Secrets and Lies in the Early Days of the Klondike Gold Rush

Brian Castner on Lying George Carmack and the

Discovery of a Lifetime

For many years to follow, Lying George Carmack, who was famous up and down the Yukon valley for his many tall tales, told the story of the Klondike discovery this way:

In August 1896, when he and Skookum Jim and Charlie left Robert Henderson—who had just opened the first small claim in the Klondike watershed, at a place he called Gold Bottom—they followed the ridgeline west, off the Dome and back toward Rabbit Creek. It was slow going, a swamp of grass tussocks and half-frozen muck, sinking to their thighs in glacial ooze as they swatted mosquitoes. These were the murky headwaters of a series of creeks that fed the Klondike, and upon following one feeder stream, Carmack began to find pools of black sand that glinted in the sunlight. He led them down this creek, where they came to a major fork and then worked their way lower again. Carmack was in charge and ahead of Jim and Charlie, his head down like a bloodhound following a trail, when suddenly through the clear cold water he saw bare bedrock and a knowing flash.

“Look down there, boys,” Carmack called. “If this creek is good for anything at all, we surely ought to find gold down there.”

Mixed in with the sand and gravel were gold flakes like grained wood shavings, and oblong and irregular lumps that had the look of something molten and cooled. Carmack dropped his pack, rubbed his misty eyes, leaned over, and picked up a gold nugget the size of a dime. There was so much gold layered between the slabs of bedrock, he thought they looked like cheese sandwiches.

Carmack figured they had somehow made it to an upper section of Rabbit Creek, one they hadn’t explored before. He and Jim and Charlie moved up and down the stream, panning for the densest concentration of gold. They camped several days along that creek, and when he was satisfied they had found the best place, Carmack took a hatchet and chopped a blaze in a spruce tree and wrote this with a pencil in the exposed heartwood:

“TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN: I do, this day, locate and claim, by right of discovery, five hundred feet, running upstream from this notice. Located this 17th day of August, 1896. G.W. Carmack.”

Carmack then pulled out a rope, measured five hundred feet up the creek, and set another stake to mark his claim. Then he repeated the process, marking the section known as One Above discovery, which would be for Jim. Then Carmack did the same downstream of his original marker, One Below for himself again—as the discoverer, he was allowed two claims—and then Two Below for Charlie. Two thousand feet in all, of what Carmack had decided to call Bonanza Creek.

There was so much gold layered between the slabs of bedrock, he thought they looked like cheese sandwiches.

Carmack told Skookum Jim to stay and guard the claim, as he and Charlie would go to Fortymile right away and file the legal paperwork. But as they made their way down to the Klondike River, they saw four white men coming up the ridge: McGilvray, McKay, Edwards, and Waugh, all experienced prospectors.

“Where do you think you’re bound for?” Carmack asked.

“Well, we’ve just come down from upriver and heard at Ogilvie that a prospect has been found,” said one of the men. They had obviously been sent by Joe Ladue to meet up with Henderson at Gold Bottom. “Do you know anything about it?”

“Yes, I left there three days ago.”

“What do you think about it?” one asked.

“Well,” Carmack said, and paused, drawing it out. In later years, he always liked telling this part of his story best. “I don’t like to be a knocker, but I don’t think much of it, and I wouldn’t advise you to go up there.”

The faces of the four men dropped in disappointment, until Carmack continued.

“I’ve got something better for you,” he said, and showed them his handful of gold nuggets.

So ends Carmack’s version of the tale.

And that was how the miners’ code was broken. Henderson’s reprisal, Carmack’s spite. Not only did Carmack never tell Henderson about the strike, he stopped anyone else from telling Henderson until it was far too late.

*

When Carmack strode into the saloon in Fortymile three days later, on August 20, 1896, he did so with a conceited air about him, the like of which was wholly out of character and, the assembled miners agreed, unbecoming as well.

Carmack’s uppity tone did not seem to match his environs. Fortymile was a dreary collection of whiskey dens and moldering log cabins tossed about with no order or reason. Trash filled the streets, starving dogs ran rampant, and the dance hall generously known as the “opera house” was a place where the only singing consisted of barroom chants, and the only dancing partners to be had were Indians nursing infants on the tit or sporting girls turning tricks.

But Fortymile was also a place that provided every kind of service a miner could need, from blacksmiths to outfitters to druggists to barbers. And on the day Carmack arrived, the saloon was full, as miners had returned to town to gather their supplies for the coming winter. In town was Big Alex MacDonald, a land purchaser for the Alaska Commercial Company, who was also called the Big Moose for his enormous bulk, big lips, and sloping forehead. Also Swiftwater Bill, so named because he preferred to walk around rapids rather than run his boat through. Cannibal Ike, who liked to eat his kills raw. Howard Hamilton spent the winter chipping away the wood from the inside walls of his cabin; he said the thinned two-inch logs let in more light. Plus Crooked-Leg Louie, Slobbery Tom, and Pete the Pig, crazy old codgers all. Robert Henderson had never spent enough time with any of the men to earn a sobriquet; the other miners just called him Bob.

Carmack’s name, on the other hand, was well known. Lying George.

The only man missing was the saloon’s owner, Bill McPhee, who was temporarily all the way up in Circle City, many days’ journey to the north. In his place, a bull-shaped young man named Clarence Jesse Berry was tending bar. New to the district, he had also earned no nickname as yet, and merely went by C.J. Like all Berry men, Clarence was bald, with a broad shiny cupola of a forehead and square foundational jaw, silhouette of a cathedral. He was a reluctant barkeep, but having just returned from a five-week failed prospecting trip, he needed the steady pay.

In this, Berry was typical. As a general rule, the men of Fortymile— some six hundred of them, mostly American—made only bare wages on their claims, just enough to keep them in the country another season, enough to order a drink at Bill McPhee’s saloon but not enough to stay reliably drunk.

And so these sober-minded prospectors were suspicious of Carmack, as their common impression of him was less than compl mentary. When Carmack strutted in, one miner turned to him and called out. “Hello there, you damned old meat-eating Siwash, how’s fishing? Got any dried salmon to sell?”

The room laughed, for while they all would gladly eat Carmack’s grub, they knew that even the unluckiest prospector was more reputable than a fishing Indian-lover like Siwash George.

“Boys, I’ve got some news to tell you,” Carmack said. “There’s a big strike up the river.”

The men in the saloon were not interested in such talk, barely pausing their billiard games to scoff. They had heard all of Joe Ladue’s confidence schemes already, and anyway, no one would believe that Carmack knew anything about prospecting.

So they mocked him again, laughed at Lying George, until he reached into his pocket and pulled out a brass cylinder the size of his little finger. It was one of Skookum Jim’s Winchester cartridges, corked with a stick. Carmack removed the plug and poured out a small pile of gold sinker nuggets onto the bar.

“Well, how does that look to you, eh?” said Carmack.

“Is that some Miller Creek gold Ladue gave you?” the first man said, and everyone laughed again, but not as hearty and rough as before.

They all examined the nuggets. Every creek hosted its own particular combination of rock and water, and so ground gold according to its own unique signature that any miner with time in the country could read like handwriting. The prospectors crowded around to look.

This was not Miller Creek gold. This was gold of a shape and cast as they had never seen before.

It really was a new strike. A liar had just announced the truth. “$2.50 to the pan,” Carmack said. Two dollars and fifty cents was an almost insane boast, twenty times what any man would call a rich prospect. And none of them would have believed it, except there was Carmack, of all men, holding the proof.

Somehow, Lying George had discovered Klondike gold. The stampede was on.

____________________________________________________

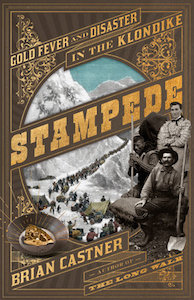

From STAMPEDE: Gold Fever and Disaster in the Klondike by Brian Castner. Reprinted by permission of Doubleday, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright (c) 2021 by Brian Castner.

Brian Castner

Brian Castner is a former Explosive Ordnance Disposal officer who received a Bronze Star for his service in the Iraq War. He is the author of two books, The Long Walk (2012) and All the Ways We Kill and Die (2016), and the co-editor of the anthology The Road Ahead (2017). His journalism and essays have appeared in Esquire, Wired, Vice, the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Atlantic, and other publications. He and his family live in Buffalo, New York.