Slippery, Slimy and Sublime: On Our Fascination with Eels

Ellen Ruppel Shell Goes Deep on the Cultural Life of the Anguillidae

“All the rest is hypothesis and dream.”

–Louise Glück, “Theory of Memory”

*Article continues after advertisement

The French chef Adrien Ferrand grew up with eels, which he caught with his father while on summer visits to his grandparents’ home in Burgundy. His grandmother prepared them, but not to her grandson’s liking. “They were no good,” he told me. At fourteen, Ferrand determined to do Grand-mère one better and attend culinary school. Fifteen years later, his Restaurant Eels was lauded by critics as among the best bistros in Paris, even in the world. Intrigued, I agreed to meet Ferrand at his workplace and taste for myself.

Tucked into a stark first-floor corner space flanked by a motorcycle stand on one side and a barbershop on the other, Restaurant Eels had a laid-back, Scandinavian vibe and a youthful clientele who clearly knew a thing or two about food. And Ferrand’s food was worth the trip—including his signature smoked eel with Granny Smith apple, licorice root, and hazelnuts made with European eel cultivated on a small farm in Greece. Each plate was beautifully composed, essentially a work of art. But I’ll admit to a pang of disappointment. For once the dinner crowd thinned and we had a chance to talk, Ferrand confessed he had not given eels a lot of thought.

Eels have an uncanny knack for grabbing our attention and sticking in our minds.So why name your restaurant Eels, I asked?

“Ah, that,” he said. “Of course. Eels are something very special. They speak to me of something I can’t explain, something beyond words, perhaps beyond memory. I’m sorry I can’t say more, but I am a chef, not a poet. Maybe you would like a dessert?”

Something beyond memory? Not a poet, perhaps, but certainly of a poetic sensibility. What is it about the eel that brings out the poet in us? Nothing like us or what we hope to be, the eel is nearly impossible to anthropomorphize. It has neither the brainy quirks of an octopus nor the childlike playfulness of a dolphin. It’s not fierce like the shark, nor majestic like the tuna. So why did it draw in Ferrand, as it has so many artists?

My first literary encounter with the eel came by way of the German novelist Günter Grass and his chilling bildungsroman The Tin Drum. Given the reach of that remarkable novel it would not surprise me to hear that it was your introduction, too. If so, you surely recall the shocking role eels played in the book. The story opens abruptly in an insane asylum in what was then Gdansk, Poland. There we meet Oskar Matzerath, the thirty-year-old protagonist who has confessed to a murder he did not commit. Oskar, who identifies as a dwarf, is grandiose, salacious, and a thoroughly unreliable narrator. When on his third birthday his mother gifts him with the titular tin drum, he throws himself headfirst down the cellar stairs to fend off adulthood and the horrors it brings. (Significantly, the scene is set in the 1930s and the Holocaust looms.)

From there, the larger-than-life story unfolds in a series of harrowing vignettes. The one I’m thinking of places Oskar in the company of his stepfather, Alfred; his mother, Agnes; and his mother’s cousin and paramour, Jan. It’s Good Friday, and the little family marks the holiday with a stroll along the Baltic coast. They come to a jetty and scramble from granite block to granite block all the way to the breakwater. There they stare in fascination as an old man tugs at his fishing line, pulling hand over hand against the pounding surf.

Time passes, and a severed horse’s head surfaces above the waves, so fresh its mane gleams black in the sun. The family watches in horror as the fisherman, grinning demonically, yanks the ghastly skull to shore and pulls eel after eel from its gaping mouth, nose, and eye sockets. Agnes, who is pregnant, bends from the waist and pukes her guts out. Oskar stands by, robotically banging his drum while his stepfather, impervious to his wife’s distress, bargains with the fisherman for four eels to boil up for their Lenten supper. Later that evening, Agnes refuses to eat the eel, and vows to never again eat fish of any kind.

A few weeks later, Agnes reverses herself and gorges compulsively on fish of several varieties, notably eel. After a month or so, she and her unborn child die of what a doctor diagnoses as “fish poisoning.” At her funeral, Oskar imagines his mother bolting up from the open coffin and vomiting white bits of eel. To our great relief, she stays put in her casket, “to bury the eel beneath the earth, so there might at last be peace.”

There are many interpretations of this passage, some involving sex, and few convincing. No matter. For readers like me, the memory of Grass’s eels is indelible. We are horrified by the fisherman and the horse’s skull squirming with eels, but also mesmerized: eels have an uncanny knack for grabbing our attention and sticking in our minds. It’s doubtful that many other creatures—let alone another (freshwater) fish—would evoke such a powerful and lasting image. Nor was The Tin Drum unique.

The 2017 film A Cure for Wellness bombed with many critics and at the box office, but movie buffs brave enough to see it were unlikely to forget the film’s protagonist floating in an isolation tank, where he is swarmed by a posse of three-hundred-year-old “therapeutic” eels and nearly drowns. In this film the eels steal the show: as one critic opined, “I think you need to start with the eels. The eels are everything in A Cure for Wellness. They are what I am going to remember from this oddly forgettable movie, and they are a metaphor for the film’s promise and failure to live up to that promise.”

Which leads one to wonder: What exactly did the eels promise? More questions are raised by the 1984 blockbuster Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, with its gluttonous “eel eater” digging into copious platters of “snake surprise,” a banquet dish of juvenile eels oozing from the guts of a casually coiled boa constrictor. Marvel Comics had its own very special take in the form of “the Eel,” an alias used by two slimy supervillains, the first appearing in 1963, the second in 1983.

In his 2017 essay on animal metaphors, the American literary scholar Ryan J. Stark calls eels “weird” and “creepy,” both common descriptors, especially among those who have not spent much time with them. Those who have spent much time with them, by contrast, tend to take a more nuanced view. The British author Graham Swift, an avid fisherman, has had more than a few close encounters with the eel. In Waterland, his tragic masterpiece of doomed love, betrayal, and madness, Swift does for the metaphorical eel something like what Herman Melville did for the metaphorical whale. His novel centers on Tom Crick, a history teacher on the verge of (involuntary) retirement who strives to awaken the flagging interest of his students with stories of his troubled and traumatic childhood. He says that father was a superstitious man, “and since my mother’s death, which was six months before we lay eel traps under the stars, my father’s yen for the dark, his nocturnal restlessness, had grown more besetting.”

Through Crick, Swift describes the eel as “not an unhandsome creature. It’s sleek and smooth-skinned. It has little glimmering amber eyes which, for all one knows, could be the windows of a tiny eel-soul. It has little panting gills and, behind them, delicate whirring pectoral fins.” As was Oscar in The Tin Drum, Tom is an unreliable narrator—one of his students accuses him of telling self-serving fairy tales. But that’s the point. For Swift, the mystery of the eel represents the option of not-knowing, and of trading off the very human demand for certainty in exchange for a sort of peace. He writes that the eel possesses an “instinctual mechanism more mysterious, more impenetrable perhaps than the composition of the atom…there is much the eel can tell us about curiosity—rather more indeed than curiosity can inform us of the eel.”

The Swedish journalist Patrick Svensson touched on similar themes in his memoir The Book of Eels, in which he recalls fishing for eels with his father in a stream near his childhood home. His eel memories are fond, but he acknowledges that others feel less comfortable and traces this discomfort to what Freud (who you’ll recall had his own eel encounters) called “unheimlich”: the unease and uncertainty that overcome us when what we see is at once familiar and contains an element of strangeness. There is merit to this argument. We often fear what we don’t know, and the eel, while familiar, is not easy to know. (Graham Swift implies in Waterland that the eel is not knowable at all.) But I’m not sure we need to invoke Freud to explain the eel’s uncanniness.

Like most primates, humans evolved to fear snakelike objects, of which the eel is an obvious example. Perhaps that explains why the word “Anguilla” takes its root from the Latin “ango,” or “to strangle.” So the real question is not whether or why eels are frightening. Of course they are! The real question is why a legion of scientists, historians, anthropologists, entrepreneurs, artists, and—yes—authors are so utterly bewitched by them. To begin to answer that question, one might turn to the work of the Hungarian philosopher Aurel Kolnai, who points to the paradox that things that disgust us also hold a “curious enticement.” (If you doubt this, consider the popularity of reality shows such as Fear Factor, a TV series in which contestants compete by gulping slurries of pureed rat and bedding down in coffins stuffed with cow intestines.)

In the case of eels, I concede that disgust may play a role for some readers, moviegoers, and reality TV fans, and perhaps also for some authors and filmmakers. But like me, these are interlopers, or, at best, bystanders. For the scores of actual eel people I’ve come to know, it is something else altogether. Naturally, they are captivated by the eel and its ways, but it’s more than that. For them, it seems, the pursuit of the age-old “eel question” is something closer to a religious quest.

__________________________________

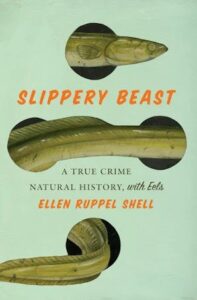

From Slippery Beast: A True Crime Natural History, with Eels by Ellen Ruppel Shell. Copyright © 2024. Available from Abrams Books.