Searching For Divine Love: On the Literary Landscape of Conversion Experiences

Terry Nguyen Explores the Intersection of Faith, Desire and Belonging

Last year, on an unseasonably warm November day, I went to mass. The idea came to me one afternoon, a random stranger knocking on the mind’s door. Not dangerous or unwelcome, but certainly unexpected. I let her in, picked up my keys, and walked to Our Lady of Sorrows Church. There, I stood, sat, and kneeled on cue. I did not pray or sing any praises, but during that hour I felt contained in the ritual of worship occurring before me. This containment evoked a calm that soon dissipated with the recessional hymn, and I rose from the pew to gather the loose threads of my psyche.

I spent most of November fraying at the seams. My marriage appeared to unravel overnight, although the cause of the blight had been festering in the relationship’s roots. The separation thoroughly ruptured my faith in human relations, revealing that two people who spend most days in close orbit can harbor vastly different interpretations of reality. I believed marriage to be the ultimate expression of faith in love: My husband and I eloped within a year of meeting. That now felt foolish and naïve. Our faith had recklessly impelled us toward a commitment that faith alone could not sustain. This has become the most difficult thing for me to fathom, because love still persists between us, or so I tell myself, just in a different form. Our marriage will be legally redacted in due time, but the sanctity of the gesture—the unfettered faith we felt, however briefly—could never be undone. I journaled excessively that month, but only questions seemed to arise: What happens after losing faith in love? What good is faith when I am untethered from reality?

Call it heartbreak, a crisis of faith, or what philosopher Ami Harbin calls disorientation: “sustained periods of life when we are coping with having been blindsided by major events.” I grasped for a new way of being by rummaging through the old closet of beliefs, where I’d left institutionalized religion and the vague adumbrations of high-school crushes. (I still think fondly of my first love, an altar boy three years my senior.)

This is the driving force of religion…an outward search for something or someone who answers the vast incomprehensibility of the human experience.

Most days, belief in anything beyond the day before me felt unfathomable. But my disorientation presented me with an opening, a paradoxical invitation to entertain what I would typically have considered beyond the barometer of belief. Only later did I realize that my crisis could itself be considered a kind of conversion: Old beliefs were suddenly thrown into question. My identity, too, felt indeterminate in this desultory period between separation and divorce. Our marriage was like the stale bread left over in the freezer that no one wants to throw out. I was still a wife but no longer a partner. A person of significance, but not of much daily relevance. I was somewhere in between—a half-convert, if you will. In this nascent state of disorder, I sought out conversion stories, like a child who turns to fairy tales for comfort. Feeling both soothed and discomfited, I read of people, even hardened atheists, being lightning-struck by revelation. How miraculous, I thought, to emerge from an experience freshly endowed with faith. To encounter an illuminated path in a dark forest. To hear a holy whisper in the dead of night. My zeal for these stories concealed a repressed envy toward the convert, her fulfilled fantasy of belonging. Saint Angela of Foligno, who converted when she was thirty-seven, attested to a hypostatic union with Christ; she felt that he was within her. Similarly, I longed to be confronted with what could heal me into a whole. Perhaps conversion could be the end to my inner forlornness, a salve for the godless state that Sartre supposes is part of life itself.

*

In the spirit of Kathleen Norris, who begins her own conversion essay by citing Mary Gaitskill, I turn to the poet Melody S. Gee, who details her faith journey in We Carry Smoke and Paper: Essays on the Grief and Hope of Conversion (2024). “I had been hungry for liturgy all my life,” Gee writes in the book’s third essay. “I had wanted to know where I belonged and to whom, to be shaped by rituals and not left to my own formation.”

Adopted as a baby from Taiwan, Gee was raised by two Chinese immigrants in Southern California. Her sense of filial estrangement, stemming from this early severing, is exacerbated by her adoptive family’s displaced origins. As immigrants, the Gees’ history is defined by disruptions of narrative continuity. Traditions are waylaid, revised, or simply forgotten in assimilation’s slow creep. Language, too, becomes a misplaced relic. Gee grieves the early loss of her biological mother tongue, Mandarin, which was supplanted by the Cantonese of her adoptive parents. And despite her fluency in Cantonese and English, language remains an imperfect tool for connection. Family conversations remain frustratingly stunted, even distant: “Each of our languages of intimacy was the other’s language of limitation.” At her grandfather’s funeral, it dawns on Gee that she knows close to nothing of his life. Naturally, Gee yearned for more—a kinship born not from obligation but inquisitive understanding.

The seeds of Gee’s religious turn grew from the rootlessness of her early life, a pattern reflected in the essays’ temporal itinerancy. Her narration leaps forward and backward in time, searching for scenes to imbue with post-hoc significance: the last Thanksgiving dinner her grandfather was healthy enough to eat downstairs; a visit to Guangdong, her mother’s hometown; the clumsy “pastiche” of traditions that made up her grandmother’s funeral. Because Gee’s parents “didn’t believe in God, but…ghosts,” she was raised according to their superstitious whims. The family constructed their own celebrations and customs to fill the gaps left by acculturation, but these were fragmented, almost irrational gestures, a patchwork of remnants. When Gee hosted a red egg party for her newborn, Gee’s mother printed out English-language instructions on how to conduct the Chinese ceremony. Lacking a cohesive tradition, Gee turned to Catholicism for its structured system of belief. She was drawn not only to the scripted, solemn liturgy but to faith’s broader linguistic blueprint—a “new language of mystery, sacredness, intimacy, gratitude, hope, and belonging.”

Conversion was the gradual learning of this new language, a process leading to “a more expansive self.” Cultivating faith demanded a confrontation with the desires Gee spent most of her life avoiding, an instinct learned from “a home where desires felt dangerous and imposing, the antithesis of sacrifice.” For the reader, this habit of avoidance has the frustrating effect of keeping Gee’s past at an arm’s length. She tends to parse through events with a cursory eye, relaying memories and feelings from an observational distance. Filial conflicts are not given much color (“When I woke up crestfallen instead of grateful, [my mother] took offense and left to work early”), as analyses of her family’s actions and motivations are chiefly driven by assumption: “No one ever spoke of China. No one spoke of immigration. No one spoke from ties or chains, of longing, grief, fracture, bitterness.” In this mode Gee loses steam, her sentences rendered abstract as she attempts to formulate a narrative from histories that have been withheld from her.

Gee’s prose is most expansive when she writes from her own inner experience, charting her spiritual evolution across thorny terrain. From her struggles with learning Spanish and imaginative prayer to her strides toward greater self-understanding, when Gee speaks from a place of embodiment, not avoidance, declaring her unabashed desire for belonging and acceptance, I feel most moved. Gee had been attending mass with her husband and children for years before embarking on the Rite of Christian Initiation for Adults. The process, however, felt needlessly slow and stilted. Seemingly random bureaucratic obstacles impeded Gee’s formal conversion, leading her to feel unwanted by the church and, by extension, God. “Maybe you’re not looking for God so much as how to have a relationship with God,” remarks her spiritual advisor. To which Gee later thinks, “All I knew was that I didn’t want to feel alone in my desire. I wanted to be wanted in return.”

I was touched by these glimpses of naked honesty. Here, Gee’s yearning felt as if it were my own. That unnerved me, as I do not turn to God to feel less alone in my desire; I’ve historically turned to other men. Still, the circumstances that engendered Gee’s conversion are not so different from what led to my own deconversion as a cradle Catholic. It surfaced from the murky waters of childhood, of feeling incomplete or simply incompatible with the family I was born into. Gee struggled to bridge the chasm between herself and her family. Through faith she finds a bigger context for her life than being “the container shaped like her [mother’s] daughter.” Gee’s conversion represents a turning, but also a departure: a turning away from the familiar—her family of origin—toward a broader community of faith. This ache, this longing not to feel alone in her desire, prompted her to seek out “a conversion toward the single self…in the belief that wholeness is what I am called to, what I am built for.” This is the driving force of religion and, I might add, romance: an outward search for something or someone who answers the vast incomprehensibility of the human experience.

In Eroticism: Death and Sensuality, philosopher Georges Bataille identifies the erotic as arising from a latent dissatisfaction with our isolated sense of self: “We are discontinuous beings, individuals who perish in isolation in the midst of an incomprehensible adventure, but we yearn for our lost continuity….There stands our obsession with a primal continuity linking us with everything that is.” This primal continuity is ultimately found in death, Bataille claims, a driving force of religion. God can serve as a proxy for this erotic instinct, dissolving the sense of separateness between individuals. Like Gee, I’ve hungered for some form of continuity, some organizing principle to make sense of my inner restlessness. My Catholic upbringing encased me in the tedium of its rituals. I understood religion as routine and prayer as duty, never devotion. I had no desire to belong to my parish, even as I became an altar server, received the sacraments, and participated in youth ministry. The notion never crossed my mind, much as a child doesn’t think about whether they belong to their family. My departure from the church was protracted and anticlimactic, even as I was experiencing the rapturous intensity of a different kind of conversion: Like many teenagers, I became a devoted proselyte of romance.

“Desire,” writes philosopher Lauren Berlant, “visits you as an impact from the outside, and yet, inducing an encounter with your affects, makes you feel as though it comes from within you.” Substitute “God” for “desire” and Berlant’s point still holds. Within the conversion story lies an inchoate erotic urge. “It has been stated that our need to love lies in the experience of separateness and the resulting need to overcome the anxiety of separateness by the experience of union,” writes psychologist Erich Fromm, echoing Bataille. This overcoming is explicitly encoded in the liturgy: Receiving the Eucharist is a reunion with the body of Christ. Converts, in return, “offer [their] bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and pleasing to God.” But this experience need not be limited to Catholicism’s terms of repentance, for the church offers only one kind of erotic container. (Fromm writes that religious love is “psychologically speaking, not different” from romantic love.) Let us consider conversion, in general terms, as a turning in the direction of desire, an event that induces a departure from the old self, one’s old way of being. And in spite of the inner change faith induces, converts rarely speak of it as a conscious decision but as a potent fact that intervenes, imposes, and persuades. There is a mystic register to this faithful wanting, religious or otherwise. One feels chosen by the object of one’s desire, even as the locus of conversion remains unknowable, shrouded in some unconscious need. Recall what Plato wrote in The Symposium: It may be impossible to truly know what one desires, for “the soul of each is wishing for something else that it cannot express, only divining and darkly hinting what it wishes.”

*

Once the grief of the separation from my husband had settled like a dormant volcano, I began to investigate the unfamiliar topography of my desire. Historically, I’ve operated on instinct, responding to the animal that is feeling. Such pursuits have been, I now realize, attempts at self-eradication. Reading Gee, I wondered whether I’d have received some semblance of spiritual fulfillment had I instead turned to God. Surely I’d have saved myself some embarrassment. For a woman who devotes herself to God is a mystic, whereas a woman who lusts after a mortal man is a fool. This line of thinking, I’m aware, introduces a false binary. And matters of faith, of course, are never quite so cut-and-dried.

In Graham Greene’s The End of the Affair (1951), faith is the destabilizing force that drives Sarah Miles, the novel’s adulteress-turned-convert, to the brink of sanity. For Sarah, eros serves as a powerful conduit for the divine, but the divine is not without brutality nor chaos. When she confesses to catching “belief like a disease,” her plaintive longing is nearly painful to behold—for both the reader and her lover, Maurice Bendrix, who learns of Sarah’s newfound faith through a stolen journal. “I’ve fallen into belief like I fell in love,” Sarah writes. It was love, after all, that led Sarah to faith, her desire the thoroughfare by which she encountered God. When Sarah finds Maurice struck unconscious in an air raid, she kneels down to pray for the first time in her life. Believing him dead, Sarah promises to give up the affair if God lets her lover live. This prayer-promise becomes the basis for Sarah’s spiritual initiation. She resists, and resists with resolve, until it dawns on her that her anguished fury at God is proof of faith itself. Her conversion is not a single moment of startling clarity but a series of false starts and slights. Then comes faith’s inevitable freefall.

A more pious writer might’ve positioned faith as a path to redemption, reconciling Sarah and her husband. Instead, Greene has God—or rather, Sarah’s relationship with God—wreak great suffering upon her psyche. Faith only further alienates Sarah from those who love her. Divine love exhausts Sarah and makes her physically ill. Her fate recalls Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s assertion in The Cost of Discipleship, “When Christ calls a man, he bids him come and die.” Only in the “primal continuity” of death—the ultimate reunion with God—does Sarah find relief.

Perhaps there is a holiness to our indeterminacy, in this state of hope-in-nothingness, of longing to simultaneously be lost but also found in one’s lostness.

The End of the Affair does not present an optimistic picture of human love: Eros is a means to an end—a fatalistic step on the ladder toward agape. Given that Greene’s own heterodox religious turn was prompted by his mistress, it’s not difficult to imagine Bendrix’s petulant frustration as a proxy for Greene’s. Sarah’s conversion can thus be read as an indictment of what she calls “ordinary corrupt human love”—a false idol that toys with our emotions, distracting us from the greater love of God. But the lesson I took from Sarah’s death (whether or not Greene even intended there to be one) is that unfettered religious devotion comes at the expense of joy, even life.

Clarice Lispector’s An Apprenticeship or the Book of Pleasures is an expansive counterpoint to The End of the Affair, depicting conversion as a humble meandering through the fog of self. I related, of course, to Lispector’s Lóri, a depressed and reserved schoolteacher who “was a worshipper of men” and had “a childish wish” to be protected. She imagines protection as a kind of paradoxical freedom, of “no longer being one single body.”

Most of the novel is a dialogue between Lóri and “the God” inside her, as she prepares for a mystical transformation that will, in due time, allow her to consummate her relationship with Ulisses, a philosophy professor. Lóri and Ulisses meet by chance on a street corner. He approaches her believing they are fated to be lovers but declares that she is not yet ready for their friendship to blossom into romance. Lóri recognizes that “Ulisses’s human condition [is] greater than hers” and so follows his opaque lead, though the precise nature of their goal remains unclear. The reader’s path is equally murky, as Lispector navigates the sinuous contours of Lóri’s psyche. The experience of reading the novel can, at times, feel like a test of faith. The title, The Apprenticeship, refers to Lóri’s spiritual tutelage but also extends to the reader’s relationship to Lispector: The novelist’s hand never strays from the reader’s back.

Most love stories follow a common formula: The lovers face obstacles to their union. Rarely are the obstacles presented in such nebulous terms as in The Apprenticeship, which demands of its lovers something deeply internal: an apophatic self-actualization that results in less knowledge. Lispector dispenses with the romantic ideal of knowing your lover as well as yourself. This concept of “not understanding,” Lóri realizes, “was so vast that it surpassed all understanding—understanding was always limited. But not-understanding had no frontiers and led to the infinite, to the God.”

Not-understanding is not a state of not questioning, of obedient muteness. Rather, it supposes a limitless faith in the abyss that can be found in the turmoil of questioning. Lispector frames this as a “struggling with the God.” Lóri oscillates between hopelessness and a hope-in-nothingness when she finally admits she doesn’t understand anything: “It was such an indubitable truth that both her body and her soul sagged somewhat and so she rested a little. In that instant she was just one of the women of the world, and not an I, and joined as if for an eternal and aimless march of men and women on pilgrimage toward the Nothing. What was a Nothing was exactly the Everything.” Here, Lispector offers a counter to the godless existentialism of Sartre, which reduces one to a purposeless, directionless, and isolated state. The apophatic gestures in The Apprenticeship allude to a truth in skepticism, in the interminable questioning that is intrinsic to living—the convert’s ability to live the questions through her relationship to God.

Contemporary writers like Gee and Norris plumb their personal histories to determine when they were first touched by faith’s latent mundanity. Their accounts, as a result, follow a logic of inevitability, colored by their present-day convictions. “I have little idea how to account for the change,” Norris, who grew up Catholic, writes in Amazing Grace: A Vocabulary of Faith. “For years I had drifted through life, more or less aimlessly, with little in the way of religious moorings, little sense of connection or commitment to other people.” As it did for Norris, participating in mass slaked Gee’s thirst for community and a sense of togetherness. “It was the shared ritual that called me, that kept me coming back even before I fully understood why I had shown up,” Gee writes.

Norris and Gee don’t shy away from doubt, what the writer Patricia Lockwood calls “the dimension of the religious experience that brings it into reality,” but their doubting is rarely enacted in the process of writing. Doubt is contemplated from a distance, with knowing confidence. Perhaps this is a limitation of personal writing, which narrates from the retrospective perch of self-knowledge, whereas fiction and poetry grant the writer a wider berth to suspend herself (and her characters) in inquiry. Indeed, there is a difference between a text that delineates its writer’s spiritual transformation and a truly transformative text, the latter striving to abolish the distance between reader and writer, allowing the skeptic to live in the mind of the believer, at least for a moment, or vice versa. Shouldn’t the conversion story, in its form, facilitate this ardent self-abandonment? Selfishly, my hope as a reader is not to be persuaded, but to succumb to the pulsing psyche on the page.

The philosopher Rachel Aumiller writes that the “skeptic is one who embraces the failure of conversion to achieve unity.” Conversion, according to Aumiller, does not always lead to a complete rejection of one’s “former way of being-in-the-world.” The skeptic simply accepts these repeated failures and finds a paradoxical pleasure in the pursuit. There are moments when, in thinking about my marriage, I am struck by a bout of regret. I become flushed with embarrassment or overcome with an unshakeable sorrow. For months, I wished to free myself from this liminality so I could stop dwelling on my marriage’s utter failure. What I wanted was closure, a kind of verbalized assurance in service of the obvious. “Closure isn’t real,” my husband would say whenever I broached the topic. I remember him saying it sadly, as if he too were denying himself something. But perhaps there is a holiness to our indeterminacy, in this state of hope-in-nothingness, of longing to simultaneously be lost but also found in one’s lostness. I realized recently that the words verse and conversion share the same Latin root: vertere, to turn. What is a line of verse but an instrument of the self in process, from which one may derive an inchoate understanding of faith?

__________________________________

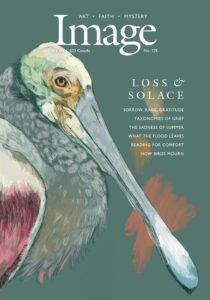

“Fraying at the Seams: Conversion Stories as Comfort Reads” by Terry Nguyen appears in the latest issue of Image Journal.

Terry Nguyen

Terry Nguyen is an essayist, critic, and poet from Garden Grove, California. She writes Vague Blue, a newsletter on Substack, and is an incoming MFA candidate in poetry at Columbia University.