sketches and hearing that he wanted to study the higher regions of the Sierra, Smoky Jack’s neighbor Pat Delaney offered him a job overseeing his shepherd. Delaney, whom Muir described as “bony and tall, with a sharply hacked profile like Don Quixote,” assured Muir that his main duty would be to keep an eye on the shepherd, Billy Simms, who would do the actual herding, and that Muir would be otherwise free to collect plants, sketch, explore, and observe the wildlife.

Delaney, or “the Don,” as Muir called him, said he would travel with them to the first mountain camp and then periodically return with mail and provisions as they moved higher up the mountains. Muir would only be needed in case of accidents or other emergencies. Eager to return to the highlands, he agreed.

He would not be alone this time. The traveling party included a Chinese workman, a Native American herder, and a new companion: Carlo, a Saint Bernard whose owner had asked Muir to take him along for fear that the valley’s summer heat might be too much for the shaggy creature. As the group began the climb, Muir gazed at the snowy peaks above them and prayed that he would get to explore them.

Delaney and the others left Muir and Simms, the shepherd, in a place that could not have been more unlike Smoky Jack’s hut. Muir found enchantment and peace in the camp grove. He was now acquainted with the art of tending sheep, and Simms, an experienced hand, was responsible for them, allowing Muir to explore the wilderness, making keen observations on ferns, black ants, and sugar pines. “Life seems neither long nor short,” he observed, “and we take no more heed to save time or make haste than do the trees and stars. This is true freedom, a good practical sort of immortality.”

One morning while Muir was absorbed in his journal, he looked up and was surprised to see a Miwuk man only steps away. The moment resonated with Muir. “All Indians seem to have learned this wonderful way of walking unseen,” he would write. He thought this skill had probably been acquired over generations of hunting and fighting and survival against enemies.

“This June seems the greatest of all the months of my life,” Muir wrote in his journal, “the most truly divinely free, boundless like eternity, immortal.”

Muir admired how Native Americans had long lived in harmony with nature. “Indians walk softly and hurt the landscape hardly more than the birds and squirrels,” he wrote. Their trails were barely noticeable and their brush and bark huts ephemeral. Their most lasting impact was caused by the fires they made in the forests to improve their hunting grounds. In contrast, white men blasted roads in the solid rock, dammed and tamed wild streams, and washed away hills and the “skin of the mountain face” while searching for gold. Even worse, the white man had debased the Native Americans, until they were no more harmonious with nature than he was.

“This June seems the greatest of all the months of my life,” Muir wrote in his journal, “the most truly divinely free, boundless like eternity, immortal.” But in early July his and Simms’s rations dwindled until the only thing they had to eat was mutton, which was soon almost inedible to Muir. They began to feel weak and lethargic. Muir’s stomach ached to a degree he found difficult to bear.

“We dream of bread, a sure sign we need it,” he wrote. “Like the Indians, we ought to know how to get the starch out of fern and saxifrage stalks, lily bulbs, pine bark, etc.” He admired their ability to live off the land on berries, roots, birds’ eggs, bee larvae, and ants. “Our education has been sadly neglected for many generations.”

Finally, Delaney returned with fresh supplies, and Muir and Simms quickly recovered. It was time to move the sheep higher into the mountains, and while they did, Muir noted that the Native American who worked for Delaney was calm and alert and “silently watched for wanderers likely to be overlooked.” At night he needed neither fire nor blanket to stay warm. “A fine thing,” thought Muir, who would push the bounds of wilderness survival, always striving to do more and stay longer with less, “to be independent of clothing where it is so hard to carry.”

On July 11, they camped at seven thousand feet beside ice-cold Tamarack Creek, which flowed swiftly through a high green meadow. Only a few hundred yards below them, the ground was rocky with sporadic stunted trees growing from seams and fissures. Here and there were massive boulders that had somehow traveled from afar—as their color and composition showed—and been left in this spot eons ago. Muir wondered how they had gotten here. He examined them closely and found the answer written on the stone itself. The most resistant and unweathered surfaces showed parallel scoring and striation, suggesting that the region had been swept by a glacier, grinding down the mountains, wrenching and scraping and carrying great fragments of the landscape with it. When the ice melted, it deposited the boulders where Muir now found them.

With Chilwell, Muir had only whetted his appetite for Yosemite Valley, a place of enchantment considered sacred by the now displaced Ahwahnechee, and he was eager to experience it more deeply. He was granted his wish after only a few days, when snow in the high mountains forced Simms to move the flock to lower elevations. As they approached the great valley—which had in the two decades since its “discovery” and the brutal expulsion of the Ahwahnechee achieved an almost mythical status across the nation—a party of tourists passed nearby on horses. They seemed to care little for the scenery, and Muir felt no need to talk to them. Though he had many close friends, male and female, he missed society little and looked forward to studying and sketching the plants and rocks in solitude and to scrambling with Carlo along the spectacular valley rim.

As they pushed east over the rim into the Yosemite Creek basin, Muir marveled at the clear evidence of the former presence of ice in the glacier-polished granite. “How raw and young this region appears!” he wrote. “Had the ice sheet that swept over it vanished but yesterday, its traces . . . could hardly be more distinct than they are now.” Horses, sheep, and men all slipped on the smooth stone.

They reached Yosemite Creek about two miles before it plummeted into the valley. Delaney and Simms and their helpers plunged into a slippery battle with the flock, which was determined not to cross the swift forty-foot-wide and four-foot-deep creek and responded like a force of nature. As each group was pushed into the stream, it returned at its soonest opportunity to the flock waiting on the creek bank. In vain Delaney heaved sheep after sheep into the current and even leaped in himself to lead a surge. The effort was not won until it was abandoned.

Before him he saw the grandeur that the nation, so recently smothered in its horrible bloodshed, possessed. The heights to which it could soar. He saw redemption.

The famished sheep then suddenly decided on their own to cross the stream and search for new forage, and their scramble to get to the other side created a new crisis. “The Don jumped into the thickest of the gasping, gurgling, drowning mass,” Muir reported, “and shoved them right and left as if each sheep was a piece of floating timber.” Although Muir “expected that hundreds would gain the romantic fate of being swept into Yosemite over the highest waterfall in the world,” none did, and all were soon happily munching and baaing on the far bank, as if this tumultuous minor miracle—their safe crossing—had never happened. “A sheep can hardly be called an animal,” he concluded, with rare disdain for the natural world. “An entire flock is required to make one foolish individual.”

The next day Muir set out on his own with Carlo, climbing a fragrant steeply rising slope on the valley’s east rim. Before they reached the top, they veered south into a shallow basin, and Muir set up a bivouac. After lunch, they explored Indian Canyon’s western ridge and, as they gained the top, looked out on a stunning panorama of the upper basin of the Merced River—the mountains above Yosemite Valley—snowcapped peaks kissing a cobalt sky above domes, canyons, and upsweeping dark forests, windless and still, all radiant with sunshine. Overwhelmed by “so boundless an affluence of sublime mountain beauty,” the likes of which he had never before seen, Muir felt himself swell with spirituality and joy. A spontaneous shout escaped his lips, and his core and limbs shook “in a wild burst of ecstasy.”

He took several strides but was brought up short, as a massive grizzly rose from its hiding place. The bear shook free of a thicket of brush, sucked in wind, and roared off, trampling the twisted manzanita bushes in its desire, Muir imagined, to escape the human lunatic. Carlo, his ears pinned back in fear, shook feverishly, waiting for the command to hunt. The glorious sight below him was what Muir had wandered so far—the distance hardly seemed possible—to discover. He was like a drop of blood propelled unwittingly through the circulatory system of the war-ravaged country to its very heart chamber: the valley of Yosemite.

Before him he saw the grandeur that the nation, so recently smothered in its horrible bloodshed, possessed. The heights to which it could soar. He saw redemption. This was the place where his enthrallment with nature, which had caused him to spurn all reasonable and worldly pursuits—his belief in its worth, power, and sacredness—would crystallize. He felt the warmth of his friend Jeanne Carr’s approving gaze, and a yearning for her presence.

Under this spell, with Carlo at his heels, Muir followed the ridge as it gradually fell to the south, and between Indian Canyon and Yosemite Falls, they made their way to the cliff’s edge. Here, again, the view brought him up. They were on top of the world. The entire valley stretched out before them, and below, the majestic river of mercy, the Merced, sparkled as it swept through an Eden of sunlit meadows and oak and pine groves. At the upper end of the valley, Tissiack, or Half Dome (also known as South Dome), presided over this landscape, thrusting nearly a mile into the sky, so well proportioned that it drew the eye like a magnet away from the beauty around it, absorbing and magnifying the falls, the meadows, the cliffs, and the distant mountains.

Eager to see the long view right down to the valley floor, Muir jogged along the rim, but its sloping edge made it difficult to find a vantage point. He searched for a slot or a sheer ledge. When he finally found a jutting shelf, he shuffled to the very edge, set his feet, braced his legs, drew his body up tall, and craned into the air. Muir had no fear of heights, perhaps dangerously, and after four years on the move, roved over the terrain like a billy goat, trusting his legs absolutely.

For a moment, though the rock was solid, the notion of its breaking off and sending him on a half-mile plummet gave him a frisson. But the feeling soon passed, and his nerves grew steady again. Over the next hour, in the grasp of something more powerful than his own will, he took yet more risks to see this spellbinding view, each time swearing not to venture so close to the edge again.

Eventually, he and Carlo arrived at the now-narrow Yosemite Creek rushing over twinkling granite on its way to the precipice. Just before the drop, it gathered in a basin and relaxed, the boil of the rapids calmed, the water a somber gray. Then it slowly glided over the lip of the pool, onto the last slope, accelerating swiftly to the brink. Finally, with—as Muir saw it—“sublime, fateful confidence,” it flew into the air, where it levitated momentarily, as if resisting gravity, before it escaped to another world. In its departure from the raw mountaintop to the green valley, it burst into particles, and a shimmering rainbow—a spray bow—marked this transformation from caterpillar to butterfly.

Wishing to be part of this God-work as nearly as possible, Muir took off his shoes and stockings and, pressing his feet and hands against the slick granite, worked his way down until his head was near the booming, rushing, energizing stream. Noticing that it leveled before its dive, he hoped he could lean out over the edge and see down into the falling water and through it to the bottom. But when he reached the edge, he discovered it to be false. Another, steeper, ledge lay below. It appeared too steep to allow him to reach the brink.

However, once again, he could not convince himself to abandon the effort. He could see the cliff fully now and spied a narrow rim, just wide enough to hold his heels. Studying the polished surface of river wall, he noticed a rough seam on the steep rock face, a fault line that might provide him the needed fingerholds to reach the cliff’s edge. His nerves tingled as he considered his next move. The reverberation of the water enveloped him, and he began to feel a part of it. A giddy mix of emotions—elation, wonder, fear—swam in his head. He decided again not to move forward. But then he did.

Some inner wildness had taken over. As he advanced, choosing his steps carefully, tufts of artemisia dangling from the clefts caught his eye. He plucked a few leaves, bit down on them, and soon felt the sedative effect of their bitter juice. Time slowed. The slope was not his enemy. He was a part of it.

He crept forward and, when he reached the small ledge, about three inches wide, planted his heels on it. Then he shuffled sideways, like a crab, toward the precipice—thirty feet to go, twenty feet, the water beside him now white and agitated as it sped to its threshold, ten feet. At last the edge was right in front of him. Legs firm, body stiff, arching, he peered over. His eyes bored into the billowing free fall, and he watched the spill separate into streamers, comets of water whose tails refracted the sunlight.

As the creek flowed past him on its grand adventure, his body and soul seemed to hang there, somewhere in between terra firma and air infinitum. Another current—Emerson’s words—he well knew: “In the woods, we return to reason and faith. There I feel nothing can befall me in life—no disgrace, no calamity (leaving me my eyes)—which nature cannot repair. Standing on the bare ground—my head bathed by the blithe air, and uplifted into infinite space—all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eyeball.”

Muir was nothing; he saw all. He lost any sense of the passage of time and later could not remember his retreat from the ledge. Although a slip of the heel could have sent him over with the powerful creek, the magnificence of the fall—its ever-active and changing form, its rumble and sudden silence, its action and refraction, its immediacy and its distance—had him spellbound.

So many stimuli bombarded his senses that there was no room for fear. Instead, where earth and water met air and light, Muir, with the religious fervor of his upbringing, saw God. He saw God in the fragmentation of the stream and in the rays of the sun passing through to make vivid rainbow beads. He saw God in the rebirth of the stream suddenly expelled from earth, as death and a new life, a new journey, were simultaneously manifest.

Around dark, Muir and Carlo returned to camp. The exhilaration of the afternoon ebbed, and a deep exhaustion settled in. It had been “a most memorable day of days.” Muir had had “his first view of the High Sierra, first view looking down into Yosemite, the death song of Yosemite Creek, and its flight over the cliff,” each a lifetime moment, and all in all “enjoyment enough to kill if that were possible.” He felt he had been admitted to a place of divine beauty, and it was already reshaping the way he perceived the world and existence, just as Emerson had said it would in his essay “Nature.”

That night while Muir’s tired body slept soundly, his mind raced. The mountain he was on crumbled in his restive dream, and an avalanche of water and stone swept him into the sky. He tumbled and free-fell into the valley, not from the mountain but with it. They were one.

In the days that followed, Muir’s mind was ablaze with new sensations and thoughts. On July 27, he would write in his journal, “When we try to pick out anything by itself we find that it is bound fast by a thousand invisible cords that cannot be broken, to everything in the universe.” It was a line echoing and perhaps inspired, whether consciously or subconsciously, by his literary hero, Emerson, who had written, “Nothing is quite beautiful alone; nothing but is beautiful in the whole.” And Muir would later rewrite the line, as it appears, famously, in his book My First Summer in the Sierra: “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe.”

While Muir was getting “hitched to everything” in the metaphysical sense, the nation was actually getting hitched. Just two months before Muir peered into Yosemite Valley, Leland Stanford had hammered in a golden spike at Promontory Summit in the Utah Territory, completing the transcontinental railroad after a seven-year rail-laying frenzy ignited by the 1862 Pacific Railroad Act, passed for that purpose. This feat spawned the Gilded Age and its explosive economic growth, political and market upheaval (including depressions following panics in 1873 and 1893), and unprecedented tourism. Now passengers, mail, and freight could zoom from coast to coast in six days, while the cost of crossing the country fell from $1,000 to $150. The railroads hyped the West to drum up traffic, and a new wave of settlers—farmers, ranchers, loggers, and miners—poured in from the East Coast and Europe to seek their fortunes.

They came to be transformed. But they would do the transforming, and the quantum leap in the nation’s ability to extract and transport natural resources would help them ravage the landscape at a record pace and on an industrial level—right before the eyes, so recently returned to sight, of John Muir.

___________________________

From Dean King’s Guardians of the Valley, available from Scribner (out in paperback March 21).

Dean King

Dean King is the nationally best-selling author of Skeletons on the Zahara and The Feud and a biographer of the British novelist Patrick O’Brian. His book Guardians of the Valley: John Muir and the Friendship That Saved Yosemite (Scribner, 2023) will be released in paperback on March 21.