A farm, dairy mostly, Ottawa Valley and family owned, therefore hodgepodge enough to include acres of grain, alfalfa, plots of produce we never bothered with. It was a summer job, not my first job, but certainly the first time I’d encountered labour that could be properly described as physical, gruelling, the kind that makes young men cry or quit. We were day labour, Derek and I—assigned to shadow Richie all day every day, tasked with doing whatever he asked and doing it quickly.

Richie was some version of regular farmhand, early twenties, remarkably strong though not physically massive; not family, but so intimate with the varying seasonal demands of the place he could’ve run it himself. There’d been no threatening aura about our terms of employment—no rural contempt for townie boys who’d lifted more beer cans than feed bags, résumés plumped out with dishwashing and food prep. The ask was simple: Give it a whirl. We need a hand. But if you find it too much, you’re gone.

In the array of menial tasks that need doing on farms, and setting aside the picking of stones, haying season is low on the metric of requisite technical skill. It’s hard work, done fast. A baler machine made the cutting easy, but getting those tonnes of hay off the land and into a loft according to a stopwatch meant bodies and sweat. The wagons with racks front and back had to be stacked twenty feet high, the bales in a geometrically interlocking system, then towed across fields, load by load, to the barn. Driver; a body stacking; a body at ground level hoicking bales up to the body stacking.

Outside of sport, this was my first experience confronting an obstinate, awkward, massive world with a body’s uncertain capacities and coordinations, its relative and unknown muscle strength. Not just a body’s uncertainty. A mind uncertain of what the body can do, can keep doing. The first time a bale twisted, lost shape, then dissolved into a mess brought on a hot sort of shame and frustration. The learning curve involved in wrestling baled hay is steep. The rows and fields repeat themselves like looped film.

You’ve to get the hang of the leverage gained by grabbing hold of a bale’s two lengths of twine, then pressing both forearms into the condensed hay low down at one end of the heavy cuboid. Now boost the cantilevered weight upward with the lower thigh until its mass bears down on parallel forearms—a forklift inverted—and then it’s like tossing a cabinet up the stairs. Repeat a few hundred times, and point the tractor at the haymow, where an elevator’s waiting, craning its neck up into the loft’s darkness like the reflection of a heron fishing.

Two in the loft and one hurling bales onto the ribbed, slick metal of the lift. They look docile, sleepy, like plump cakes lined up for display, and their butt ends flip up as they disappear off the upper lip one by one. Derek and Richie scramble in and out of shadow up there, working in tandem, piling base rows along the loft’s back wall, snug and jammed in. Both shirtless now in the oven and soon covered in a hellish chaff-and-dust mixture they eject from their nostrils out into the light. Whirling, glutinous, molecular structures of field snot, the prints from their work gloves making cat’s whiskers each side of their noses.

I was to be keeping up with them. I was having a hard time keeping up with them. The skies changed, and the winds were suddenly warm with chills buried inside. The first fat drops dinged off the elevator. In moments rain began to lash down. What we were already doing at pace now had to be sped up. I fell off the tiered wagon twice. I climbed down again when the motor went silent and the conveyor went still. Derek was pointing to the extension wire, unplugged from the AC power cord, lying snake-still in the pooling mess of grass and soaked straw with its fangs out.

Plug it in, dummy! Let’s go!

But— Plug! It! In!

I’m not sure—

—the violence of Saturday morning cartoons, reattaching a current while standing hip-deep in a flooded room. I was knocked off my feet, and strange, bone-deep sensations palsied my limbs. My lips buzzed like the thawing out from anaesthetics after dentistry. Derek was doubled over in fits of laughter, head and shoulders leaning out into the downpour. The bales were moving again. Once I’d regained my feet, I let my arms drift away from my hips slightly, turning my palms toward him.

I could’ve fucking died!

Yeah—he could barely get the words out, his face still folded six ways with the laughing—I know!

Derek was the sort of friend—irreverent, fearless, reckless, uncomplaining, jet fuelled, anarchic, loyal—from whom you learned things about the universe. Valuable lessons: abstract, koanish, proto-laws with deep internal contradictions. There’d be at least three more instances, before we began to lose touch, when we’d have fair cause to reach for the we-could-have-died gloss on events. A motorcycle accident. An upset man with a concealed weapon. Propane tanks and an engine fire. Why was it all so funny?

Why is it all so funny? This was two years almost to the day before Samuel Beckett died in a care home in Paris. I read of his death belatedly, flying alone one-way from Montreal to Dublin.

In Beckett’s Watt, Watt expends some arduous mental fuel trying to work out how to gain entry to Erskine’s room—Erskine being, like Watt, in the employ of Mr. Knott, residing there, like Watt, at Mr. Knott’s, for the duration. Watt is of the opinion that Erskine’s room contains a bell; this bell must be how Mr. Knott is hailed or answered or otherwise communicated with by Erskine when he, Erskine, is not within earshot of Mr. Knott, thinks Watt.

Anyway, he gets in. To Erskine’s room. Which does in fact contain a bell, but the bell therein is broken and of no use. Watt is none the wiser regarding communication, etc., etc., though there, on Erskine’s wall, hangs a picture. Watt’s attention is drawn to the picture, and the picture sets Watt to cogitating, painfully. We’re drawn a picture of the picture: “A circle, obviously described by a compass, and broken at its lowest point, occupied the middle foreground, of this picture. Was it receding? Watt had that impression. In the eastern background appeared a point, or dot. The circumference was black. The point was blue, but blue! The rest was white.”

Before choosing Paris as home, the man who’d go on to push literature out into the colder reaches of nonrepresentation—a kind of Kazimir Malevich of fiction—had been a diehard student of pictures. He’d concocted his own grand tour of the important galleries of Germany and Italy, spending hours upon hours in front of paintings he knew and more he didn’t. Taking notes, vast piles of notes.

Then reams of correspondence, which incorporated the notes into opinions and preferences and queries. Learning to articulate ideas about composition and mood, experiment and the modern, then returning the next day to sit again and look again. In 1936, in a fit of listless indirection, Beckett even wrote to Sergei Eisenstein, pleading to study under him at the Moscow State School of Cinematography. Eisenstein didn’t reply.

Echoes, tangents, correlations—when and where they occur—are my own willed patterning.Strangely, then, pictures never came to dominate Beckett’s literary work or even claim any conspicuous thematic undertones. It’s as though he began a process of not-seeing, or seeing the not-there. Though his output developed (de-developed?) more and more intensely toward pictures of mental landscapes, the mental landscapes themselves grew so deprived of setting, object, and contour that certain works have the feeling of occurring inside the reader’s head.

Passages, images, in the later great works, especially the short prose, worm their way into the bloodstream: litanies of partial phrasings, rephrasings, antiphrasings, following a music like evolutionary law, purposeless, eliminative. The silent, repetitive theatre of his and Suzanne’s forced seclusion in the Vaucluse during the war years planted a prosodic seed. A rhythm of labour and solipsism. Labour, solipsism, and an impinging threat of horror. There is little or no correspondence from late 1941 until the end of 1944, though Beckett was an obsessive (and entertaining) letter writer. What does survive from the vacuum that was 1942 to 1945 is the novel Watt, Beckett’s gateway drug into the full-blown experiments of the trilogy (Molloy, Malone Dies, The Unnamable), the great plays, and the shrinking, deracinated late miniatures. What does it mean to attempt an imagined “life” of Sam and Suzanne in those years alongside fragments of my own history: the folly of gluing a mirror to the backside of a mirror?

Echoes, tangents, correlations—when and where they occur—are my own willed patterning, a web I decided I needed and which is no more or less inane than any other necromancy. Perhaps my life’s been a palimpsest, layers of marginalia and endnotes from Watt and beyond. When low, I hear myself querying my illusory, faux-intimate relationship to the Beckett-in-my-head, the Beckett-in-residence, whose resonance and meaning are constituted at times by his work and at others by his lingering afterlife as interlocutor—as a beaky, corrugated assemblage of planes and pleats and ice pits, whose raptor stare is only prologue to a warmth and a wisdom about things not, in effect, getting better any day soon.

On a Monday in early June 1940, Beckett wrote to Marthe Arnaud, new partner of his painter friend Bram van Velde: “Under the blue glass Bram’s painting gives off a dark flame.” He’d just paid for a picture by van Velde in the attempt to help his friend financially, as well as arranging with Peggy Guggenheim that she should make a gallery visit with an eye to her own swelling collection. Paris was four days away from the first advance guards, followed by columns of the German Wehrmacht pouring down rue de Flandres.

Eventually, under blackout orders, ordinary Parisians who hadn’t left the city were directed to paint their windows using a solution of blue powder, water, and oil. People stunned or hostile or indifferent, depending, shuffled ghost-like through their private aquariums, then staggered through blackened streets for last drinks before bad turned to worse. Beckett finished the letter to Arnaud two days before he and Suzanne were to flee the city. “Today it will be something different.” He sounds as though he’s referring to the painting while referring to more than the painting. “You think you are choosing something, and it is always yourself that you choose; a self that you did not know, if you are lucky.”

*

Burying my father shared some of the emotionally muted, deflationary notes of what it must be like retrieving luggage lost by an airline, returned months later, once you’d determined your bags hadn’t contained anything of value anyway, and you’d been in effect lighter through the interim. Had someone in a position of authority (or even the bureaucratic middle uplands) made clear it was well within our prerogative—and would be entirely understandable—to have it disposed of, I think my brother and I might’ve plumped for that option and put down the phone.

As it was, my brother, the youngest of four, and likely for that reason in patchy contact with him the longest, ended up getting the call. Not from a luggage handler but our father’s sister, living not ten minutes away from the care home he was in, where he’d achieved nonresponsive status, winding down and gathering in, near Gander, Newfoundland. And here’s the thing, she didn’t want to have to deal with it. G—– came to mine, sat out back on the paving stones with a beer, and we passed a phone back and forth with our other two brothers on the line. I booked flights for the two of us and set about setting about setting my mind on Gander International Airport.

We bore down on the forested swathes bitten into by suburban builds and landed in drizzle, entered the small terminal, and were burped out again before the pale modular dividers had allowed even a glimpse at the gorgeous anomaly of mid-century design. We dropped our bags in town somewhere, so must’ve checked in. I remember the hospital corridor to his room; G—– had been getting texts from our aunt and from an attending nurse, and time, they were stressing, wasn’t in great supply. We stood outside the room and squared up to each other in a miasma of palliative disinfectant.

One of us asked, Who first? One went in, and the other went in after. Whichever went in first spent an undetermined amount of time inside with him, while the other stood in the corridor with the paint. While the one in the corridor saw paint and people bent or sitting, the other was in the room with him thrown upon them, hoping neither to hurt the one in the corridor nor waste the minutes in the room where waste lay. At an interval of time, the one in the room exited the room, and the one who’d been without purpose in the corridor was meant to go in where he lay supine and unresponsive.

So that one left the corridor and went into the room while the one who’d been in the room took up a posture and location much like the one from the corridor who’d just gone in. Some uncounted minutes expired. The last to be in the room came out of the room and again checked in or squared up with the one whose company had amounted to some cleaned paint and seated forms.

It’s as though he began a process of not-seeing, or seeing the not-there.Bit disappointing, no?

Bit disappointing.

…

…

I’d imagined hitting him on the flight.

On the flight.

Hitting him here. Imagined it on the flight.

I thought of the pillow thing from the movies. In there.

Stopping the beepy-beep?

Stopping the beepy-beep. Then maybe hitting him?

Drink?

Timezit?

It was an hour in the early evening in a Newfoundland town we knew nothing of other than the presence of locals who, though their numbers remained foggy, conjectural, bore our last name and…what that might mean we’d no clue. As brothers and as men of deliberation, we decided—while catching a bus into town, being of sound mind, cognizant of the beepy-beep and of mortal coils, of terminal exhalations and the being-no-more—to get properly and obliteratively oiled. Gander has bars for that. We went to some of them. We were expelled from one of them. I pitched into some gravel chasing a fox-faced boy I’d given money to for cocaine.

By this point, he wasn’t yet dead. Come morning, a drumming and chanting and what sounded like kicking at the door woke my brother, who responded with blue language. I believe I opened the door. A woman with a name badge and frosted hair stood in the corridor, flanked by two male employees of the hotel whose name badges must have been similarly pinned, though their breasts were obscured by their manager. I felt sure their purpose was to have us removed. I felt certain we’d broken or stolen or burned something. I felt sure they were inspecting the blood running in rivulets from my cheekbone where I’d removed the pillowcase that, over the course of the night, had baked itself into the dried, gravelly scab. It dripped onto my chest.

Mr. Babstock. She looked past me to my brother, still draped crossways over the single bed like a carp. Mr. Babstock. She wanted to include us both. We’ve been trying to wake you. I knew this much. Your family have been trying to reach you for hours. I veered mentally toward my son in Toronto. I’m sorry, but your father passed early this morning. You should really contact your family. My family’s here—I let an arm sway backward slightly, indicating the form on the bed—but thank you. Thank you. Sorry to’ve disturbed you. I hadn’t disturbed them. Had we? I was apologizing for my appearance, for answering their percussions and their bashing and hollering, and I went back to bed as nothing was now pressing and we wouldn’t be needed yet.

*

It was 1992, and I had nothing. Or, I had $7 and most of a pack of Player’s, but there was work if I wanted it in British Columbia. Getting west from Montreal, even by hitchhiking, requires food money. It’s a four-day drive, multiplied by however many days of being stranded outside Wawa, the Bermuda Triangle of transcontinental travel. And the work—planting trees in the northwest interior—I’d been informed, would require gear. So.

Seven hundred and fifty dollars in hand to spend seventy-two hours “volunteering” as test subject in a trial for a drug of some sort. It was a one-storey, blue glass–panelled complex somewhere in a light industrial zone north of the city. We’d been driven there in a company van, having eaten nothing in the previous twenty-four hours; a change of clothes, a book (if that was your thing), and our signatures on a consent form.

I’d been picked up off corners for manual day labour in the past and kept telling myself it was just like that, only with pharmaceuticals and no labour. Folding cots massed in gender-segregated “dormitories”—it appeared they’d simply shunted the desks to one side. A common area with televisions bolted to the pillars like a sports bar, ping pong, card tables, and soft chairs facing each other, quickly rearranged to not face each other. There was a low-security-prison, accoutrements-of-chronic-boredom feel to the place. We’d be eating and drinking a strictly controlled diet, they said. We’d be divided into a placebo group and a test group without knowing which was which, they said. And they’d be drawing blood every hour on the hour, they said, while a majority of our daylight hours would be spent taking a battery of cognitive tests.

The only test I remember involved a tangle of electrodes attached to my scalp, face, and fingers while I reclined in an armchair; a trolley of pre-poured alcoholic beverages (vodka orange) pulled up to my right. A pharmaceuticals operative pressed play on the television in front of me—Harrison Ford in Raiders of the Lost Ark—and said I could drink the vodka at whatever intervals I preferred but that I had to be finished the vodka before Harrison was done with the Nazis. I asked was there more vodka once these six were finished? They said no.

Once the movie had ended, I asked had I done well? I was asked didn’t I think spreading the beverages out over the course of the film would have made for a more pleasurable viewing experience? I said I hadn’t thought it would, no, and was shepherded off to have more blood taken.

*

Watt’s agon (or quest, or the plot of Watt), if it can be called that, in Watt, boils down to Watt’s urge to comprehend enough of Knott’s person, Knott’s premises, Knott’s purpose, while in his employ, at his house, that he might safely take his leave, as such time comes, while maintaining his, Watt’s, sanity. Success is not Watt’s in this.

Beckett’s invented setting is neither aiming for verisimilitude nor hinting at any definite point in historical time.We aren’t given much of Knott’s house by Beckett, but we do see the structure via the house’s basic appurtenances, named selectively and in passing, combined with the novel’s echoing, bare-walled tone: the credenza-and-spiders aura of an Edwardian household in decline, or stalled in perpetual decline, not ever having ascended anywhere. Watt, early on, “would have been glad to hear Erskine’s voice, wrapping up safe in words the kitchen space, the extraordinary newel-lamp, the stairs that were never the same and of which even the number of steps seemed to vary, from day to day, and from night to morning, and many other things in the house, and the bushes without and other garden growths,” though these all, presumably, lie arranged before Watt, should he himself be moved to describe them.

I’ve always imagined the grindingly senseless happenings of Watt to be occurring in a symmetrical, flat-fronted, two-storey house with dormers extruding from the tiled roof, its sash windows dripping from recent rain, the pebble-dash or white-plaster exterior developing stains like failing makeup beneath the grey-blue sills. Inside, I can count the broad planks of dark flooring, the few miniatures hung from single nails on the whitewashed walls.

The light, when there is light, pours in unobstructed, and heavy beams announce themselves on the upper floors. I’ve mashed up some surgeon’s late-Victorian, ivied house in Galway, now rentable on Airbnb, with ascetic Northern Renaissance interiors, and added a few Quaker elements, maybe a Bauhaus stair rail leading up to steel hospital beds in the upper quarters. In other words: everything very off the mark and anomalous. But Beckett’s invented setting is neither aiming for verisimilitude nor hinting at any definite point in historical time. Knott’s house is part workplace, part refuge, part institution—and partly the gearwheels of some enervating autonomous presence.

In fact, Beckett based Knott’s house, in part, at least, on Cooldrinagh, the home in well-off Foxrock where he was born and grew up. A mock-Tudor four-bed designed by an accomplished architect, it marked the family out; they now lived in the wellheeled suburban comfort Beckett’s businessman father had accrued over time. Standing on a full acre of landscaped greenery, gated and set back from the road, it’s where Beckett more than once found himself trapped, apparently without prospects and enclosed with his immediate family, before finally and forcefully decamping to Paris for good.

If this is so, the writing of Watt during Beckett’s war years of transience, fear, insecurity, and rootlessness means its central project—skewering the armour of the rationalist dream—could also be said to be haunted by questions of home. The finely appointed but oppressively miserable home of his origins followed him like a spectre from the basic Paris flat he fled with Suzanne through the innumerable “safe” houses, hotels, strangers’ beds, and wayside kips, and on to the years in Roussillon in the house he could only heat by trading his own labour. Maybe I’m seeing the psychic presence of his family home as the inverted negative of the catastrophic essentialist nostalgias that had Europe in a death spiral at the time. Ideas of home are not neutral. It’s possible that carrying around cracks in the first foundation— acknowledging the damp and subsidence—helps a person accept a cosmos flawed at its core.

__________________________________

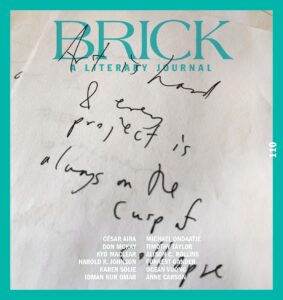

“Abandoned Lives” by Ken Babstock appears in the Winter 2023 issue of Brick.