His Lips Barely Move

You’re with him on the bus. Well, with him? Sitting just across from you, he’s here, elsewhere, everywhere. He is seven years old. The first year of elementary school. And this year, he really knows how to read. A few minutes ago, hardly out of the bookstore, he seized Yvan Pommaux’s little bo-ok with the lavender blue cover and immediately set off, vaguely aware of the reality around him—avoiding pedestrians a bit like a slalom skier makes his way between gates. Often people passing him smiled. And you feel rather proud to have an avid reader for a grandson.

Now, in the jolting traffic, you watch him in his bubble, so far away, so close. What’s fascinating is the imperceptible movement of his lips. He doesn’t wrinkle his forehead or knit his brow. But he’s not yet gliding effortlessly through the course. He has to do this deciphering, not yet completely fluid, exalted by his drive, his passion, his moving desire to possess the world he wants to escape into.

You’re sure that if you were reading that story to him, he’d smile often. But he isn’t smiling. He looks intent, serious. He’s creating his own lands of adventure, the quiet secret of his distance. His lips move. With small sips he’s drinking in the difficult magic of the breakaway.

It’s still work, and it’s already freedom. There’s a code. You don’t disturb him with questions like, “Do you like it? Is it good?” You know that sleepwalkers must not be taken by surprise. Nor do you want to bring him back to reality, the presence of a grandfather with his grandson on a crowded bus in the late afternoon. You get to fly by watching him fly. He has never looked so beautiful to you. His lips barely move.

Awesome!

At the end of gladiatorial combat, Roman emperors raised a thumb to spare the life of the defeated gladiator or lowered it to condemn him. Much later, in schoolyards, the raised thumb during a game of tag signaled a truce. These days, a thumbs up has become hyperbolic, expressing admiration beyond words. Nevertheless there can be a paradoxical nuance to this superlative form of enthusiasm. It involves a moment in soccer games that recurs frequently.

A striker breaks free, in hopes of getting a pass or a center delivered by a teammate. But the ball is intercepted by a defender, or flies well past the striker, out of reach. The usual impetuousness of soccer players would logically inspire a gesture of annoyance, or at least a show of disappointment after that useless run. But strangely, the frustrated player then turns toward the bungling teammate and offers an incongruous thumbs up.

This isn’t a matter of ironic congratulations, which the passer might just deserve. No, it’s much friendlier, apparently—and actually a bit more calculating, perhaps. With this falsely triumphant raised thumb, our striker celebrates the excellence of intention alone. Yes, it’s great that you tried to direct that pass to me. And above all, despite this first failure, keep your eye on me, keep calling on me, I depend on your good will, don’t be discouraged. Here we approach the finest subtleties of the game, which is, of course, collective, yet in which all players have their individual roles, protect their own interests, and play their personal career cards.

If I want to score goals, you must send me passes. With a thumbs up, I’m using the language of admiration to express entreaty. This also means, send passes to me rather than to someone else; we’re signing a kind of acknowledgment of debt here, too.

The stakes of professional soccer can prompt unnatural, inauthentic reactions, as well as crazes such as this, with children and amateurs on soccer fields everywhere restaging the drama, raising a thumb to salute the intention of a pass, however approximate. Awesome: you blew it!

Second Star

Almost ten o’clock. The late July night takes its time settling in, imparts a bit of mauve to the sky and the brown sand. They’re the last ones on the beach. Squeezed together in a square like a small, entrenched camp, they’ve endlessly delayed the moment for the picnic. They don’t own a vacation home and they aren’t renting one, not even an apartment, that’s immediately obvious. Later, they’ll have to pack into a car and return inland. No, two cars, there must be at least a dozen of them. The children played for a long time, letting out shrieks of horror when, with a few waves, the tide destroyed the last of the buttresses they’d built up by the shovelful. Let them make the most of it, there’s no hurry, they’re good here.

In the distance, the terrace lights come on at the Grand Hotel.

Can’t be too bad there, the ceremonial platters of seafood, the bottle of Sancerre beaded with icy sweat. But fine, let them battle with their crab legs. The cold chicken from the cooler is delicious, even better than at noon—a little wind was blowing sand then, the sun was beating down.

They ran, they swam, they got out rackets, balls, magazines. The men took naps, their faces in the shade of the beach umbrella. The old woman especially kept an eye on the others, a half-smile of camaraderie on her lips, offering a cheek for wet, hurried, distracted kisses. Now it’s getting cooler. They huddle together, back to back. There are still apricots to eat. There are long silences. Yes, it was a lovely Sunday. Waiting for the last of the traffic to clear up at the Nantes bridge. Waiting, putting off tomorrow. Waiting for the dissipating joys to make way for the idea of happiness, which makes you shiver. It’s just the night falling, pull on a sweater. Being so very much together, when others seem so very far away, and when you’re all in a square protecting each other.

—Are you asleep, Leila?

—No, I’m waiting for the second star.

Holding a Glass of Wine

You have a glass of wine in your hand, three fingers holding the bowl, thumb toward you, index and middle fin-

ger facing out, ring and little finger not needed for this scene. Because it is a performance, straight off, a posture—even and especially if you pretend to be looking elsewhere, to be deep in conversation. It’s all delectable.

Such a tall glass could seem precarious, but its roundness sits squarely in a firm hand that hides and seems to protect the red or white wine—it’s almost always red. This is an evening gesture, best when there are two of you, when words can be well spaced, leaving room for wide swaths of silence. Maybe you’ll have dinner, or not really. Maybe you’ve already eaten, not very much, and that was a long time ago, you only drank water.

It’s better when it’s dark outside. You wander from room to room, lamps low, scattered books. You put on soft music: Pavane pour une infante défunte, the perfect score for an evening that’s meant to last, that lasts.

Sometimes, when you’re on the elevated railway, you pass very close to apartments, and you see a woman exit a room, glass in hand, as though to celebrate her time and place. You envy her calm, detached profile, her absence, framed by the open curtains. She has that way of leaving without going anywhere. Holding a glass of wine, contained within you are these old images you’ve glimpsed, that self-possession you’ve imagined, all those distant pleasures silhouetted against the traffic. You aren’t having a drink. You hold a glass in your hand. You haven’t tasted the wine, or just barely, you don’t remember anymore, it doesn’t really matter. What matters is the holding, the holding back, the deferring, the not starting in, that’s the whole game. Where does this power come from? Every waking moment, in the very depths of each sleepless night, you’ve felt swallowed by time. And here you are in command, simply because the wine is there for the taking, and you haven’t downed it, you won’t let yourself taste or even smell it. It’s good to invent this distance from the goblet to the lips. But pleasure isn’t the point; the wine won’t improve with all the waiting. What’s really good is being yourself, your hand so nicely rounded, how you become this vaguely flattering, elegant gesture that only seems unconscious, this eternal thirst that’s never quenched.

__________________________________

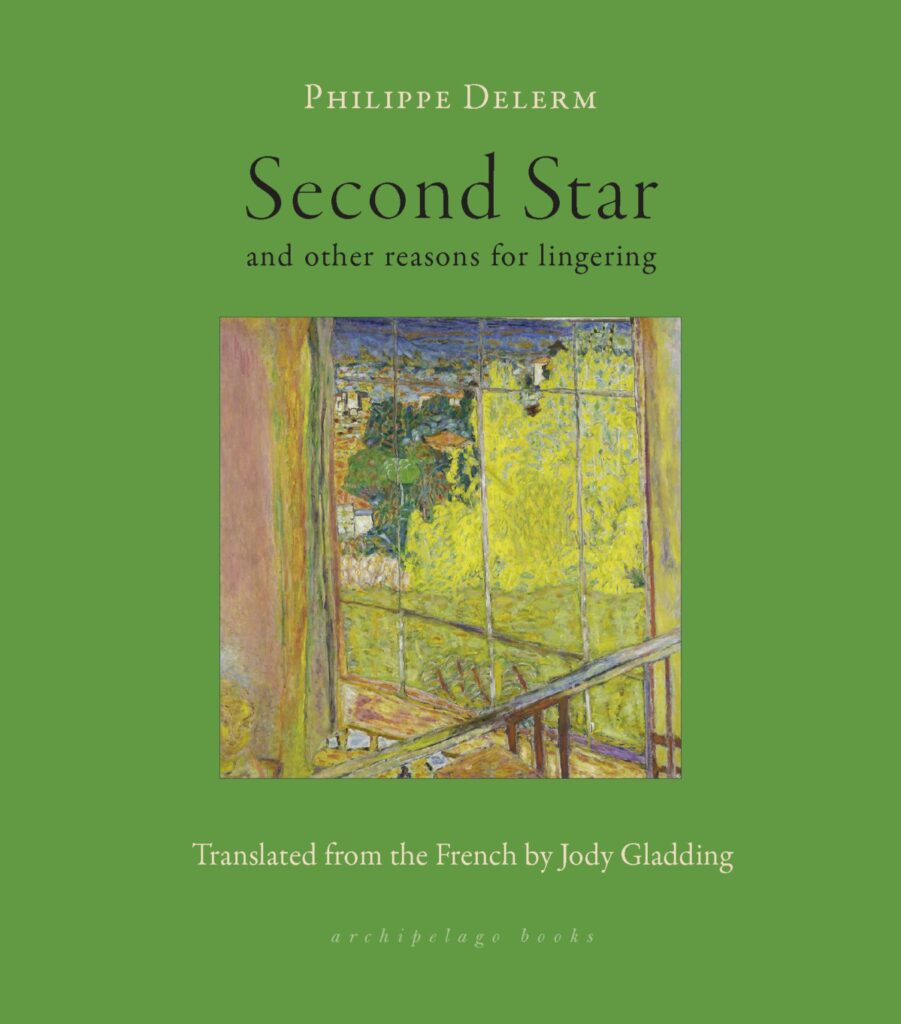

From Second Star: And Other Reasons for Lingering by Philippe Delerm. Used with permission of the publisher, Archipelago Books. Copyright © 2023 by Philippe Delerm. Translation copyright © 2023 by Jody Gladding.