He still wished for stability, which surprised him. Prison, for all its horrors, offered certainty as indisputable as the stone and metal. Hate it or love it, government had been there, giving structure, consequence, and a framework for living that one could either jibe with or not. This new world lacked such certainty. Indeed, even the event’s calculation determining who lived and who didn’t wasn’t so distinctly black and white. Best Charlie could deduce, the judgment, more or less, had something to do with identity in America. Didn’t matter what race box a person checked on a voting form. While not everyone checked white, none of them aspired to check black. Not in America. Not in a courtroom or a country club. Not on a back road or in a bank. Not in any of America’s serene places, sparkling and forbidden. No one else wanted to be a black person in America. And everyone knew that fact, however cruelly the result played itself out. No matter the worry in their lives, they could all but count on a voice, redemptive and default, whispering as a comfort to their hearts: At least I’m not them. And so they carried on, injustice as natural and inconvenient to their lives as a bit of rain.

Seemed to Charlie the event had something to do in dealing with the fact of that.

So people made their own rules. Even local news devolved into what felt less like reporting than sermonizing, talking heads too quick to thrust opinion without substance, emphasizing that no one runs the country anymore. No one rose to make a new president, no Democrats, no Republicans, no halls filled with representatives. No unity at all.

The event shattered many, many things, but none more than the United in United States. Physically and philosophically, all governing deteriorated. Titles evaporated, as did sovereign formalities; even the language of government would be gone entirely in a generation, as one no longer needed to declare one’s independence or stand atop a bill of rights. Aside from the Registry of Those Remaining, an online index of all the people still alive in the country, nothing felt united at all. Already, authority passed down to local leaders and activists whose tenacity to make a difference was matched only by the imprecision of their management. No real union or clarity, a reality in existence long before all the white folks marched into the sea.

Absently, Charlie pondered unity as he mapped his journey, deciding to brave at least some unaccounted areas through Toledo, Fort Wayne, and Gary. Unity, he supposed, began with knowing, and knowing dulled all risk in the grind of a purpose. In truth, he wasn’t afraid of those unknown roads, but he wrung his hands at the thought of where the roads led. To a place where voice in the dark became a person looking back at him. He feared seeing his daughter’s face. Feared recognizing their differences as much as their similarities. Feared experiencing the impact of his absence. But, as fear had all his life, the difficulty presented an opportunity for a quiet dignity. Dignity he’d need if he planned to look his daughter in her eyes. So Charlie chewed on the inside of his cheek, packed a small bag, left notes for his students and colleagues, and went on with the business of getting on the road. All but ready to leave, he got back out of the car. He returned to his office for the letter addressed to him, tucked in his filing cabinet, still in the plastic bag branded sussex state prison. The only letter he’d ever kept. The only proof that he and Elizabeth made anything worth salvaging.

Charlie took in the city on his way out. Even at the early hour, D.C. pulsed. Gospel music spilled out of barbershops. Electric scooters zoomed down sidewalks and bike lanes. A line of people wrapped around a McDonald’s with its arches torn down, where somebody’s grandma captained the kitchen making enough cheese grits and biscuits to feed the neighborhood. The city almost resembled life before the event—with subtle differences. There were no more homeless people. Less trash littered the shoulders, because no one mass-produced single-use plastics and containers anymore. The biggest difference, he determined, was better felt than seen. The only word he could think to describe life was easier. On the rare occasion that he spoke to someone about the event, most of them would lower their eyes, say how big a shame it all was, but go on to soberly acknowledge how free they felt. Free to walk alone at night. Free to climb a tree. Free to fall asleep somewhere in the sun. Freedom that inspired them to change their names, calling themselves after plants and animals, looking, Charlie suspected, to reclaim something true about themselves that now they could.

__________________________________

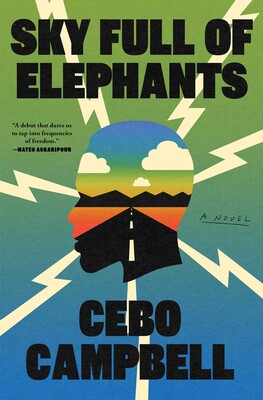

From Sky Full of Elephants by Cebo Campbell. Used with permission of the publisher, Simon & Schuster. Copyright © 2024 by Cebo Campbell.