The kids at Calvin Village Elementary School made me feel better and worse about myself. I often thought about how every adult in my childhood had done me wrong and how angry that made me, but at least I didn’t have it like the kids at Calvin Village. The last school nurse sent most of the kids home with notes saying they needed to be treated for ADHD. Just for doing things like interrupting their teachers or fidgeting in their seat—these dusty kids who couldn’t afford breakfast, had no qualified teachers in their schools, and had the constant presence of the county prison looming from the horizon at all times. She was actually fired after being caught handing a child pills without a prescription. Dropping them into a boy’s open mouth and closing it with her hand, watching him fizzle out and droop against the hallway walls. He told his parents about the candy the nurse had given him to help him stay focused in class.

After she left, the kids were still either slushy and melting against their desks or running like little comets through the halls. I was hired as the replacement, with no qualifications or experience. I had an uncompleted bachelor’s in nutrition, and the school said this was enough. They just needed someone to give out Band-Aids and ice packs like a normal school nurse would. Give them tissues to stop their nosebleeds. Little containers to carry their loose teeth home in. I just tried not to make them any worse.

Gertie was my favorite. When I first started working there, she came in all the time during lunch. Other children would come in sniffling, sobbing while cradling whatever scrape or bump they had, guided by a teacher or a group of friends. But Gertie would just solemnly walk to the entrance and proclaim the problem, like a third-grade politician: I scraped my knee. I have a bruise. My stomach hurts. Then she’d sit and eat some loose fruit snacks from her pocket.

She was so stone faced, like a small adult. Even her name was tragically geriatric: Gertrude. I once tried calling her Gert, after feeling strange about the silence passing between us. She had snapped her head up to look at me and scowled. I understood immediately: there was no fixing the name Gertie in any way. Our relationship was conditional on the maturity between us both. She didn’t want to be treated like a child.

I had gotten used to our meetings and looked forward to them. I started offering her a chair on the opposite side of my desk after I iced whatever scratch or bruise she had that day, and we ate while reading from the outdated medical journals my girlfriend Kelly subscribed to. She told me that I didn’t need to read any of them to be a school nurse, but I liked to think that I could have absorbed something useful. Sometimes I would see Gertie try to rip out pages very quietly and fold them into her pockets, so at least she was getting something out of them.

One day she kicked the metal desk, and the noise made me flinch. She watched me with her still face. “You wanna see something?”

“Sure,” I shrugged, trying to find some line between caring, enthusiastic adult and casual colleague. She reached her hand into the pocket of her school uniform, and I noticed for the first time that it was dark and wet. She set it down on my desk: a limp brown mouse, with drying blood on its fur.

I knew Gertie wasn’t shy around animals. Her father, Mr. Holt, had a farm, and a noisy sty of pigs that I saw when I drove to work each morning. An unspoken segregation cut through the town. My apartment with Kelly was on the nicer part of town—which just meant that the houses had a second floor and the patch of grass out front was actually green. On multiple occasions, some sugar-voiced pageant retiree had come up to me and blocked my way to my front door. Now honey, where do you live? And I would stand and find several different ways to say I lived on the second floor until Kelly came back home to let me in. The snorting signal of Gertie and her father’s sty was a bittersweet signal that I had returned to where I belonged. Mr. Holt trained the piglets to race in order to take the fastest to the Oklahoma City State Fair, and I’d sometimes see him standing on one end of his field yelling to the piglets while Gertie held an apple skewered on a sharp stick, running over little dirt hills to lure them back to her father.

I liked Gertie for this reason as well: She was bullied. I don’t think she was any poorer than most people in town, but she came to school dusty kneed and her plaits uneven. Her perpetually sullen face didn’t do anything to help her. She looked ready for a fight at all times. I liked the idea that I was a place of solace for her. And that someday when she thought of me, she’d credit me as the one grown-up who was looking out for her.

I had confided to Kelly about this indulgent daydream while resting my head in her lap.

“I’ll have been the one who gave her a place to grow, you know?”

“I love you so much,” she had said, “but don’t count on it.”

So, I smiled at Gertie, pointed at the little mouse, and asked her if she found it that way.

“Yes,” she said, still analyzing my face.

“Wow,” I said. “That’s cool. That’s so cool.”

She nodded like I had passed a test, and I felt a rush. She scooped the dead mouse back into her pocket and leaned back in her chair with a medical magazine. There was a red smear mark on the table.

On the outside nothing changed. She didn’t smile or become more talkative, and we were both still hiding away in the nurse’s office. But now I felt like I had a clear purpose in my job, one that meant more than passing out bandages. I didn’t tell anyone, not even Kelly, in part because I didn’t want the illusion ruined—and I didn’t want to lose Gertie’s trust.

Every day, she showed me a new small dead thing: scorpions from her pocket, crushed hummingbirds found in bushes. And each time I couldn’t wait to tell her how cool she was for showing these things to me.

*

Kelly died a few months into my routine with Gertie. She had been studying to be a nurse and was far more driven than I knew how to be. Being gay in that town was bad enough, but the friends who mustered up the courtesy to get to know Kelly’s girlfriend always seemed ready to stage an intervention after knowing the different paths we were on. Or at least it felt like that to me. Kelly: soon to be a well-paid nurse. Crystal: lingering dropout, now working as an underfunded school’s last resort. I couldn’t really keep up with her, so I didn’t try, just stood by with hot coffee during her all-nighters.

She died in a fire at her college, the only one in town: an expensive private university to get these already poor kids to fall into the trap of debt. The lack of oxygen killed her, not the burning. Her parents wiped away the soot from her body and kept her on ice. They told everyone all about the chemicals that funeral homes pump into your family when they die, just to take your money. They thought human beings were too disconnected from death—human beings could not process and grieve the death of a loved one if someone was paid tens of thousands of dollars to make them look like they were still alive. They were hippy spiritual types. Wind chime types. Crystals lined up on their porch. It was warmer outside in the snow than in their house, where they sat around in sweaters and scarves, sipping hot tea with little flower petals floating on top.

The ice was packed underneath and around her body.

Her skin was gray, and her folded hands still had black soot in the half-moons of her nails. I wanted to reach out and touch her forehead. It was the way her parents still talked about her. Go ahead, Crystal, Kelly’s waiting for you. Ooh, are these camellias? Kelly will love these. She loves these. It kickstarted a little flutter in my chest and made me think that she was still alive, just very sick and waiting for me to wake her. But I knew that if I touched her skin, I’d want to throw up. So I just placed the little bouquets I got from the corner store in the Hobby Lobby parking lot on the coffee table and told myself that Kelly would probably be up the next time I saw her.

*

I didn’t take any days off after Kelly died. I didn’t even cry. Kelly’s parents tried to encourage me to go home and rest—sent me off with a flask of tea that tasted like how sweaty feet smelled. But every time I tried to lie down, pressure gathered in the air and pressed down onto my chest. I sat up choking every few minutes, and when Monday came along I showed up to work just before the sun peeked over the horizon, when the sky pulsed violet. I passed Mr. Holt’s farm. He was out front alone, kneeling in the sty with his pigs. He rose up from his knees holding one of the piglets. It was still and limp like rope in his arms. He stared at it, his body equally still and shoulders drawn up tight. The other piglets squealed around his ankles, snorting and puffing up fog from their warm snouts.

That day, Gertie dropped a dead lizard on my desk—a big blue lizard with half its tail cut off. I didn’t know anything like that even lived in Oklahoma, but I was too slow to tell her I thought it was cool. Any words I could say were vomit building up in my throat. Gertie noticed.

“You don’t like it.”

“I like it,” I croaked. “You look sick.”

This threw me off, and suddenly my face was hot. I didn’t like the idea of seeming weak in front of her.

“I didn’t get a lot of sleep is all.” Then, out of fear of making Gertie feel as if I was keeping her in a child’s place, I said, “Someone I know is sick. She’s dying.”

Gertie sat back in her seat, a pensive tilt to her head. It eased the weight of my shoulders a bit to see that I had said something that interested her, and I was about to ask her about her classes when she asked, “What are you going to do about it?”

“There isn’t much to do about it.” “You’re not even going to try?”

A pit burrowed in my stomach. “That isn’t something you can do.”

Gertie frowned and hopped out of her seat. I stood up, thinking she might leave, but she just crouched down near her backpack and fished out a crinkled medical magazine.

She spread it to a dog-eared page and turned it so I could see. “These guys are doing it, I think. So am I.”

My eyes skimmed across the article, packed with a bunch of science jargon I couldn’t really make out. There was a lot about pigs.

Gertie’s words caught up with me. “What exactly have you been doing?”

After school, Gertie took me to a twisted grove that led to her house. It was sparse, especially with the ice taking the place of leaves, but the black branches curled in around us like gnarled hands.

A ripped-up garbage bag sat tented up on the ground, and Gertie lifted it up to reveal three short planks of wood perched against each other. She took the wood down to display her collection: a few bent-up straws, a cut-off rubber hose, some exposed electrical wires, a pair of scissors, and the most recent dead animals that Gertie had shown me.

The animals were black and stiff, dismembered, with their stomachs and heads stuffed with straws and tubes.

I stumbled back and gagged, using my shirt to cover the smell of rot and also to wipe the sweat beading up on my burning skin. “Gertie, what the hell? Why are you keeping this here?”

She rushed to defend herself. “Because I can’t keep it at home. My daddy wouldn’t like it.”

I tried to calm down, to get my stomach to stop flipping in on itself. I squatted down with my shirt still pulled over my face and picked out the loose wires with my finger. “Why this?”

“I was trying to put electricity in it.” She pointed to a branch on a tree where some ruddy loose pieces of dental floss flittered in the air. “The article said it works better if they’re upside down.”

A fly twitched across the caved-in eye of a squirrel. “Gertie, I’m not sure if any of this would work out.

Those guys who did this had teams and like—a lab. Equipment.”

“You could be my team.”

My shirt fell from my face. I stared at her. “What?” “You can help me—and maybe you can buy some of the

things we need because you’re an adult. And then maybe if we make one of the animals come back to life, we can keep your friend from dying.”

“What makes you think I could do this?” Gertie tilted her head to the side. “You can’t?”

Something kicked up in my chest. I wanted to tell her no, I couldn’t do whatever it was that she was asking me to do. But those words felt like some kind of magic spell, and saying them would break whatever powers led Gertie to believe that I was someone who could reverse death. The longer I let the question sit, the more confused I was by my own hesitation. Why couldn’t I bring an animal back to life? Gertie thought I could do it. Of course I could help. I told her so. She simply nodded and began to cover her animals back up, and suddenly bringing a dead thing back to life felt like something I had been doing my whole life—as sure as breathing.

*

I spent the night reading through that article. Looking back, it was extremely complex and involved a lot of expensive machinery I couldn’t afford and would never be able to afford. The point was to get blood flowing back into a dead body again. Veins and capillaries shriveled up after death, like a dry river. The scientists in the article weren’t even able to bring an animal back to life—not in any sort of Mary Shelley way. But they did get enough life back into the brain of a pig for it to be slightly alive. Slightly alive was better than completely dead.

We set up in my apartment. I didn’t want anyone to see me kneeling in the woods with a child, playing with animal corpses. If you’re thinking about how a child in my home looked much, much worse, you have to understand that our town was slow to catch up on the value of children’s safety. I wrote a note saying I was Gertie’s in-school tutor who was helping her with math. I gave it to Gertie to give to Mr. Holt, and she was at my place the next day.

“What did he say?”

Gertie shrugged and dropped her things down like she lived there. “He didn’t really look at it. He’s busy with the pigs.”

After visiting Kelly, I would start the day by meeting Gertie on the other side of the woods. We’d wade through the red mud and find little animals. Sometimes Gertie would pop a bird with a stone, and sometimes I’d stick my hand down mice burrows or dive to snatch a lizard from underneath a rock. This impressed Gertie, so I made a point to do it every time we met up—I spent all our time together slathered in mud.

I hadn’t slept since Kelly died, and I didn’t sleep for an entire week while I helped Gertie. I survived on coffee, determination, and praise from Gertie. I hung rodents by their feet from wire hangers, sticking needles and tubes into their limp bodies, and she’d look up at me, dark eyes shining like a peering bird. I wanted to skin animals forever just to keep her looking up at me. I sliced the bellies of rats, and she held a bucket underneath to catch the blood. We cracked open woodpecker skulls, and I held sliced brains steady in my palm while guiding Gertie on getting the needle into a vein.

When she became cross-eyed and her hands were too shaky, I made her hot chocolate and she sat down in the hall to watch me work. We had to keep the apartment cold, so I wrapped her up in my scarf. She would fall asleep while I rinsed my hands off in the sink, watching the water run clear.

*

My heart fell into this practice smoothly—visit Kelly, go to school, dismember animals at my apartment, and drive Gertie back home.

I had almost forgotten why we were doing all this.

A little more than a week after her death, Kelly’s parents told me they were going to take her home.

I blinked at them. “But—she is home.”

“Oh, no sweetie,” said her mother, “we mean her permanent home.” She glanced up at the sky a little.

My mouth felt like drywall.

“How soon? You can’t keep her a little longer?”

Her parents looked at each other. Sharing the same thought. “Well, Crystal, everyone’s had a chance to say goodbye—and it’s a lot of upkeep.”

“Kelly?” I scoffed.

“Her body, sweetie.”

I looked at Kelly, and it was as if the strange, bright tint that Gertie had put on my perception suddenly switched off. The black soot in her nails seemed starker, set in. As if it was a part of her now. Her face had started sinking.

I stormed out, sweaty and fuming. A week’s worth of exhaustion piled onto my back, and the crushing feeling in my chest pressed down hard, leaving me gasping in the seat of my car, clenching the steering wheel with my clammy hands. I hated myself for looking like a child in front of Kelly’s parents, I hated myself for not being fast enough for Kelly, and I hated myself for possibly failing Gertie. Failing her felt like death, and my thoughts hummed with all the ways I planned to keep myself alive.

*

Gertie was off that same day. Instead of sitting in the nurse’s office with her calm blank demeanor, she spent the whole lunch period looking like someone had pulled down hooks at the corners of her mouth. In my apartment she was more tense, her little shoulders hunched up and her face turning red in the center.

The animals that we kept in Tupperware and dog cages skittered against their containers. Her hands shook as she tried to guide a syringe in a bird’s plucked neck. She kept poking it in the face, scratching it against the beak.

I tried to speak calmly to her, tried to guide her, but she threw the syringe down on the ground.

“It’s fine,” I said. “I can do it.”

“They’re too small,” she huffed.

The veins of the bird. We were supposed to get blood flowing through capillaries, which we couldn’t even see, and the veins of the little animals we had caught were still hair thin. I had tried something bigger this time: a crow I had hit with my car that morning.

“That’s okay, we can just try something bigger—”

The words next time died on my lips. Kelly was being buried tomorrow. There was not going to be a next time, but the weight of that hadn’t caught up with me yet. Not with Gertie around.

She began to cry, quiet and sniffling like she was trying to make the tears go backward.

Watching her cry was like watching a new car begin to break down, like watching an animal rot rapidly in front of your face. I kneeled down and tried to get her to stop. I stroked her hair and told her things were fine—Don’t cry, please stop crying.

Her words whined from her mouth like a deflating

balloon. “Hoover is dying.” “Hoover?”

“My pig,” she sniffed, gasping between her words. “All the pigs are getting sick and dying, and Hoover is next.”

I stared at her. “Oh, you and your daddy do those pig races. Are you upset because you can’t join the state fair now?”

She stared at me blankly before shaking her head. “Hoover isn’t a racing piglet. He’s just mine.”

I was so confused by her crying. I didn’t see her as a child who could get upset about pigs dying. I didn’t really see her as a child at all, so her crying felt more like a coworker suddenly breaking down during their shift about their pet possibly dying. It felt understandable but strange and inappropriate.

“I don’t want to do this anymore,” said Gertie.

“What? You can’t stop. You’re so close. We just need something bigger. I can get that for you.”

“I want to be done, Miss Crystal.”

“Gertie, you’re giving up so easily.” I kneeled down to face her, feeling frantic. “Great people in the world don’t just give up after a week. Scientists and doctors and actors and anyone good at anything have to work for a long time. It takes months and years to get to something this great—and sometimes you don’t even get to what you’re reaching for. But I know you can.”

She shrunk back, vanishing in front of my eyes. A small wet thing I could hold in my palm. “Miss Crystal.”

I took her cold hands in mine. “I can help you be great.”

She looked down to the ground. “I don’t want to.” She tried to slip away.

“Gertie, come on,” I pleaded.

She snatched her hands away from mine and fell back to the floor. I went to help her up, but she kicked me in the stomach. She kept kicking and screaming, knocking her fists against the ground.

All the animals in their cages flapped and thumped at the noise, shrieking and squeaking along with Gertie. The noise rose and wrapped itself around me, pulling tighter and tighter, and my chest closed in on itself.

__________________________________

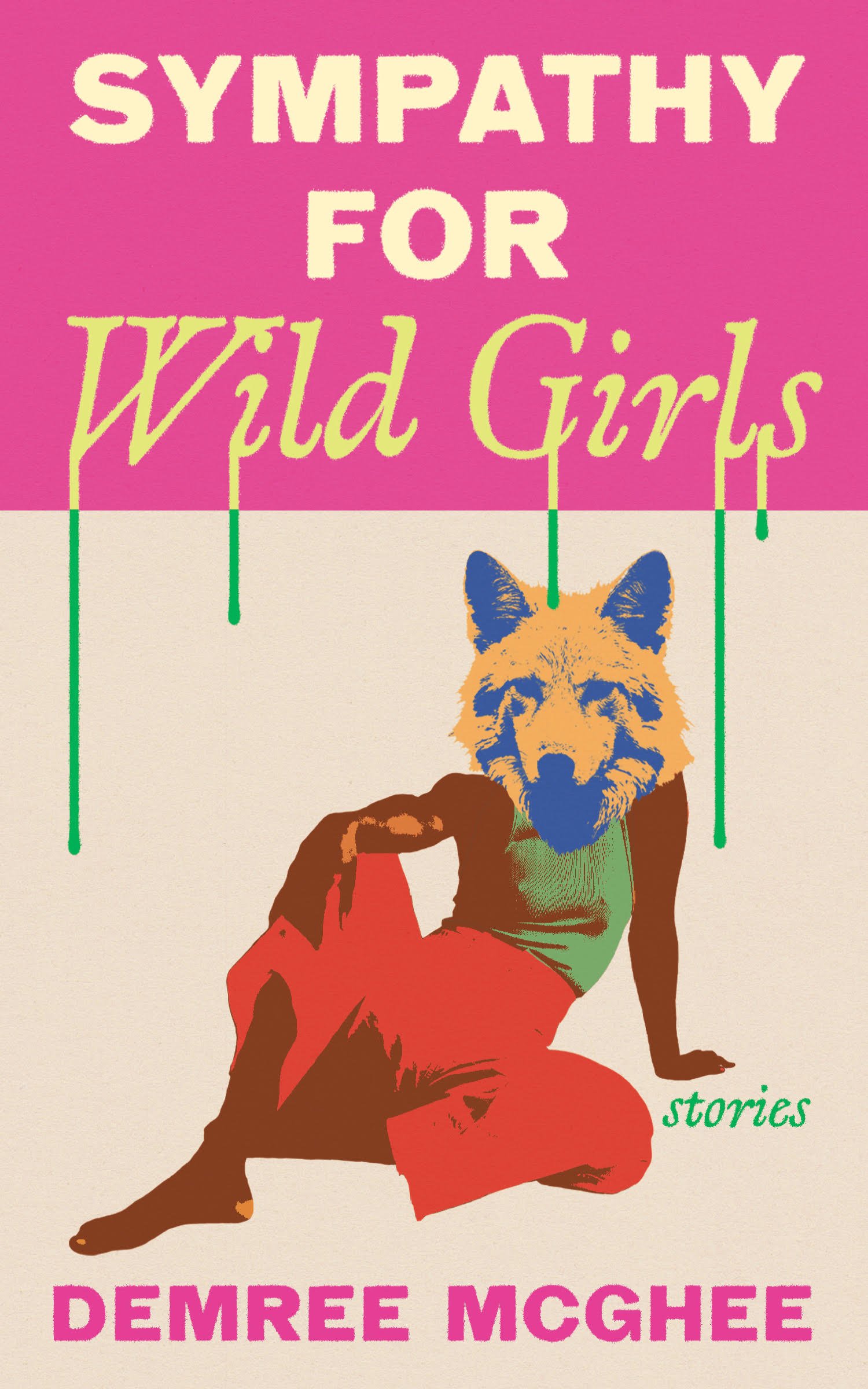

From Sympathy for Wild Girls by Demree McGhee. Used with permission of the publisher, Feminist Press. Copyright © 2025 by Demree McGhee.