Scott Guild on Trying to Read Finnegans Wake While on Tour With His Band

“You won’t just write song lyrics about your anxieties all day. You can reconnect to literature on the road!”

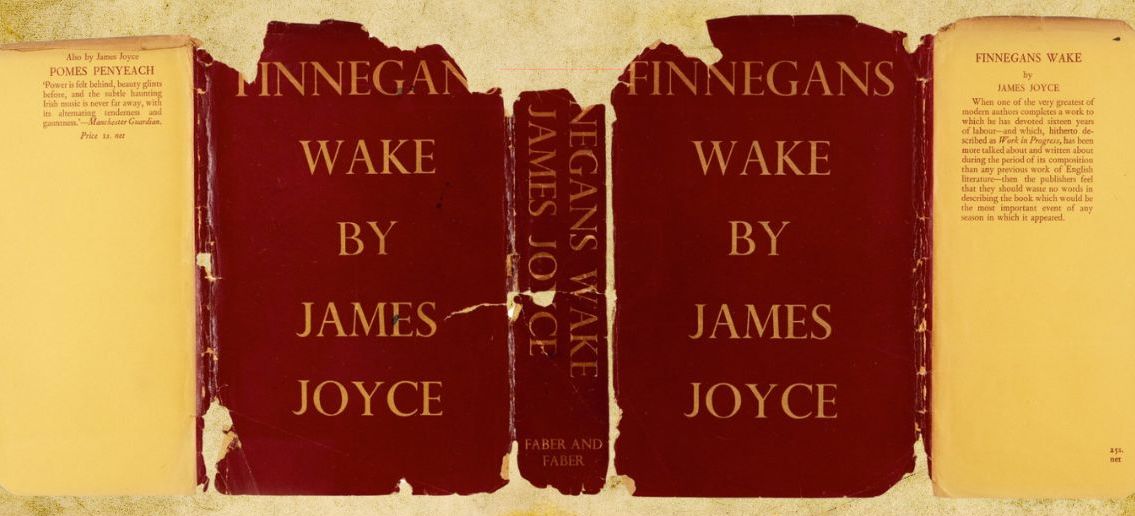

In early 2011, during one of my band’s last tours, I decided to read Finnegans Wake in our tour van. I’d taken a course on Ulysses in college, so I knew this would be no easy feat, and I brought along several bulky guides (including the six-hundred-page Annotations) to help me decipher Joyce’s cryptic masterpiece.

Reading Finnegans Wake will be good for you, I told myself. You won’t just write song lyrics about your anxieties all day. You can reconnect to literature on the road!

I’d come close to a nervous collapse on our previous tour—my bandmates fighting, our gear breaking down, our nights spent packed into a single motel room, our meals a grim parade of Subway foot-longs—and the life that had seemed like a dream in my early twenties, a Kerouacian adventure, now felt like a mental health crisis as I neared twenty-seven.

My band, the Boston group New Collisions, was finding more and more success (we’d recently toured with The B-52s and opened for Blondie, two inventors of our New Wave-inspired sound), but I wasn’t built for the endless travel, the emotional highs and lows of nightly performance, or the time away from my writing desk, where I was always happiest.

This tour will be different, I assured myself. You’ll be in dear dirty Dublin with Joyce. You won’t fixate on your fears, your fading youth.

From the start, it was a disaster. Synth rock blared in the van as I stared at the Wake’s perplexing language, and every time (with help from the guides) I came close to grasping a sentence like, “Phall if you but will, rise you must: and none so soon either shall the pharce for the nonce come to a setdown secular phoenish,” we arrived at the venue for load out and soundcheck. The next morning I’d be back in the van, squinting at “Phall if you but will” as I gulped down gas station coffee.

Though I’d co-founded New Collisions and written most of our songs, I was at core a bookish introvert with no business on a club stage every night

In a way, that tour was a microcosm of my band years. Though I’d co-founded New Collisions and written most of our songs, I was at core a bookish introvert with no business on a club stage every night. Nor was I ever that impressed with my own songwriting, which, while well received, felt stuck inside in a solipsistic loop. (Our most popular song, “Dying Alone,” was a perfect example of this).

I felt more at home writing fiction, where I could create a cast of characters who faced the challenges of their society, not just obsess about my middle-class neuroses. When I left the band a few months later to focus on fiction writing, I never looked back.

*

More than ten years passed. In late 2022, I was sitting at my desk one morning, working on edits of my first novel, Plastic, which had recently sold to Pantheon Books. Set in a world of plastic figurines, the book tells the story of a plastic woman named Erin, who struggles through a future of climate crisis and widespread eco-terrorism.

I was editing an early scene, where Erin visits a funeral home in this violent future, riding a moving walkway past the dozens of viewing rooms inside the complex. Then, to my surprise, something unexpected happened: a spotlight shone down on Erin and she started to sing about her grief, accompanied by music that played from the air around her.

In the hallway of the funeral home, holograms of the dead stood outside the viewing room doors, smiling in eerie silence at the mourners. Now these holograms sprang to sudden life with the music, then partnered off and waltzed down the hall, belting the oohs and aahs of backup vocals. They only shuffled back to their doors when the song was over.

I sat at my desk, startled and uncertain, but also intrigued. Though I hadn’t planned it, my book now had a full-on musical number, like a sequence from My Fair Lady or Crazy Ex-Girlfriend. I could even hear the melody line in my mind. For over ten years, I hadn’t written any song lyrics, had barely touched a guitar.

But I’d adored musicals all my life—everything from Duck Soup to Sweeney Todd to Dancer in the Dark—and I could envision musical numbers throughout Plastic: the figurines launching into song, the surreal dance routines in the background. Soon I was putting off my other edits to scribble stanzas late at night.

I sent these scenes to my editor, the brilliant Anna Kaufman, and gave her full veto power over the idea. I admitted I’d been working long hours, that I might be getting a bit batty at my desk. But her response came back quickly: “This is AMAZING.”

After that, I thought of Plastic as a musical, and welcomed back the lyric writing of my past. It wasn’t long before another thought occurred to me: there could be music for these lyrics, a Plastic concept album, a cycle of songs that told the novel’s story.

*

This January, I sat listening to the final masters of Plastic: The Album. What had begun as an idle thought had become a year and more of absorbing work, a collaboration with the artist Cindertalk and the singer Stranger Cat. The album begins with Erin in isolation, mourning the death of her father; continues to her romance with a blind figurine named Jacob; then leads into her conflicts with her terrorist sister, Fiona, who resurfaces after many years in hiding. (The song about Fiona became the album’s first single).

As I listened, I understood why I’d never truly loved my old songs: the lack of storytelling in my work, a novelistic dimension to compel me. Back then I’d written about my thoughts and feelings, but there was never a larger story to tell, never a character to explore beside myself. With Plastic, each new song contributed to the story, giving the album the same emotional arcs as the novel. The songs delved into Erin’s feelings, matched sounds to her emotions, but also conveyed the unfolding action of her life.

Back then I’d written about my thoughts and feelings, but there was never a larger story to tell, never a character to explore beside myself. With Plastic, each new song contributed to the story, giving the album the same emotional arcs as the novel.

In high school, I’d often skip lunch and use the money to buy old records, leafing through vinyl jackets in the record store near my house, the now-defunct Integrity ‘N Music. Five dollars could buy me a classic LP, anything from Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On to Joni Mitchell’s Blue to The Kinks’s Arthur. The jackets were scuffed and the vinyl scratched, but the music came through warm and full when I’d sit on my bedroom carpet later that night, staring at the pictures in the gatefold, lost in the world the songs created.

Those albums were immersive experiences, novelistic at their core, guiding you through a distinct journey from song to song. They are often called “concept albums,” and perhaps all the best albums are concept albums in some way, with a deep unity to the listening experience.

I can’t compare my own work to these classic records. But, after all the angst of my twenties, it’s a joy to at last make music that feels bigger than myself. And I owe it all to singing figurines.

______________________________

Plastic by Scott Guild is available via Pantheon.

Scott Guild

Scott Guild is the author of Plastic. Guild received his MFA from the New Writers Project at the University of Texas at Austin, and his PhD in English from the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. He served for years as assistant director of Pen City Writers, a prison writing initiative for incarcerated students. He is currently an assistant professor at Marian University in Indianapolis, where he teaches literature and creative writing. Before his degrees, Scott was the songwriter and lead guitarist for the new wave band New Collisions, which toured with the B-52s and opened for Blondie.