Over the last 50 years, contemporary Pacific Islander poets have crated a vibrant and diverse range of poetry, fiction, and nonfiction. Even though this literature has circulated within and beyond the Pacific, it still remains marginalized in studies of global literature.

This folio of poetry presents a modest sampling of five poets who have genealogical roots in Samoan, Maori, Chamoru, and Tuvaluan heritages. Several of them currently reside in Hawaiʻi and Aotearoa/New Zealand, while one lives in California. Even though the themes the poets address—including identity, family, home, and culture—are prevalent in Pacific literature, each writer approaches these topics with their own unique style and voice.

I hope you will enjoy this collection and seek out the work of these writers both online and in print.

—Craig Santos Perez

William Alfred Nu’utupu Giles is a Samoan-American poet from Honolulu, Hawaii. He is a Kundiman Fellow who studied with the First Wave program at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Will works as the Workshop Coordinator for Pacific Tongues on Oahu, is a Brave New Voices International Poetry Slam Champion, and is the 2015 National Underground Poetry Slam Champion.

Prescribed Fire

as some of the tallest trees in the world

redwoods can grow to over 350 feet above the earth

yet their roots, on average only travel 10 feet into it

in isolation, it should be physically impossible for them to stand

however, these enormous trees do not grow in isolation

their roots, each only a single inch thick

wraps around the roots of it’s neighbors

a stubborn foundation of brown fingers

clasps an underground stand

and grows

my family is a group of redwoods

that sought god instead of ground

when my mother immigrated to the united states from Samoa

she taught none of her children how to speak our native tongue

now 26 years later

I cannot feel the hands

of the land I come from

how do you stand when your roots

have been burned away

today I am a tree toppling over

a man cut off at the knees

stuck between a loved language lost

and a sky still out of reach

and that is the true legacy of world war II in the Pacific

a generation of Islander and Asian immigrants who learned

that their foreign accents and different skin

could mean your family in internment camps

learned their place in this society

could only be bought with blood in uniform

they learned their citizenship papers

would only be traded for their severed tongues

it is true

that the branches of a tree may spread no wider than it’s roots

but when parent countries

are just another word for poverty

when you are made to choose

between putting your children in culture or clothing

which blood would you want?

this is how redwoods fall

they forget the only reason

they are able to stand and defy common logic

is how well they hold one another

in Hawai’i

an immigrant mecca

where so many of us try to stand with a lost past

we have old weeping banyan trees who also came from across that sea

these banyan’s start from seeds that are blown to other canopies

and without pity or regard for past

they create their own way to the ground

sprouting aerial roots that crawl to the earth

and make a home wherever they find it

in Polynesia,

we have always learned from the earth around us

so now I do not lament my lack of roots

instead, I grow them myself

so every day I am a windblown seed

I am “foreign” accents and different skin

every day I fall towards the earth and am reborn in dirt

I am blood in uniform and severed tongue

every day, I am the blood I want

every day, I look around

hold on tight to those I love

and I grow

into an extended

family

tree

Tusiata Avia has published two books of poetry, Wild Dogs Under My Skirt and Bloodclot and two children’s books. Known for her dynamic performance style she has also written and performed a one-woman show, also called Wild Dogs Under My Skirt. Tusiata has held a number of writers’ residencies and is regularly published in international literary journals and invited to appear at writers’ festivals around the globe.

Demonstration

The thing is

even after all these years

even after all you know

after all the times you have spoken

to classrooms full, divided them into four

pointed to one quarter and said:

All you people have been sexually abused

to get the message across.

And then listened to them unbutton their stories

shame and anger lighting them up like brilliant torches

firing the night inside them

the blackness all around

a thousand bright bombs falling from the sky.

The thing is

after speaking through the mouths of every kind

of good girl

girl child

bad girl

slut.

After reading

and talking and posting

the drain out of it

and then have it tunnel

back up through you like a worm

as big as an earthquake

and disappear again.

Even after marching

at the anti-rape demonstration today

with your six year old daughter’s hand in yours

and a sign pinned to her small chest:

‘Believe Survivors’

even now, as you stand here in the Square

you wonder

because it was 25 years ago

and you did kind of like him

even though he was a bit of a Fob.

You wonder

because it was the Samoan Students’ Association so’otaga

and you were the president the year before

the first woman, the first New Zealand-born, the first afa kasi

and it was in your home town

and you helped him find a place to stay

you picked him up from the airport

it made you feel helpful

and kind and involved

and you did kind of like him.

You wonder

because after one of the association parties

you were a bit drunk and ended up sleeping

in the lounge of the house he was staying in

and kind of hoping something would happen

in the same way you would hold a tiny, fragile creature

in your loosely caged hands

maybe a butterfly or a newborn mouse

and offer that delicate thing up

to him and hope he might

ease it gently from you

so as not to hurt it

and maybe he’d even offer something back.

Because of that

you let him kiss you

on the floor

before it turned

from a hopeful kiss with a guy

you kind of liked

to him on top of you

and you saying:

No, stop it!

Because he’d stopped kissing you now

and even though he was shorter than you

he was a hell of a lot stronger than you could’ve imagined

and was prying you apart.

You wonder

because when you realised what was happening

you knew you didn’t want that

and you told him: I don’t want this. Stop!

But the thing is

he didn’t stop

he just kept going

he didn’t say anything

and you swore at him:

Fucking get off me!

I don’t want this

I don’t want this

you said:

I don’t want this.

But he just kept going

and didn’t say anything at all

until he was finished

when he rolled off you and said:

It’s no big deal.

That’s all he said.

And you wonder

now, in the Square

if you could’ve fought harder

or not slept in the lounge

or not let him kiss you

or not kind of liked him

or not hoped he might like you too.

And you remember

that the next morning

when you got to your mother’s place

you looked at yourself in the hall mirror and thought:

I’ve just been raped.

And then you had a shower

and changed into your church clothes

and went to the church service with everyone else

and he was there.

And when you returned to teachers’ college in Auckland

you couldn’t function

you kept seeing him in the cafeteria

and everywhere

and you kept cracking up

and missing classes

and when you finally went to the counsellor

and talked about it

she said: Have you heard yourself?

You keep saying:

It’s no big deal.

So, today

twenty-five years later

as you watch this young woman

in the Square

the age you were then

take her clothes off in protest

you wonder again

whether it was rape

and whether it might have been your fault.

IT WAS NOT MY FAULT IT WAS RAPE IT WAS NOT MY FAULT IT WAS RAPE IT WAS NOT MY FAULT IT WAS RAPE IT WAS NOT MY FAULT IT WAS NOT MY IT WAS NOT MY FAULT FAULTITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEWASWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASNOT

MYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASRAPEITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPEITWASNOTMYFAULTITWASRAPERAPERAPERAPE.

Serena Ngaio Simmons is an accomplished spoken word artist of Maori and European descent born and raised on Oahu. Serena has attended and competed in the Brave New Voices international spoken word competition in 2011 and 2012. Serena is currently pursuing her Bachelors in English at the University of Hawaii at Manoa.

Aotearoa Love Poem

The first time I fell in love,

I was on a beach in Aotearoa

staring at rock faces spread out like a sun dial

in front of me.

It was a Sunday afternoon in June

flakes of pipi shell smiling face up through the sand

the ocean,

tossing bits of salt at my neck

my friend,

like maroro in the frigid shore breaks

All I could see was the cliffs

those moss shouldered giants

nga kaitiaki strong in their posts,

clever anglers, my land,

fishing half of my heart out while I gawked

mouth agape at all that prowess,

they hooked a slice out of me

when I wasn’t paying attention,

heaved it in

kept it for themselves.

Feet buried in clay shaded coast,

I made sure to stain my teeth

with every bit of it, lodge the sand

further into my nails,

swallow the saltwater as it dripped from my bangs,

keep whatever I could without taking, if only

I didn’t have to leave.

I wouldn’t have been so selfish during my visit,

forgive me,

this is love

and I don’t know what I’m doing.

It has taken me eight years

to find home,

eleven days to learn just how real

love can be, how much

howling a heart is capable of

when it is missing roots, the hours spent

counting the days until I have to climb back on that plane

my chest

is a halved quarry I have been trying to make rich again.

I am finding it harder every day to breathe through a fraction

this must be

what all my friends were talking about

what Neruda was saying when he wrote,

don’t go far off… the smoke that roams

looking for a home will drift into me

Aotearoa, you’ve baked a chimney

into my throat, filled it with drift

there is a fire crackling

behind my teeth and I am too afraid

to show it to anyone lest they try to suffocate it

conversations are brief and always end smelling like

fresh smoke, it is getting harder

to find people who understand this

We can all speak distraction

few people can speak homesickness

sunrise on the pae pae

kumara and table salt

cups of milo in the den

and your mountains

nga maunga

sneaking away a piece of me

a reminder

to hurry back

Courtney Sina Meredith was born in 1986, she launched her first book of poetry Brown Girls in Bright Read Lipstick (Beatnik Publishing) at the Frankfurt Bookfair in 2012, her play “Rushing Dolls” (Playmarket) was anthologised later that year. She was the Bleibtreu Berlin writer in residence 2011, and in 2014 she was invited to the House of Lords by the BBC to discuss the cultural future of Britain. Her poems have appeared most recently within Atelier (Italy), I Sit Like a Garbage God (Brussels) and Best Essential New Zealand Poems: Facing the Empty Page (NZ).

SHADOW ON THE HEART

We’re in a hospital

going around touch the ground

no patients staff sit everywhere

alike tables amounting to steam.

Staff walk everywhere

late nights bad ideas

you want to order?

I’m not eating remember

Brick Lane antiques

bottom floor coffee

in the dark it was a decent

place to fall for shiny things.

A. she hasn’t lived our life

so she just doesn’t understand.

B. different chambers of course, septum

the dividing wall is what she’s like.

C. why care?

Thank you for waiting

sorry about the wait

sorry about that. Our fault

old computers bad habits.

They got held up this morning

a peculiar case a sweetheart.

Is that a species known to be friendly? Tiger goldfish

eat plastic soldiers. New women come to relieve

those and their friends gently ushered away.

Where do they take the receiving chambers

for a walk on the beach for a day in the sun

for a break from the blood flowing through.

Clarissa Mendiola is a Chamoru woman who was raised in California. Through segmented essays and poetry, her work explores ideas of cultural identity and ethnic purity via memory, myth, oral and written history, and the ways in which all of these things work toward or against the overarching question–what does it mean to be Chamoru? Her lineage includes the Santos family of Talofofo (Familian Manok) the Mendiola family of Barrigada. She has an MFA in Writing from California College of Arts and currently lives in San Francisco where she thinks, writes, and dreams about Guahan.

REUNION

at a barbeque they sing

karaoke in the back

kitchen framed only

by waxed edges of looming

jungle wailing

their taut brown heads

cocked back releasing jagged

notes into dense night they

rest their arms on each other

on dad his fair spanish

skin made fairer by three

and a half seasons of california

coast and the contrasted dark

trunks of his friends’ arms

i wonder what distances

they bridge with this affection

what loom of land focuses

what species of bird indicates

approach

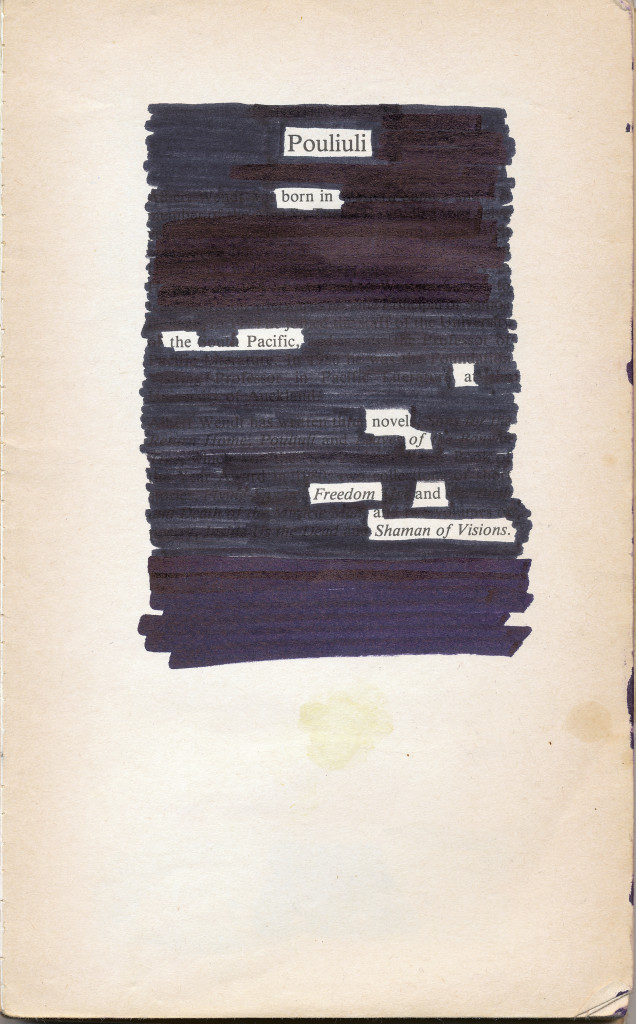

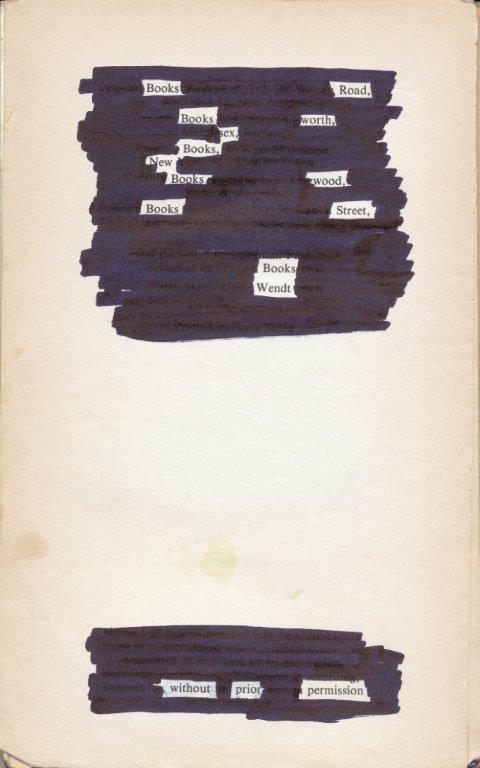

Dr Selina Tusitala Marsh is an Auckland-based Pacific poet and scholar of Samoan, Tuvaluan, English, Scottish and French descent. She is the author of two collections of poetry, Fast Talking PI (2010) and Dark Sparring (2014). She is a professor of Pacific literature at the University of Aukland, New Zealand.