Silvia Garcia-Moreno on Dracula’s Depictions and Descendants

Vampires! Vampires! Vampires!

Tracing the genealogy of vampires is complicated because it is initially murky. Different cultures have stories about blood-sucking fiends, but not all creatures that suck blood are vampires. In Europe, reports of vampire attacks in the early eighteenth century, including the case of the Serbian vampire Arnold Paole, fuelled many conversations on their nature. Accounts of vampires were further popularized by the publication of Dom Augustin Calmet’s 1746 book Dissertations sur les apparitions des anges, des démons & des esprits, et sur les revenants et vampires de Hongrie, de Boheme, de Moravie & de Silésie (Dissertations on the apparitions of angels, demons, and ghosts, and on the revenants and vampires of Hungary, Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia).

Nick Groom, in The Cambridge Companion to Dracula, writes that by the mid-eighteenth century, “vampires had become a staple of travellers’ tales of central and eastern Europe.” But these vampires were not the same as the ones we know nowadays.

Slavic and Hungarian folklore is rife with stories of wandering corpses and people that come back from the grave. Like all oral narratives, these stories are peppered with variations and contradictions. However, looking at numerous tales, it becomes clear that vampires seem to be predisposed to their condition. Sinners, suicides, and people who are otherwise troublesome in life are prime candidates for reanimation. Illegitimate offspring, the seventh child in a family, or babies born with cauls are likely to become vampires. The list of predispositions toward vampirism is expansive and sometimes baffling. Paul Barber’s Vampires, Burial, and Death mentions accounts of corpses unearthed because they were alcoholics. Sometimes, vampires came back from the grave to complete unfinished business.

Whatever the source of their vampirism, when these corpses escape their coffins they drink the blood of the living, often targeting their own family members. However, these creatures do not turn humans into members of their vampire army, nor are they particularly seductive.

Calmet explained that “the vampire has a sort of hunger, which makes him eat the linen which envelops him.” These creatures sometimes drank so much blood it oozed through their pores. When they crawled out of their graves, vampires might wear a shroud, or the clothes in which they were buried, which in the account of a shoemaker of Silesia, “had a repulsive smell.” Calmet described vampires as ruddy, “without worms or decay; but not without a great stench.”

These early vampires—animalistic, voracious, malodorous—have more in common with zombies from a George Romero film than with Bram Stoker’s wealthy Count Dracula.

Lord Byron’s 1813 poem “The Giaour” neatly summarizes the vampire of the early nineteenth century:

But first, on earth as vampire sent,

Thy corse shall from its tomb be rent:

Then ghastly haunt thy native place,

And suck the blood of all thy race;

There from thy daughter, sister, wife,

At midnight drain the stream of life;

Yet loathe the banquet which perforce

Must feed thy livid living corse:

Thy victims ere they yet expire

Shall know the demon for their sire,

As cursing thee, thou cursing them,

Thy flowers are withered on the stem.

One of the first turning points for vampire fiction was the release of John William Polidori’s “The Vampyre” in 1819. The story stars Lord Ruthven, an aristocrat who drains his bride’s blood on their wedding night. Polidori was one of the guests who attended a famous gathering at Lake Geneva that included Lord Byron, and where Mary Shelley began penning Frankenstein. Polidori, who at the time was Byron’s physician, took as his inspiration part of a vampire story that Byron himself had written. As Brian J. Frost notes in The Monster with a Thousand Faces, by modeling his villain after Byron, Polidori turned the vampire from an “uncouth, disease-ridden peasant” into a suave nobleman.

Lord Ruthven was not the first sexy vampire; Goethe’s “The Bride of Corinth” (1797) is a poem about a young bridegroom who journeys to a town to meet his intended. A mysterious woman seeks him out at night and they have sex. It turns out that she is his bride, who has died before his arrival. She is determined “to draw the blood from his being,” and his eventual fate is an untimely death. Sex and death are therefore linked in this poem, which follows traditional beats of vampire stories, such as the dead returning to life because of unfinished business and targeting those close to them.

But even if Goethe came first, the importance of Polidori’s “The Vampyre” was tremendous, and he went on to influence many others. Théophile Gautier’s story “La Morte amoureuse” (1836), published in English as “Clarimonde,” offered us a sophisticated female vampire who sucks the blood of a young priest. Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla (1872) had an identity-changing aristocrat who drains the blood of other women. In short, as Christopher Frayling explains in Vampyres: Lord Byron to Count Dracula, nineteenth-century romanticism fully morphed the hideous vampire into a seductive villain.

What these writers did not do was turn vampires into vectors of contagion. Gautier’s young priest may be haunted by the memory of Clarimonde, but he does not become a vampire himself. Neither does Laura, the heroine and narrator of Carmilla. As for Lord Ruthven’s bride, she simply “glutted the thirst” of a vampire.

When Dracula was published in 1897, it injected an element into vampire narratives that would change these creatures forever: vampires as a virus.

*

Stoker’s innovative use of a viral vampire seems couched in the many scientific elements of the novel. The end of the nineteenth century was an era of great knowledge leaps, and Stoker mines both traditional folklore and modern medicine for his horror story. It did not hurt that he had several relatives who were doctors, and who likely provided material for his writing.

The scientific and medical elements in Dracula are numerous, and are tightly woven into the narrative, beginning with the character of Dr. Seward. Seward works at an asylum located next to the ancient, ruined Carfax mansion Dracula has purchased, and oversees the care of Renfield, a homicidal patient who might necessitate a new classification, that of a “zoöphagous (life-eating) maniac.”

Seward’s profession allows readers to hear about some of the cutting-edge science of the era. Renfield must be “trephined”—that is, a hole must be made in his skull. In another scene, the heroes donate their blood for transfusions in an attempt to save Lucy Westenra, who is suffering from severe blood loss. Abraham Van Helsing injects the young woman with morphine to keep the patient asleep.

Other scientific concepts and concerns of the era that manifest in the novel include eugenicist ideas. Eugenics, the practice of attempting to breed superior human beings, may seem archaic to modern readers, and replete with sexist, racist, and ableist underpinnings. Nevertheless, eugenics was considered a serious science and widely accepted into the twentieth century, when it led to, among other things, sterilization laws and anti-immigration policies.

Thus, it’s no wonder that Dracula is described by Van Helsing as “a criminal and of criminal type. Nordau and Lombroso would so classify him, and quâ criminal he is of imperfectly formed mind.”

Cesare Lombroso’s 1876 theories posited that criminality was inherited, and that criminals possessed atavistic traits that could evidence their nature. Dracula is therefore described as a man with a “cruel-looking” mouth, lips “whose remarkable ruddiness showed astonishing vitality,” “extremely pointed” ears, and “coarse,” “broad” hairy hands with squat fingers. These traits hint at the Count’s hideous nature. Renfield’s madness can be seen as a result of degeneration, another popular eugenicist idea. Eugenics also rears its head with respect to Dracula’s Eastern European origins, which turn him into a menacing foreigner infecting upstanding British people.

Some other outdated science appears in the form of mesmerism. Van Helsing looks at Mina and makes hand motions in front of her, driving her into a trance to help locate Dracula. While these are now discredited scientific theories, at the time Stoker was writing, such ideas would have been in wide circulation.

Dracula’s heroes are also modern in ways beyond medical science. Jonathan Harker keeps a journal in shorthand, takes pictures of Dracula’s castle with his Kodak camera, and travels by train. Mina Harker is an assistant schoolmistress who employs a typewriter, organizes newspaper clippings, and sends telegrams; in short, she’s an example of a vibrant “New Woman.” Meanwhile, Dr. Seward uses a phonograph to record journal entries, availing himself of cutting-edge technology. Van Helsing is a lawyer as well as a doctor who believes he and his compatriots have “a power denied to the vampire kind; we have sources of science.”

All of these characters are a far cry from the scared peasants of Dracula’s homeland, and even from some of the previous protagonists of vampire fiction: Laura, who is the victim of the vampire Carmilla, feels old-fashioned next to Mina.

The setting of modern London also separates the book from other vampire narratives. As Stacey Abbott explains in Celluloid Vampires: Life After Death in the Modern World, while earlier Gothic literature “focused upon the past’s intrusion on the present . . . settings of old castles, monasteries, churches, and graveyards were no longer appropriate and were abandoned in favor of contemporary urban locations.”

Therefore, even though Dracula is associated with old Gothic fiction, it is very much a modern novel, embedded in a time when many scientific issues were hotly debated. If Dracula had been written today, perhaps it would feature CRISPR DNA sequencing; that is how modern Dracula feels in the context of its publication, and how noteworthy Stoker’s viral vampires were to readers of that era, who quickly embraced his vision.

The publication of Dracula cemented the vampire as both a seductive figure and a viral menace ripe with the possibility of infection, an idea that would echo for decades to come in both film and literature.

Although vampires had not themselves been viral, folklore and popular newspaper accounts did associate vampirism with disease. In the essay “Evidence for the Undead: The Role of Medical Investigation in the 18th-Century Vampire Epidemic,” Leo Ruickbie quotes a March 1732 edition of The Gentleman’s Magazine, which referred to “Vampyres” who “kill’d several Persons by sucking out all their Blood.” Ruickbie notes that in eighteenth-century Europe, readers were bombarded with tales of this kind. Numerous thinkers analyzed stories of the “chewing dead” and corpses that, as Calmet had indicated in 1746, “come back to earth, talk, walk, infest villages, ill use both men and beasts, suck the blood of their near relations.”

Some scholars have associated diseases such as tuberculosis with vampirism, positing that it might have served as inspiration for stories of the undead. The New England vampire panic, which began in 1793, is a good example of tuberculosis combining with the fear of the undead, leading to the exhumations of several corpses. One could say these stories went “viral” before the Internet, drawing the attention of numerous readers and priming them for Stoker’s tale.

*

Dracula uniquely positions disease in a new light. No longer is a vampire’s victim fated to die; instead they are doomed to be resurrected and infect others, festering a never-ending cycle of disease and breeding a vampire army. Dracula, after all, hopes to “create a new and ever-widening circle of semi-demons to batten on the helpless.” However, unlike zombies, who also transmit their infections via bites, Stoker’s vampires are perhaps even more dangerous because they retain those seductive qualities that their distant ancestor, Count Ruthven, typified: they are sexually attractive.

Therefore, when the vampire hunters track down Lucy after she has been vampirized, they find her dramatically altered: “Lucy Westenra, but yet how changed. The sweetness was turned to adamantine, heartless cruelty, and the purity to voluptuous wantonness.”

There is something “diabolically sweet” in Lucy’s voice, which makes Arthur open his arms as if to embrace the undead woman before Van Helsing springs forward with a golden crucifix and chases away the vampire.

The publication of Dracula therefore cemented the vampire as both a seductive figure and a viral menace ripe with the possibility of infection, an idea that would echo for decades to come in both film and literature.

There were some exceptions. Especially noteworthy is 1922’s Nosferatu, where a bald, rodent-toothed Count Orlok presents the vampire as something closer to the monster of old folklore. With the great influenza epidemic of 1918 only a few years behind, it is perhaps no surprise that this version explicitly links disease with vampires in the form of a plague of rats, but does not glamorize its villain.

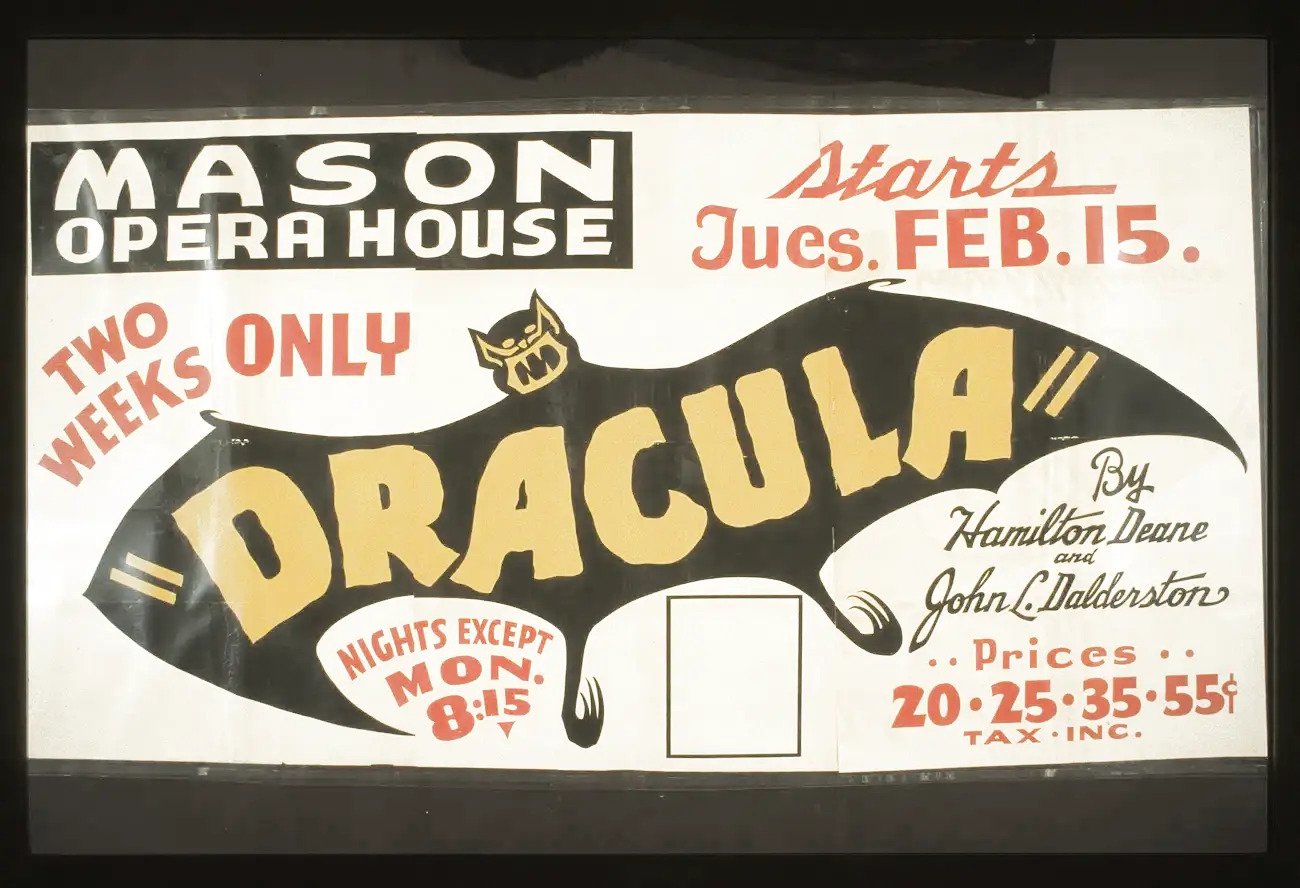

On the other hand, Tod Browning’s 1931 adaptation of the Dracula stage play, which was in turn based on the novel, went in a very different direction. The director cast Bela Lugosi, positioning him as suave, exotic, and sexy—the film was advertised as “The story of the strangest passion the world has ever known!”—and swathing him in an iconic cape and medallion ensemble that was imitated for years and years. In fact, the 1957 Mexican horror movie El Vampiro, released almost three decades later, has Germán Robles in that same costume, and when Christopher Lee makes his appearance in the Hammer film of 1958, he is still working in the mold set by Lugosi.

It is no wonder, then, that other movies and books continued to play with the same concept of viral vampires. One could even say that while some aspects of Dracula have been eliminated in its numerous adaptations—the transformation into a wolf, for example—others, such as vampirism as a viral infection, have become what we might call canon. That is, they have gone beyond defining just Dracula to becoming an essential element for all vampires.

There were works that attempted to differentiate themselves from the concept of the viral vampire. Martin, released in 1978, is interesting because it views its vampire as an entirely ordinary young man who may not be anything other than a disturbed murderer, a somewhat ironic take considering that director George Romero’s zombies echoed the viral vampire concept.

Nevertheless, vampirism as a transmissible disease continued to take root in the popular imagination. Novels such as Stephen King’s Salem’s Lot (1975), Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire (1976), and Kim Newman’s Anno Dracula (1992) all are rooted in viral vampirism.

It is easy to understand why Stoker’s vision of vampirism is so popular. Dracula’s viral elements are well suited to our tastes. For today’s readers, imagining vampires as people punished for their sins or babies born with cauls who are therefore fated to rise from the grave is likely a quaint or bizarre exercise. The viral vampire seems a much more acceptable creature.

Numerous films and TV shows have also added a touch of romance to the figure of Dracula, therefore evading the most gruesome and violent aspects of his viral vampirism. When Dracula attacks in the novel, it is not a seduction but something akin to a rape, a forcible transmission of disease.

As Dracula feeds Mina his blood, he holds “both Mrs. Harker’s hands, keeping them away with her arms at full tension; his right hand gripped her by the back of the neck, forcing her face down on his bosom. . . . The attitude of the two had a terrible resemblance to a child forcing a kitten’s nose into a saucer of milk to compel it to drink.”

Meanwhile, movies such as Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992) depict Mina and Dracula as star-crossed lovers, and the imbibing of blood in this film as voluntary, even romantic. Dracula’s direct adaptations, and the literary and movie grandchildren inspired by the vampire, therefore turn what might be a repulsive scenario (rape and infection) into an ideal courtship.

In fact, the sensuous appeal of the vampire emerges precisely because of that possibility of infection, a dynamic typified by works such as Stephenie Meyer’s novel Twilight (2005). Our contemporary, sexually appealing vampire may be technically transmitting a disease, but it is a disease that seems to the reader a gift: immortality. It is especially gratifying if the vampire can be “vegetarian” and only drink the blood of animals, as does Twilight’s Edward Cullen, or Angel of the TV show Buffy, therefore avoiding the thorny issue of murder. Furthermore, the vampire embodies many traits we find desirable (wealthy, good-looking, young, and prone to monogamy once it has met its special someone), rendering vampirism palatable.

It would be quite a different experience to be bitten and forcibly fed the blood of Count Orlok in a city stunned by the plague than to be turned into a powerful, immortal creature by a vampire with hard abs and perfect hair.

Therefore, the current viral vampire of pop culture often eludes the stigma and horror of previous monsters. But this was not so in Stoker’s time. After Mina’s attack she sees herself as “unclean,” and cannot touch or kiss her husband anymore, as though her vampirism could be transmitted in this way. Vampirism is a virus that must be feared.

Bram Stoker’s great-nephew Daniel Farson has theorized that the author died in 1912 of syphilis, in which case the association between sexuality and disease would make perfect sense. However, Farson’s theory, which first appeared in Steven Otfinoski’s biography Bram Stoker: The Man Who Wrote Dracula, remains a rather elusive diagnosis: there is little to indicate this was the case.

Nevertheless, Stoker, like many of his contemporaries, would have been aware of the disease and its effects. In our day and age, when many STDs can be cured with antibiotics, syphilis may not be so fearsome. Disease, in general, may not evoke the terror of days past, despite the existence of AIDS and antibiotic-resistant STDs.

But it is important to remember that in the context of Victorian England, viral vampires are horrifying precisely because they test the limits of science. Despite blood transfusions, despite proper medical treatment, Lucy perishes and then returns as a cannibalistic eater of children, only to be dispatched in gruesome fashion.

Dracula’s viral offspring cannot be understood using the same context of the more modern, romanticized incarnations of vampires. Instead, they must be seen as truly monstrous beings that prey in almost animalistic ways on the living, exhibiting the terrors of disease upon the body.

*

It is interesting to note that I am writing this introduction in the midst of a pandemic which has and will continue to redefine our thoughts about health, disease, science, and community, just as those were being tested in Stoker’s era. This will likely lead to new mutations in the long genealogy of the vampire. In fact, we might already be witnessing the birth of a new type of vampire.

Throughout the twentieth century, the most recognizable and popular vampires owed a strong debt to Dracula, and therefore usually featured European settings and characters. Even the more curious variations tended to telegraph their connection to the Count. The 1972 film Blacula, for example, features an African prince who has been turned into a vampire by none other than Dracula. The aristocratic background, a coffin as a resting place, even the costume used by William Marshall with a cape and a red lining—all recall the popular image of Dracula and the plots developed by Hammer Films.

One reason for this adherence to a certain mold is obvious: Count Dracula was a recognizable and exploitable property. Shifting too far from him and relocating the vampire from Europe was a risky endeavor, although studios did at times try to do just that: at one point, Hammer Films considered shooting a Dracula movie set in India titled The Unquenchable Thirst of Dracula. The script for it was adapted as a BBC radio play in 2017.

In films, therefore, Dracula, as well as his fellow vampires and most vampire hunters, remained tied to Europe and to whiteness. In the book world it was much the same, but several notable exceptions are worth mentioning.

The novel The Gilda Stories by Jewelle Gomez, published in 1991, stars a sympathetic Black vampire and her struggles through the decades. Fledgling by Octavia Butler, published in 2005, features a Black vampire who has the appearance of a small child and is much more of a science fiction piece than a traditional Gothic novel. On the large screen, Cronos, a 1992 film by Guillermo del Toro, placed its vampirized senior citizen in Mexico City and eschewed connections to traditional vampire mythology, while the 2009 Korean film Thirst gave us a gentle priest who becomes blood-thirsty after a failed medical experiment.

The success of Twilight should have spawned more vampiric variations, and perhaps more diverse vampires, but instead it seemed to create a boom-and-bust cycle so that by the time I was working on a vampire novel in the early 2010s, few publishers would consider it. Certain Dark Things was eventually published in 2015, quickly went out of print, and was reissued in 2021. It lacks European castles and misty moors, instead taking place in a noir-tinted alternate Mexico City where a vampire is on the run from a rival narco clan.

Although vampires still seem to be in something of a down period (at least according to editors), there have been some interesting entries in the past few years. These include the 2017 novel A Small Charred Face by Kazuki Sakuraba, which is a sharp departure from what we might call a traditional vampire narrative, as well as Alexis Henderson’s 2022 novel House of Hunger, part of the new crop of Gothic titles that seem to be gathering steam with readers.

On a more personal level, in 2021 I arranged for the first English-language translation of The Route of Ice and Salt, a novella by Mexican writer José Luis Zárate, which was originally penned in the 1990s. It focuses on the captain of the Demeter, the ship ferrying Dracula to England, as he discovers that something sinister haunts his crew. It is an erotic, queer tale of horror and desire. David Bowles translated the text from the Spanish, helping me realize a lifelong dream of bringing this novella to English-language readers. Curiously enough, Dracula was also the subject of another Mexican writer’s work when Carlos Fuentes published Vlad in 2010, which has the Count moving to Mexico City.

The dead travel fast and sometimes they travel far. All of these books and films show the possibilities inherent in vampire narratives. Whether we might witness more viral vampires, an increase in non-European settings and characters, or perhaps even a return to the folkloric vampire as a blood-engorged corpse wrapped in a shroud, I cannot say. Nevertheless, the vampire, as well as its most emblematic incarnation in the form of Dracula, will continue to haunt us and his descendants.

__________________________________

Bram Stoker’s Dracula, with introductions by Silvia Moreno-Garcia and Alexander Chee, and illustrations by Kaitlin Chan, is available from Restless Books.

Silvia Moreno-Garcia

Silvia Moreno-Garcia is the author of The Daughter of Doctor Moreau, Velvet Was the Night, Mexican Gothic, Gods of Jade and Shadow, and many other books. She has won the Locus and British Fantasy awards for her work as a novelist, and the World Fantasy Award as an editor.