We stay off the interstate, stick to Highway 30, rolling into the treeless western Wyoming hills, not hardly a house in sight, and I breathe 4–7–8 again, and I think about the way Liandro was shuddering when I put the Guiding Star into park and the skinny old white man got out of his truck grinning grimly. Light glimmered bright blue off Bear Lake.

“It’s not my fault that kid messed with the wrong people,” I tell Flip, and he gives me a long, considering look—who am I trying to kid, he wonders, and rolls on his side so the heater can blow on the back of his neck.

Then out the window I see a big billboard for Little America—not far across the Wyoming border—and I think, hell, yes, maybe I’ll stop early for the night, get me and Flip a motel room with a good shower in it.

I’ve always had a fondness for Little America. It’s a vintage truck stop, with a filling station, a 140-room motel, and a travel center where you can get some food and buy some trinkets. Legend has it that in the 1890s, when the founder of Little America was a young man out herding sheep, he became lost in a raging blizzard and was forced to camp at the place where the Little America now stands. I read about this on a plaque in the motel lobby when I was a child, and it caught my fancy, and even today I can practically quote whole pieces of that plaque, how, shivering in the midst of the blizzard, the young shepherd “longed for a warm fire, something to eat, and wool blankets. He thought what a blessing it would be if some good soul were to build a haven of refuge at that desolate spot.”

Honestly, I don’t know why I was so taken with the place. It was maybe mostly the billboard advertising they did—they had billboards all along the Lincoln Highway and I-80, featuring a cartoon penguin with an outstretched, welcoming flipper, and the more billboards you saw the more you felt that the place was exciting and an Important Landmark, and possibly magical.

My mom and I stayed there maybe five or six times when I was growing up—sometimes only a few days or weeks, sometimes a month or more—and it has a little homelike glow of nostalgia for me now. There’s a green Sinclair Brontosaurus outside the motel, a cement statue about the size of a horse, and kids are allowed to climb on it. When my mom and I stayed there, I was always king of that Brontosaurus, just sitting astride his back and riding the hell out of him, and of course other children would come along and want to get up on him, too. So I met kids from New Jersey and Chicago and Houston, kids going on vacation to Yellowstone or Flaming Gorge, kids fleeing with their mothers from dads who wanted to kill them, kids who wanted to convert everybody to Jesus, kids who had an eye out for some animal or small creature they could torture. I even met a little girl from Japan once, she didn’t speak any English but I talked to her in my language and she talked to me back in hers, and I remember this being one of the most pleasant conversations I have ever had.

I’m adrift in these reminiscences when some crap begins to fall out of the sky. It’s not sleet or snow this time, but something I’ve never seen—dark flakes of some kind of substance come down like leaves from a tree and they make a muddy smear when my windshield wiper pulls them across the glass. I can squirt it off with the windshield wiper fluid, but at this rate I have to wonder whether the fluid will last another nineteen miles to Little America. A few drivers are already pulled over to the side of the road, and I pass a family van with all their belongings in cardboard boxes roped to the top of their vehicle. The boxes look like they’ve seen some extreme weather conditions, and also they are spotted in a way that suggests that they’ve been passed over by some flocks of birds.

I don’t know what, exactly, is raining down this time. Maybe detritus from the typhoon off the northwest coast, or ash from the Mount Silverthrone volcano up in Canada. But I reckon we’ll all get used to it and adjust our expectations accordingly. It’s true that the world isn’t in great shape, but I’ve read that it’s not the worst it’s been—not as bad as it was in 536 C.E., when catastrophic volcanic eruptions caused a short-term ice age, devastating famine, and so forth. Probably not as bad as it was in 1349, maybe not even as bad as 1520—but we all sense that worse times are ahead.

No doubt, a day of reckoning for mankind is coming, yet even for those of us who accept the inevitability of mass human death, there’s still a cautious hope; we’re waiting to see how Armageddon plays out, keeping an eye open for ways it might turn to our advantage. Even in the worst-case scenario, odds are that at least a few of our kind will struggle on long enough to evolve into creatures suitable for whatever new environment is ahead. I’m no evolutionary biologist, but I have faith in our species’ stick-to-it-iveness.

I put my head down and keep driving, leaning forward over the steering wheel, the better to squint through the translucent smear of silt that the windshield wipers leave as they make their sweep. I may only be going ten miles an hour, but I am a man hell-bent on a destination.

______________________

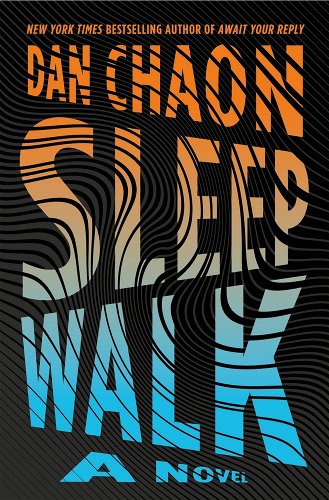

Excerpted from Sleepwalk by Dan Chaon. Copyright (c) 2022. Reprinted with permission of Henry Holt & Company.