Seven Novels That Explore Friendship In All Its Messy, Complex Beauty

Jeremy Gordon Recommends Yukio Mishima, Elena Ferrante, Daniel Clowes, and More

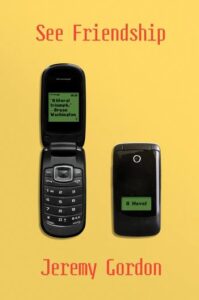

The title of my novel, See Friendship, comes from a somewhat underpromoted Facebook feature that allows you to “see” the entirety of your shared history with a friend: your mutually exchanged posts, statuses, photos, etc.. While I’m sure its developers intended to elicit some quick and easy nostalgic reaction by allowing you to skim from past-to-present, I’ve always found something distancing, if not upsetting, about these contextless interactions.

In front of me is hard evidence that I posted “whaddup tho?” to my buddy Ryan’s wall in the summer of 2009—but what prompted this fraternal gesture? Why didn’t Ryan reply to me? When is the last time I talked to Ryan? Is he still alive? Yellowing photographs and aged letters denote the passage of time, but a Facebook comment appears eternally fresh—that crisp black text against stark white background—as though 16 years have not elapsed between then and now.

In some sense, the feature is nostalgia-ruining. I’d certainly like to imagine that Ryan and I were blood brothers with a singular dynamic, his erudite charm perfectly twinned with my earnest go-getterism, but then here’s proof of how we really talked: “whaddup tho?” Friendship is better as a Rashomon-style recollection of two separate experiences, each person deeply attuned to the contrast in demeanor, deportment, and general disposition that make one person Batman and one person Robin, or one person Batman and one person Superman, or maybe they’re both Batman.

But something is always lost, when attempting to recall your life from the present. When I was writing See Friendship, I thought of my warm and idealistic friendships, where my buddy and I have always been on the same page and nothing could ever change that—and then I remembered the friendships where there’s no misrepresenting how it really was, as much as I might prefer to lie to myself.

*

Yukio Mishima, Spring Snow

Every close friendship is a study in contrasts: one person is more like this, the other person is more like that, and each man may learn much about themselves by pondering the difference in behavior. I have been the reasonable teetotaler in some friendships, the person more likely to say “I don’t know about that”—and in others I’ve been the devil-may-care troublemaker, eager to poke at my more pragmatic pal’s reservations. It all depends, really. It’s not that my personality is chameleonic, but this is how you expand the possible parameters of how you might be: by witnessing how someone else does it.

Spring Snow is a prime exemplar of one of my favorite dynamics: the friend who is normal and the friend who is crazy. The friend who is prudent and cautious, and the friend who does everything on gut feeling. Kiyoaki Matsugae, the novel’s “protagonist,” is a beautiful, passionate, and vain scion of an aristocratic family; his best friend, Shigekuni Honda, is studious, diligent, and responsible. Yet this is not jock and the dork, but a friendship of individuals, each confident in their own personhood and totally fine standing somewhat apart. Honda is not jealous of his friend’s tempestuous entitlement—by observing Kiyoaki, he better understands his own personality, and more confidently behaves as himself.

Elena Ferrante, Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay

A friendship of contrasts can also create an ongoing deference, as one friend is secretly jealous of how the other walks through life, yet can never quite assert herself. I read the Neapolitan novels in the same year as I read Spring Snow, and while the Lila/Lenu relationship seemed to mirror Kiyoaki and Honda, Lenu spends much of her life afraid of, and in competition with, the more casually delightful Lila. Of course, projecting your own insecurities onto another party only bears so much truth, and this is the irony of the first installment’s title: to each other, they’re both the brilliant friend. In Lenu’s eyes, Lila is someone who can effortlessly commandeer everything that Lenu wants for herself.

As we follow their lives, I like the surprising and transgressive moment in the third novel when Lenu finally behaves irresponsibly, leaving her family in order to carry out a doomed affair with Nino. In this moment, she is living the role of her chaotic friend, but for the wrong reasons—she is still herself, and throwing caution to the wind is not going to work out as well as it does for Lila (and it doesn’t always work out for Lila, either). But you understand Lenu, in the moment. After a lifetime of responsibility, why not behave badly? Why not play the wild one?

Magda Szabo, The Door

When I picked this book as a possible choice for this list, my wife asked me: “Are they friends, though?” This is a great question. As Magda, the narrator, notes of her longstanding relationship with her housekeeper Emerence, “relations with her were at their most harmonious when one of us was in some sort of difficulty.” Yet because their friendship develops in older age, Magda and Emerence have skipped past the nostril-flaring suspicion that characterizes some younger people; they have each lived their own lives, and come to each other as fully formed adults who can speak to each other more plainly.

I’m much younger than both of these women, but I’ve noticed how the friendships I make now, opposed to the friendships I made then, are more immediately honest; I am less eager to impress, or deflect from how I really am, because I know my principles and beliefs have counted for something in my life. Which makes Magda’s eventual betrayal, if you want to call it that, so devastating: She acts out what seems like the best course of action (and may be, by any objective standard) but Emerence is so incapable of seeing it like this that the friendship is ruined, permanently, bringing no sentimental denouement or bittersweet rapprochement.

Herve Guilbert, To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life

The title of Guilbert’s autofictional novel is, to me, a wry provocation—it’s so dramatic, yet it’s also the truth. Guilbert really was let down by a friend, named “Bill” in these pages, who promised he could get Guilbert into a test group for a new AIDS medication, only to disappoint, and this failure presaged Guilbert’s eventual death. This is another tension of friendship: What matters deeply to one cannot matter as much to another, and while Bill surely “cared” about his friend, did he do all he could?

Meanwhile, Guilbert details the moods of those in his milieu who are also suffering from the same illness. “That was probably the hardest thing to bear in this new era of misfortune that waited us,” he writes, “to feel one’s friend, one’s brother, so broken by what was happening to him—that was physically revolting.” The disease brings him closer to some, and pushes him further away from others—and in death, the title is somewhat of a middle finger to a friend whose empathy had a natural limit. Words alone cannot capture the clear-eyed desperation of Guilbert’s writing in this novel, as he and his ailing friends approach the veil.

Roberto Bolaño, The Savage Detectives

One cannot be too critical of “the scene”; it’s just unbecoming. While it may produce a sense of FOMO to see groups of young, beautiful, and potentially talented people palling about together, the arts are so culturally diminished across global society that you can’t fault any group of like-minded individuals for falling in with each other. Proximity to minor success is no guarantee of lasting value, anyway, and what seems like the most important thing at the start of The Savage Detectives—the mid-70s Latin American experimental poetry scene—quickly becomes irrelevant as the years go on. Bolaño is unsentimental about what happens to the writers of this world: some die, some disappear, some quit, some sputter out. Nobody becomes famous, nobody produces work of evergreen merit.

But the flip side is that Bolaño was fictionalizing the real poets of his mid-70s Latin American experimental poetry scene, essentially immortalizing them all as charming failures in a novel that now regularly makes its way onto “best ever” lists. I have never read a poem by Vera or Mara Larrosa, but their fictional analogues, the Font sisters, are etched in my memory forever—and if literature may be considered as an act of preservation, I do find it kind of beautiful and meaningful that Bolaño froze his friends on the page and turned them into minor legends. Sorry to be a little sentimental about it.

Mary Gaitskill, Veronica

One of the key relationships in Kenneth Lonergan’s Margaret is the friendship between Lisa (a young woman played by Anna Paquin) and Emily (an older woman played by Jeannie Berlin), who befriend each other after Emily’s best friend is struck and killed in a bus accident that Lisa happens to witness. It’s been a while since I’ve seen the movie, so I can only paraphrase the texture of the interaction, but one of my favorite moments is when Emily accuses Lisa of milking the tragedy to add color and drama to her own existence: “We are not all supporting characters to the drama of your amazing life,” she says. Everything feels so intense in youth, but age brings the perspective requires to get along with all this intensity—and this contrast between young and old also marks Veronica, in which a former model reminisces about her friendship with the title character, whose impact and worth cannot quite be appreciated until the narrator is old herself.

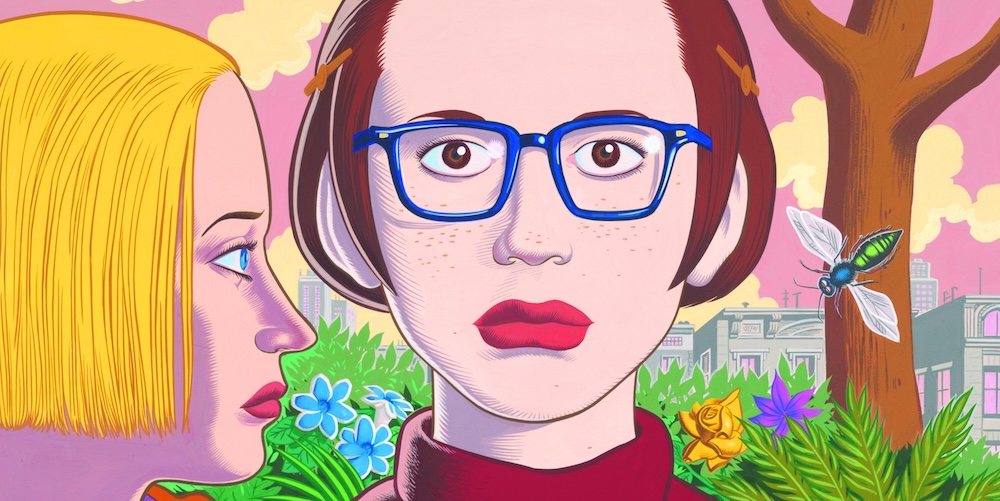

Daniel Clowes, Ghost World

The teenage delinquents of Harmony Korine’s Kids are total nihilists—they have no future, and are content to burn out in an explosion of drugs and sex. But the teenage delinquents of Daniel Clowes’s Ghost World don’t actually want to live out their death wish with such intensity; though they do not seem to have a place in society, they have not given up on the future. The price for figuring out what comes next is their closeness—once besties, Enid and Rebecca slowly grow apart over the course of Clowes’s graphic novel, as they approach adulthood in their own way.

I think there is something resonant and true about this; entering “the real world” requires shedding a former self, and sometimes people are first to go in that transition. One day, Enid and Rebecca will think of each other and find it impossible that they were ever so intimate. But, to quote the ongoing mantra of those who cannot find something more poignant to say about a heartbreakingly banal turn of events—because whose life is not studded with people that once meant so much?—it is what it is.

__________________________________

See Friendship by Jeremy Gordon is available from Harper Perennial, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Jeremy Gordon

Jeremy Gordon's writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Nation, Pitchfork, The Atlantic, and GQ. He was born in Chicago, and currently lives in Brooklyn with his wife, Jen. See Friendship is his first novel.