I’ve never felt as alive as I did that summer. Alive, needed, run off my feet. Every evening we were queued out the door, we had bookings a year in advance. It was the kind of place people of a certain age called hip, while the rest of us rolled our eyes, discreetly, not wanting to jeopardize our tips.

Back then, when the country still thought it was rich, there was always some brash, impossible customer demanding a table from the hostess just as the dinner rush took hold. These arguments added to the atmosphere, the heat, the energy that ripped around the establishment and kept us going six out of seven nights a week.

The restaurant, let’s call it T, was in a large, ivy-covered building two streets over from the Dáil. We served businessmen, politicians, lobbyists, the type of men who liked a side order of banter with their steak and old world red. We learnt quickly to talk nonsense about the property market and the boom, though we didn’t really have a clue, we just knew that the wages were decent, the customers wore suits, and the tips were sometimes obscene.

We only employ college students.

Don’t be brainless.

Don’t be nosy.

Be tactful.

Be knowledgeable.

Your Châteauneuf from your Côtes du Rhône.

Your bouillon from your bouillabaisse.

Your? As if. We got the same pasta tray-bake and soggy salad every day before service. It was delicious—it was free.

I remember the heat of the kitchens, the huge flat pans with slabs of butter sizzling from midday, though I was fortunate to mostly work dinner, when the bigger tables came in. You’ll get cocktails and evenings for sure, Flynn the bartender told me with a homicidal grin, then he muttered some quip that ended in ass to his sniggering colleague. That was the Ireland of the day, asses replacing bottoms, cocktails replacing pints, quick deals and easy money, opportunities that had taken decades—centuries—to filter down.

The kitchens were so hot that summer you could feel the burn on your blouse in the throughway, the small space off the main dining room that joined front of house with back. This was the nucleus of the restaurant, where we fired orders on computers, gossiped about customers and complained about the bar staff who’d let our drink orders back up while busy working their own tips. Double doors would flap open to the kitchens as a runner passed through with four plates—the maximum number permitted—and the heat would come at us in short, magnificent bursts that were often accompanied by shouts from the chefs, which would remind us who was really in charge and send us running once more onto the floor. Yes, sir, No, sir, may I tell you, sir. It was like a show. It had the buzz of live performance.

The customers were a who’s-who of boomtime Dublin, the men in suits and open-necked shirts, the women in stiff dresses and blow-dries. With our clipped ponytails and rubber-soled pumps, we could not compare. And yet, we did not go unnoticed.

Some of the restaurant staff were famous themselves. Everyone knew the manager Christopher, his high-boned London face, and the easy charm that was just the right side of fawning. Christopher-call-me-Chris, who was lovely to work for, clear and very funny, unless you were obviously hungover or in the habit of being late. Unless you offended a customer. It was the number one rule in the restaurant, in every good restaurant around the world: the customer is always right.

They came to T for the atmosphere, and for the cooking, certainly, though they never saw the reality behind the double doors, vaunted men in white with unnatural concentration, hot faces and drenched hairlines when they took off their caps at the end of the shift. The only women in the kitchen were the Polish dishwashers who doubled as baristas when the bar was mobbed and who refused to speak English to the waiters they disliked.

Most of the customers came for the head chef Daniel Costello, who was so good at cooking that he didn’t need stars (though shortly after I left he got his first, which nearly killed me). He had two sous chefs who hated each other but stuck it out to work with him, then the rest of the team—nine or ten men, largely in their twenties—who each had their own station along the stainless steel counters that ran the length of the kitchen. They prepped and cooked, shouted and swore. They plated dainty meals in a matter of seconds. They listened to classic hits on the radio, or played loud music on the prehistoric stereo above the sinks. They drank vats of Coke from plastic cups with ice that melted in minutes. One of us waiters would do a refill round whenever we caught a lull. We looked after them and they looked after us. That was the theory. But really we stayed out of their way, and out of the kitchen unless we were buzzed. Theirs was a different world. You could smell it the moment you went back there, through the spices and sauces and the bins full of leftovers. Talent and testosterone. You hadn’t a chance. You were a minnow in a pond—a help, a hindrance, a nothing.

The serving staff were at the end of the chain, attractive bartenders and waiters hired to make the customers feel good about themselves so they’d spend more money. Easy on the eye. That was the phrase used by the owners, a consortium of rich men who treated the restaurant like a fancy canteen where they came and went as they pleased. Easy on the eye. It was literally part of the advertising policy. Everyone in the industry knew—you didn’t apply unless you had a certain figure or face. They’d turned away a waitress in her thirties, one with years of Michelin experience. They told her she wouldn’t be able to keep pace. Not in this restaurant, this so-hot-right-now restaurant.

So I suppose it is fair to say that when I went for the job, I had an idea that I was not uneasy on the eye. But it wasn’t something I thought about all that much. And then after that summer, when I no longer worked there, which is to say when I was fired, I did not want to think about it at all.

Even before I got the job, I knew that T would be a fun place to work. There were rumours about town. A generosity with shift drinks, a runner who doubled as a dealer, people having sex in the bathrooms, the odd private party with DJ such-and-such. We all thought it was exciting. For Ireland, we thought it was insane.

My interview took place in the middle of the restaurant, at Table Four as I would later learn, and lasted around ten minutes. While two middle-aged men scanned my CV and body—it was as blatant as those machines at the airport—I watched waitresses fold napkins at the bar. A stocky bartender was teasing a girl who looked younger than me, pretending to knock over her pile of cloth triangles with his tattooed arm. The messing broke off suddenly when Daniel Costello himself approached with a bowl of chips and some dip they all appeared to love. I found it hard not to follow his movements, that uncanniness of seeing a celebrity in real life. He was tall, almost hulkish, with formidable arms and unruly hair. The air in the room seemed thinner with him in it, the low roof gave a little bounce.

On the way back, he stopped at our table and I avoided his eyes, dark and roving, and not particularly interested in me. I stared at the immaculately white, double-breasted coat, the grandfather collar neat at his neck, which was tanned and thick. ‘Ever more canaries,’ he said to the owners. They laughed, then considered me in silence for a moment. I felt like I might melt. ‘Take it easy on her,’ Daniel said, walking away.

After a few cursory questions (Tipperary, twenty-one, business studies), one of the owners offered me the job on the spot and I said yes without asking about the pay, which caused the other one to laugh and hit the table with his hand and promise to teach me a thing or two about the real world.

I started the following Tuesday on a trail shift, shadowing a real waiter, helping with whatever small tasks they might entrust to a newbie. For five hours, I ran after Tracy, a slim, sharp-tongued redhead from Drogheda. I didn’t leave her side all night. It was tricky work, trying to make a note of everything she did, without distracting her tables. From the beginning I loved it, the sense of belonging the uniform gave me, the snug blouse and tailored skirt, the neat black aprons we tied around our waists, buzzers clipped on the back.

I felt privileged to work in a place that was so obviously luxurious. People, I mean ordinary people, came to the restaurant once or twice a year for special occasions, whereas I was lucky enough to be there six nights a week. The place was so fancy it almost seemed holy. This was back when restaurants made an effort, when bare bulbs and exposed brickwork were only seen by the builders. Everything was plush and radiant. Stained-glass windows in the bathrooms, velvet-roped elitism for the upper floors. Customers were always commenting on the varnished floor in reception, the shine, the remarkable cherry wood. I learnt to tell them it was antique, over a hundred years old, part of the original building, a former merchant bank, which meant that they were not just having dinner but dining out on history.

In the main room that stretched over two levels, ground and mezzanine, there was soft grey carpet, beautiful to look at and a nightmare for carrying cocktails. The walls were a lighter shade of grey and had original paintings by Irish artists I’d never heard of—Nano Reid, Robert Ballagh, a huge canvas of blocky autumnal colours by Sean Scully, which everyone said was a masterpiece. I knew nothing about art. Though I’d spent three years at college in Dublin, at heart I was still from Thurles, a midlands town whose only museum was a glorified tourist centre that told a fine story about the Famine. I used to eavesdrop on the customers’ conversation. I liked to hear the different reactions from the rich business types who seemed to view art as a challenge. We have a Scully in the veranda, they might say. I found a stunning Le Brocquy at auction. You could always predict what people like that would order—some part of a cow and a bottle with Grand in the title. The kind of customer who cared about the origins of the produce, but didn’t give a damn about the staff.

The walnut bar was another talking point, glasses and bottles backlit in cool pink, a vast tinted mirror that gave an illusory depth to the room. On the upper floors, there were smaller spaces, similar in style to the dining room, grey carpets, linen cloths, banquet seating for the tables near the wall. I loved the way the rooms changed as the restaurant filled, the afternoon slid into evening, the low hum of prep that would gradually give way until you were right in the centre of it—in the weeds, we called it—and the noise and rush was incredible.

Service!

Behind you!

Coming through!

Fire seven!

Clear two!

Turn ten!

Every day, in the break between lunch and dinner, we had a team meeting. Half four sharp, front and back of house, all the waitstaff standing to attention. Depending on Daniel’s mood, it could be a wine-tasting, a specials run-through, a fierce interrogation about various items on the menu. Which of the starters contain nuts? How many oysters in the seafood platter? What’s the difference between a langoustine and a prawn? Between jus and velouté? An artichoke and a chayote? Answer, a pass or a bollicking.

For the initial meetings as a lowly backwaiter I stayed under the radar, but by Saturday afternoon of my second week, I no longer felt secure. Lunch service had been chaotic. Tables were slow to finish, the ticket machine jammed, a bottle of Montepulciano smashed on the bar. Daniel ranted, looked everyone in the eye as he spoke, seeking out ignorance. The waiters aren’t selling, he said. A T-bone. A fine cut. A treat. What was wrong with us? He glared our way and only Mel, the elegant head waitress, held his gaze with her clear, expressive eyes.

‘It’s too big,’ she said, when he’d worn himself out.

Daniel turned to face her. He was in a polo shirt, muscular forearms crossed over each other. His fist clenched as Mel continued, the skin tightening at his bicep.

‘No one wants a sixteen ounce steak,’ she said. ‘You’d be better off doing it for two.’

‘Are you a chef now?’ Daniel said. ‘Will we put her in whites, Christopher?’ And then to the gallery, his underlings who were huddled by the archway to the throughway, ready to run back to their prep, to the real business of the restaurant, ‘She’d look good in white, wouldn’t she, fellas?’

There was some mild hooting that died out quickly as Mel eyeballed them.

‘Whatever, Daniel,’ she said. ‘It’s up to you. But you’re right—it’s not selling. Not even to that table of bankers. They all went for the fillet.’

‘Well,’ Christopher said, ‘we could slash the price.’

‘No fucking way!’ said Daniel. ‘Are you mad? That cut. That beautiful piece.’ His eyes flashed again. His melty-brown eyes, as Tracy had called them the previous night, four or five wines in. With another waitress, Eve, we’d gone drinking after the shift to some dive on Montague Lane that had a back-door policy for industry workers. I’d woken up dying right before work, hadn’t even had time to shower.

Christopher raised his palms.

‘Just sell, girls,’ Daniel said, with mild asperity. ‘Sell like your job depends on it.’

‘How many to shift?’ said Christopher.

‘Eight. And they need to go tonight. OK?’ Daniel tipped his head respectfully at Mel.

She nodded and we followed suit.

Daniel turned to the chalkboard to go through the rest of the specials. He was saying something about depth and sauce and milkfed veal, when my legs started to shake. All I wanted was a seat, the comfort of the staff meal that followed team meetings—the creamy pasta sauce, the salt.

‘You,’ Daniel said. ‘Sell me the veal.’

It took me more than a moment to realize that I was the unfortunate ‘you’. I looked at the carpet, hoping he’d move on. I wasn’t even a waitress yet. I couldn’t sell to anyone.

‘You!’ His hands were waving in the air.

I felt a swell of vomit between my ribs.

‘Veal,’ I said uselessly.

‘And?’

Everyone was watching. Christopher didn’t seem remotely like he might save me. Tracy shrugged and examined her nails.

‘The depth,’ I said. ‘In the sauce.’

‘What in the fucking fuck?’ Daniel exploded, a long line of expletives that were impressive in their own right, but not when they were firing like pellets towards your face.

‘All right, Daniel, we get it. All right.’ Mel moved in front of me.

Daniel stormed off to the kitchen, his crew trailing after him.

‘Thanks,’ I said to Mel. ‘Thank you.’

She shook her head and pointed to the bathroom. ‘Clean yourself up,’ she said.

*

There were fun times in that restaurant—it isn’t fair to pretend otherwise now—and there were plenty of good people.

Mel, my saviour, with her knowing eyes and long black hair. For reasons I couldn’t quite grasp, she had huge sway with Christopher-Chris, freedom to say what she pleased. It seemed to go beyond her seniority, a cryptic code between them that she occasionally deployed to defuse the stresses and tense exchanges of service.

Rashini the hostess, a former model from Sri Lanka who spoke four languages and never stopped smiling. She was making her way through some list of classic novels, which she used to hide in the gilded stand in reception, until a customer shouted at her one night, when she was slow to get his coat, that if he wanted a librarian he’d go to the damn—he was so drunk, he didn’t finish the sentence.

Vincent the sarcastic sommelier, who hated the expression team meeting, because it was business jargon and we should call it what it really was, a daily dressing-down in front of everyone for the previous evening’s mistakes.

There was Jack, my favourite bartender, a Corkman who always had the drinks ready on time, who handled our incredibly urgent demands with droll humour and phlegmatic grace. He told lame jokes in a sing-song voice and flirted outrageously with the older female customers, though he was terrifically and emphatically gay.

Thiago, the Brazilian bar-back who’d moved from São Paulo to Gort, then from Gort to Dublin when his girlfriend had twins. They gave them Irish names so that they’d fit in with their future schoolmates, and no one had the heart to tell him that this was 2007, that Máire and Gráinne would probably not thank him when they grew up in a swarm of Chloes, Nicoles and Isabelles.

Tracy and Eve, Trinity students like me, all of us about to go into fourth year, similarly dazzled by the garish adult world of the restaurant. We were a cohort. Blow-ins. Tracy from Drogheda, Eve from Galway. We paid rigorous attention in team meetings, nodding along to dishes and drinks we’d never heard of, before escaping to the alley beside the restaurant to chain-smoke Marlboro Lights and look up words like beluga and tempranillo on Eve’s fancy phone. Nearly all the restaurant staff smoked, even the people who thought they didn’t. A cigarette was like a magic rod absorbing the tensions of a shift, a break from the madness and the heat.

And there was Daniel, of course, we all loved Daniel. The skill, the swagger, the hair, even the naff red bandana that he sometimes wore during prep. We were in awe of him, of the fact that he didn’t seem to care about anything except the food. Serious cooking and good times, that was the dream we sold at T, over and over again.

Three to dress!

Service!

Fire the mains!

Daniel was a human exclamation mark.

Service!

Probe!

Fifty-fucking-eight!

A conveyor belt of curse words.

Fuckwit!

Service!

Wench!

Fucking wench!

The word fuck was said so many times over the course of each service that it was almost devoid of meaning. (See also: sorry, sweetheart, heat of the moment). It was his kitchen. He could say or do just about anything, though I don’t think I fully understood this until the end.

On week nights the service would start early, older couples and culture heads for the pre-theatre menus, which ended at half six sharp and not six thirty-four, as we all discovered the evening Daniel threw a plate of sautéed spinach at Eve’s head. (She ducked in time—quick reflexes are an industry must.) The tables would peter out around half nine or ten, with Christopher a godsend in this regard, gently dropping a bill as he enquired about their welfare, using the authority we lacked to boot them out the door, saving our tips in the process.

Weekends were the opposite, a lull for the early hours—the odd table of two, a late lunch nursing their coffees and drinks—and then so many people arriving at once that you wouldn’t look at your watch for hours.

One trick was to stagger them, each table a little later than the last, so that no one needed you at the same time, but this never worked out in practice—people need things all of the time, and it was our job to say yes without question. I learnt quickly that having them on the same courses worked best. Fewer trips to the kitchen, to the computer, even to the bar if you’d mastered the trays. I had a steady hand and good balance. I never spilled a drink in my time there, not even those fiddly sunset-coloured cocktails. At the weekends, the drinks flowed and the food came fast from the kitchen, plate after plate, like a ballet when it worked well. Five adrenalin-filled hours and when it was over, you counted your tips and divvied your tip-outs, a chunky twenty per cent split between runners, dishwashers and bartenders. You went to the alley for a much needed cigarette, then you sat at the bar with your heels out of your pumps and knocked back your shift drink like it was water.

Our only day off was Monday, when the restaurant closed. Lights out, teal blue shutters down, which usually meant a session after work on Sundays. Pilfering house spirits until Christopher kicked us out, heading to the dive on Montague Lane, drinking and dancing into the early hours, scoring inebriated men whose names we’d forget by morning. Blurry memories of sausage rolls and Lucozade and long, light-filled afternoons sprawled across the couch in my student digs in Islandbridge. My flatmates would come home from their summer internships and find me in pyjamas watching the repeat episode of Neighbours, able to quote lines verbatim for their amusement.

No matter how mad the weekend had been, we were always ready for a new week come Tuesday. That was the best thing about the restaurant. You could reset your tables, your tips, your mistakes. You could reset the splotch of marinara sauce on your blouse. You could reset the blisters on your feet. You could reset your life. Everything that happened the previous week was over. Nobody remembered anything. It was just too busy, there was too much going on.

__________________________________

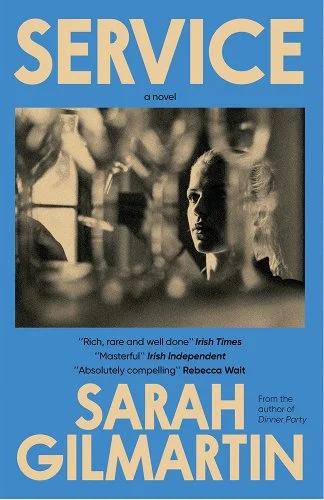

From Service by Sarah Gilmartin. Used with permission of the publisher, Pushkin Press. Copyright © 2024 by Sarah Gilmartin.